In 2011 I presented an attempt at a comparison of portals for legal history. Last week I spotted a new online guide to legal history at CLIO Online which definitely does not offer a portal, but instead it has so many qualities that I am very happy to present it here. CLIO online is a German history portal with several subdomains. This portal is partially available in German and English, and it is also connected to websites such as H-Soz-Kult and arthist.net. The current guide, created by Andreas Wagner, is in German, but the bibliography and the additional commented web directory can certainly be most helpful. In this post I will introduce you to the main sections and highlight a number of its qualities. In my view this guide wets the appetite for more, starting with a version in English.

From legal history to digital legal history

Let’s first introduce here Andreas Wagner, the author of the new Clio-Guide Rechtsgechichte. Wagner studied philosophy, sociology and information science. He became a specialist in the field of the history of Early Modern international law. Since 2013 he works at the Akademie der Wissenschaften und Kunste in Mainz with a focus on the research project for the School of Salamanca. Legal historians will know him also for his work in the field of digital humanities at the Max-Planck-Institut für Rechtsgeschichte und Rechtstheorie in Frankfurt am Main since 2017. With colleagues at Frankfurt am Main he organized in 2021 an international online conference on digital legal history with the nicjname DLH 2021, reported also here.

On May 2, 2024, the institute in Frankfurt alerted at X/Twitter to the new online Clio guide. These guides rightly deserve their own subdomain at the CLIO portal. The guides are divided into five main groups. Apart from themes with particular historical genres thers are sections for epochs, regions and countries, collection genres, and a section for Arbeitsformen und -techniken, to be understood as digital methods and techniques. The range and coverage of this fleet of guides is impressive, as is the number of new guides in preparation. Interestingly, the first general guide for history of the CLIO portal (2016) is still available. Its presence shows the long road taken in a few years.

The new guide scores immediately with its clear division into sections, the presence of a PDF version (41 pages) and a separate commented web directory (Linkliste). The first section is a real tour de force, a combination of an introduction into the current state of (digital) legal history, the use of digital methods and techniques for legal history, and its relation to related disciplines. The second and largest section focuses on the contributions of scholars and projects divided into six sections. Institutions and publications each get their own paragraph. A chronological select bibliography (pp. 28-41) on the use of computers and the role of digitization in legal history since the 1970’s follows; there are five sections: before 1990, 1990-2000, 2000-2010, 2011-2015, and from 2016 onwards. The endnotes of the web version appear as footnotes in the PDF.

A rich guide

Wagner starts his guide sketching skillfully some developments leading to the current position of legal history and the role of digital humanities. Legal history does not exist in vitro. In many countries legal history is closely connected with contemporary law. Sometimes this leads to a position for legal history as a mere handmaiden for the study and practice of contemporary law. In particular other disciplines, such as the social sciences, economics, history and philology influence the use of computers and the impact of digital methods. Wagner notes a number of matters implying legal history cannot indiscriminately take over methods, approaches and tools from other disciplines. My brief summary cannot do justice to this thought provoking conicse introduction

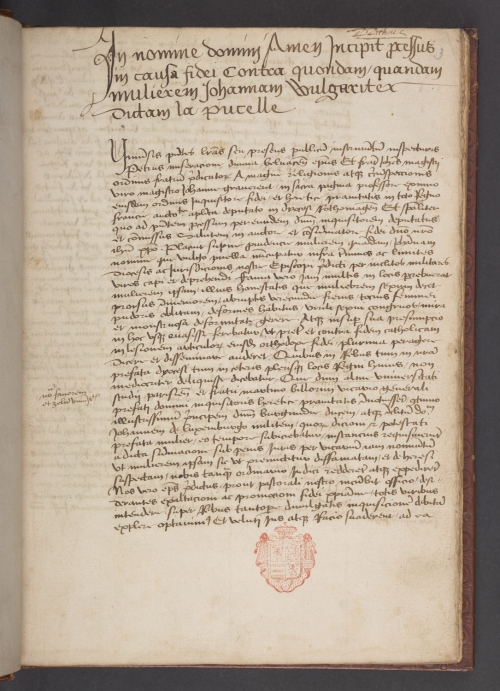

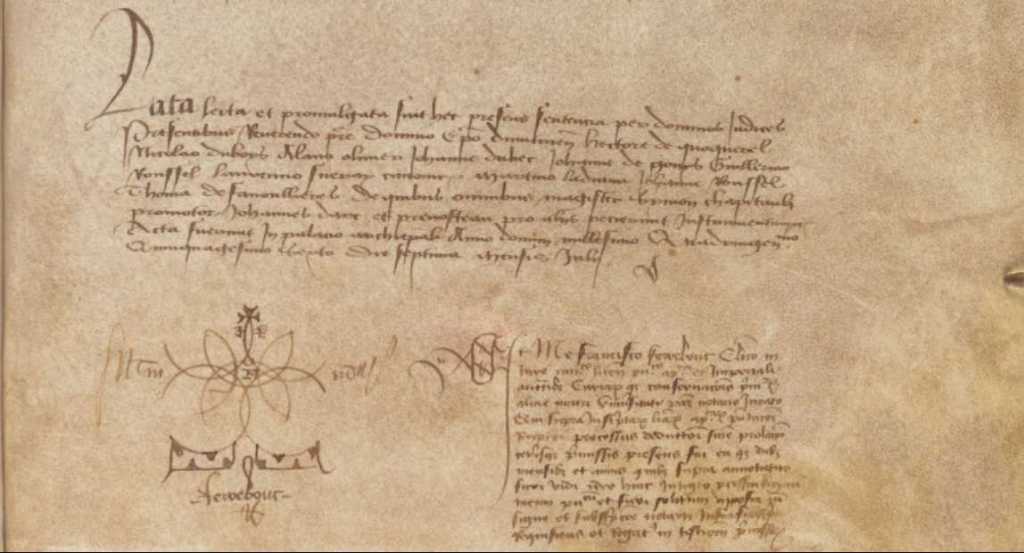

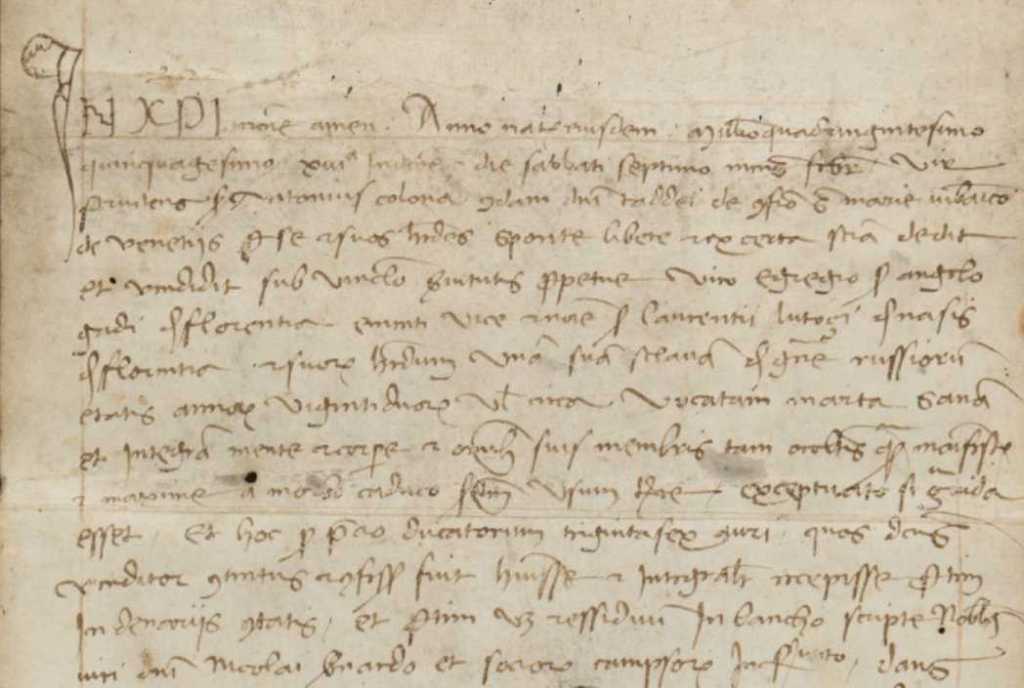

The core of Wagner’s guide is the discussion of initiatives divided into six sections, dealing with court records, law collections, linguistic resources, methods and digital collections, commercial databases and in the last section supporting resources created and maintained by a number of scholars. In particular the first section brings you not just to a number of research projects dealing with the history of some important supreme courts in various European countries, it shows you the early preponderancy of large teams using computers to assist their projects and to bring data eventually online. This part of early digital legal history deserves attention.

The subsection on law collections focuses on the history of the work done in Linz to create a searchable database with all sources for classical Roman law. The project history with various forms and conversions is heroic. Wagner is right in noticing the version now available in open access offered by Amanuensis excludes the footnotes and introductions of the full printed editions, but nevertheless it is in my view most helpful for quick orientation. The app version is not mentioned. I discussed Amanuensis and other online collections for Roman law in an earlier post (2015). In my view the addition of another example would strengthen this section.

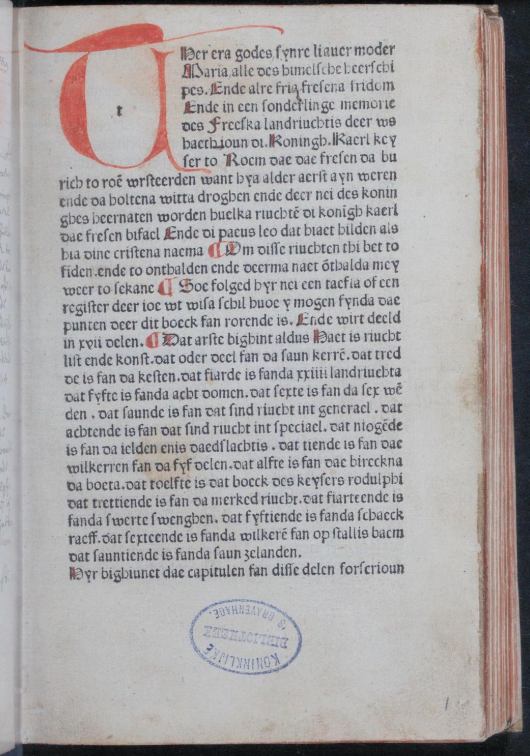

The third and rather brief subsection deals with linguistic resources developed around sources for legal history. The Deutsches Rechtswörterbuch gets most attention, but Wagner also points to linguistic databases for the records of the Old Bailey, medieval Scandinavian laws and a text corpus for contemporary German law. Some linguistic resources focusing on selected periods exist also for Flemish and Dutch legal history.

The move from digital collections on CD-ROMs to online collections as we know them today is the main thread in the fourth subsection on digital methods and digital collections. Examples from Germany and Switzerland illustrate this section. In the fifth paragraph Wagner looks at commercial legal databases. Each country has a number of online databases offered by major publishing companies. Wagner points at some of the initiatives to create similar databases in open access. Some commercial firms offer also historical collections in open access.

I was a bit surprised to find my name in the final subsection about supporting resources for legal history, and this in the company of Mary Dudziak and Andreas Thier. Mary Dudziak’s name is associated with the Legal History Blog which truly deserves its name and fame, and also with the yearly digital history prize of the American Society for Legal History. My legal history website and blog offer indeed some support. I suppose I am just too much aware of the subjects and themes not or seldom mentioned or treated from just one perspective. However, I am happy to bring some online assistance, in particular alerting to relevant (new) online resources, and presenting my impressions of them.

In the third main section of the guide Wagner looks at a number of German and American institutions and societies for legal history. He mentions a number of research centers, not forgetting his own Max-Planck-Institut or the Stephan-Kuttner-institute for Medieval Canon Law. The fourth section focuses on publications in the field of (digital) legal history. Wagner restricts himself to a small number of journals. Some journals for legal history devoted specials to digital legal history. In 2022 the Journal for Digital Legal History was launched at Ghent University. He reminds us also of the online conference on digital legal history held in 2021.

Bibiiographies and links

At some points in this post I felt an itch to add information that seemed to be missing in the various sections of Wagner’s guide. However, the information presented in the footnotes is already rich with references to scholarly literature and online projects. The possible importance and uefulness of adding here some information is also diminished by the presence of a very substantial web directory. Online bibliographies stand at its start, and this is very much a key element for its value. At Zotero Andreas Wagner has created with other scholars an online bibliography on various aspects of doing digital legal history and the use of digital humanities. If you think something is missing in it, the best thing to do is to consider becoming a contributor to it yourself.

Creating a sensible division for any list is often a challenge. This web directory has eight sections, featuring for instance a fair number of online journals for legal history. You might quibble about the position of a particular resource or even about the order of presentation of resources, but you will be helped very much by the concise descriptions of the resources. More often you will readily admit you encounter soemthing new and relevant for your own interests. Omissions are not be frowned upon or deplored. You had better bring your suggestions simply to the attention of Andreas Wagner and the CLIO team. In the end this guide is not a portal promising you eveything possible. I can assure you I encountered here enough unfamiliar projects and links, although Germany and the United States figure indeed large.

Food for thought and reflection

In his final remarks Wagner notes a clear difference between the appearance of digital legal history in publications on one hand, and the daily use of digital collections, pnline databases, online preprints and digital versions ofmscholarly literature. He signals also that legal history will probably turn more to philology and linguistics than to the spocial sciences when applying digital methods. Wagner stresses the need for a careful use of text mining in order to prevent hasty and sloppy conclusions from legal materials that cannot be approached as an ordinary linguistic corpora. Those who doubt this statement should perhaps look at my latest post about the various possible interpretations of the supposed proverb about the judge who does or does not calculate.

To me the warnings about the difficulties of text mining for legal history sound familiar. Surprisingly Wagner does not mention Jo Guldi and her recent book The dangerous art of text mining. A methodology for digital history (Cambridge, etc., 2023). Guldi clearly inspired Wagner to give space in his guide to institutional foundations for (digital) legal history, a matter she advocated powerfully at the 2021 online DLH conference. By the way, Jo Guldi recently told Anaclet Pons in an illuminating interview on historical methods and digital research at Politika about her road to digital history after a start as a scholar of classical languages and about the challenges she met and meets in doing the digital research she deems important.

I am not advocating a kind of Methodenfreudigkeit, a kind of wallowing in thinking and talking about methods, but there is a clear need to be aware digital legal history forms a new threefold discipline. Each of the three terms in this compound word, digital legal history, calls for reflection. Recently I made some critical remarks about a project in spatial history, not because it was spatial history, but due to some shortcomings in proper historical research.

In 2016 I looked at Lara Putnam’s by now classic article in the American Historical Review on the digital turn in (global) history. She, too, stressed the need for reflection about the use of digital tools and methods. Without sufficient appreciation of their impact you will not notice how the kind of history you do and preach, your own way with the digital turn, actually changes or will change. Putnam pointed out the pioneers of digital history were very critical about their own approach, methods and tools. We should not be tempted to think you can now apply any branch of digital humanities in blissfull ignorance of possible and actual biases, pitfalls or failures.

Let one example of sensible use of a well-known digital tool suffice: In Zotero you can substantially enhance bibliographies and other lists by adding judiciously tags to items. If you help to strengthen the Zotero bibliography for digital legal history by joining the support group, or when you enrich the commented links list for this discipline now online at the CLIO portal with better tags or descriptions, users can get better search results for the things they want to study or use.

Andreas Wagner is to be applauded for his sustained efforts for not just doing digital legal history, but more particular for his continued support for building and shaping its infrastructure and helping shcolars to reflect about the way legal historians can use and adapt digital humanities in sensible and reliable ways. His guide is a milestone on the roads of digital legal history, not in the least for showing also key developments in thid discipline. May it inspire you to find the courage to admit wrong turns, dead ends and partial auccess in your digital research for legal history! In my view this guide can certainly help you to sharpen your senses for balancing the needs of critical research, legal thinking and practice, and sound historical research. Tn my view digital legal history in its most valouable form can offer not only answers but will also bring new questions and perspectives on law and justice in past and the present. Doing digital legal history is not a matter of easy linear progress and success. Wagner invites us to take enough time for reflection on the theories and views that influence our perspectives and practice as legal historians.