Transporting goods by ship is a risky business, certainly without modern forms of insurance. In the Early Modern period European merchants, sailors and traders developed a number of ways to mitigate the costs of damage at sea. In the European project Average-Transaction Costs and Risk Management during the First Globalization (Sixteenth-Eighteenth Centuries) (AveTransRisk) of the Centre for Maritime Historical Studies at the University of Exeter one particular solution comes into view. Interestingly, aspects of legal history come very much into view within this project with maritime history as its core. One of the many results of this project came unexpectedly for me into view, thus bringing a welcome chance to present it here and to look at some of its aspects.

An international project

The ERC-funded project AveTransRisk is led by Maria Fusaro, director of the centre in Exeter and also leader for the other major project of the centre, Sailing into modernity. The project aims at gaining insight into legal institutions helping to divide among parties the risks of costs due to damage during a voyage at sea. As a means to achieve this objective the legal construction of general average forms the focal point of the historical investigation of the large project team. For this project data were collected for the period 1500-1800 from five countries with a large shipping trade: England, France, Italy, the Low Countries and Spain.

A major result of this project is a database accompanied by a glossary and introductions to the source materials. These introductions come with examples of voyages and a filter to select these voyages directly. For Italy sources from Genoa and Tuscany are used. Pisa and Livorno are the two Tuscan ports in this section. The inclusion of Malta is most welcome, even though in this case the nineteenth century is the research period. For France the focus is on the Royal Insurance Chamber, in existence between 1668 and 1689. In the case of Spain the main source of information for this projet is the Casa de la Contratación in Seville. I will discuss some of the example voyages, but I encourage you to investigate these introductions and examples yourself.

Alas currently similar introductions for the two main ports of the Low Countries in the Early Modern period are not yet present, nor have data been entered into the current version of the database, and the same is the case for England. For Antwerp I cannot give you quick guidance except pointing you to the Felixarchief, and to publications by two members of the Exeter team, Gijs Dreijer and Dave de ruysscher. At my blog I discussed in 2014 a number of Dutch and Flemish examples of municipal courts led by aldermen, among them the schepenen of Amsterdam dealing with “Assurantiën, Averijen en Zeezaken” and the resources at the Stadsarchief Amsterdam for studying this tribunal. Luckily, this archive explains itself – only in Dutch – the nature of the averijgrossen for the period 1700-1810 in its holdings, with illustrations, references to other relevant archival records and resoiurces such as digitized newspapers, and examples of some cases. Some 10,000 cases can be searched online using an index leading you directly also to scans of the acts. This is a major difference with the situation in 2013 at the launch of this index. I suppose this information concerning Amsterdam will in some form appear eventually also at the website of the project in Exeter.

In happy cooperation Gijs Dreijer and I contributed an article about an Early Modern legal treatise on average by Quintyn Weytsen to a volume about important Dutch legal works since 1500, ‘Een tractaet van avarien – 1617 – Quintyn Weytsen (1517-1564)’, in: Juristen die schreven en bleven. Nederlandstalige rechtsgeleerde klassiekers, G. Martyn, L. Berkvens and P. Brood (eds.) (Hilversum 2020) 38-41 (also online, Pro Memorie 21/1 (2019) (PDF)). Weytsen’s treatise was often reprinted. In Amsterdam the Kamer van Assurantie en Averij referred to it, and it influenced also customary law in Antwerp. We had liked to add to our article an image of the impressive painting shown here above, but this was not possible, hence my choice here.

Using the AveTransRisk database

It is time to look more closely at the database. Of course there is at the start an example of the way general average was calculated. The vessel, the freight and cargo were all taken into consideration. It helps you to see how costs for damage would become substantially lower than without this legal precaution. The general free search mode of the database allows fuzzy search results. The advanced search mode helps you greatly for many kinds of questions. You can add and remove text fields and choice fields at will. With a choice filed you can select from a dropdown menu with a wide range of categories, and also restrict your search to one or more archives.

The range of fields to choose from is truly luxurious. The advanced search guide does lists and explains the various field types. You can check for particular weather conditions, and for all kind of measures. This helps you also to refine or reframe your own research aims. The guide indicates you can only enter for French records the insurance date, and only for Spanish records the trials section is available. Some of the query results, the ports involved and the events during a voyage can be shown also on a map. You can copy and print your results, or export them as a CSV file, Excel or PDF.

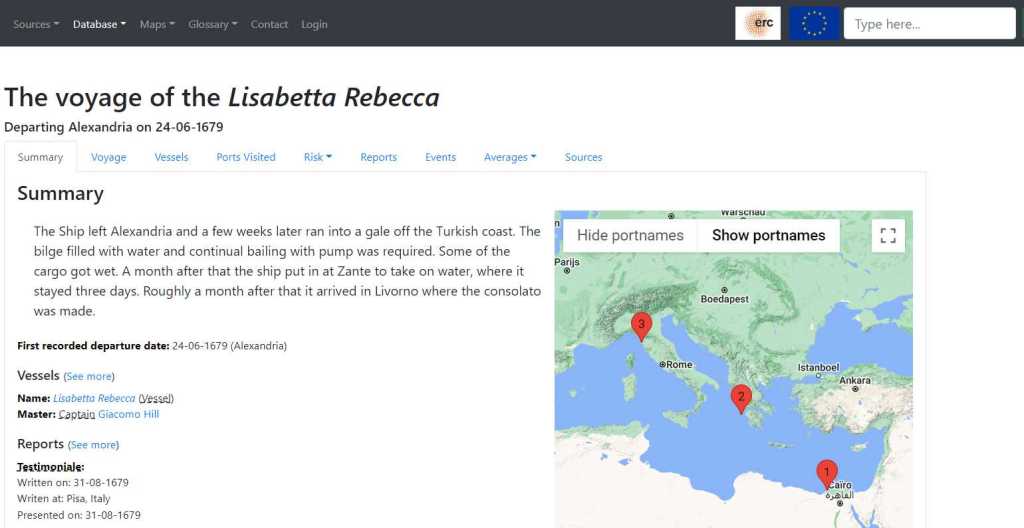

The database offers also six main list overviews: for averages, events, voyages, vessels, masters, and reports. When you select for example in the ports view Dunkerque you get an overview of all voyages mentioning this harbour town long feared by sailors and traders for its pirates. In my opinion it is a good idea to familiarise yourself with the database by using first these lists, and to check at will the information about the voyages in the results. The screenprint here above shows a part of the summary for voyage no. 10016 created from two archival records held at the Archivio di Stato di Pisa. The database allow you to distinguish between ports visited, ports of departure and ports of destination. The locations can be chosen from a dropdown menu, hinting at the obvious need to standardize the names of locations in different languages. For other aspects, too, you can choose the aspect you want to focus on. The maps help you to visualise the voyages and to consider the amount of time a voyage and its aftermath took. The glossary and the table on silver equivalence in currency are most useful, too.

Early Modern shipping news

It is seducing to look at further aspects of this rich database, even when you might have wanted to find now also English, Dutch and Flemish voyages and cases. Of course ports in England, Flanders and the Dutch Republic do figure now, too, in the database. The new thing to highlight in the data available here is the combination of economic, maritime and legal history which mutually enrich each other. It throws new light on Early Modern transport.

The examples adduced as sample data deserve our attention here. Among the example cases for Genoese records is the story of a ship in 1639 first colliding with another vessel while loading (!) and suffering damage by storms at sea (voyage 502297). For cases from Seville just one example is adduced of a voyage in 1585 with damage to the hull of the ship, jettisoned mechandise and angry merchants in court who did not believe the crew’s story (voyage 70011). Here I had expected an example showing one of the typical Spanish flotas, the fleets so typical of Spanish naval voyages. There is a wide range of examples from Tuscany. The Antwerp vessel Corvo Volante – I guess originally named something like the Vlieghende Raef – sailing in 1599 from Brasil with sugar destined for Lisbon had to jettison some of its cargo off the Azores and ended its voyage in Livorno (voyage 10022). A French example adduced by the team cannot be missed here. They mention a voyage in 1670 (no. 92799) from Le Havre to Guinea, hence to the Americas and back to Le Havre, a typical triangle voyage well known in the Transatlantic slave trade, with indeed enslaved persons as its merchandise.

The rich documentation assembled within the database has led the team to a fair stream of publications. The archival background is duly mentioned in the section on datasets. Let’s certainly not forget the fleet of other resources for maritime history brought together by the research centre in Exeter at its website. The guide to naval records in the National Archives, Kew (384 pp., PDF) and its introduction by the centre take for me the palm as something absolutely worth saving whatever your views of the project on general average and its European legal history. The project finally came to my attention again thanks to the transcription model four team members contributed to the Transkribus project for Italian administrative hands (1550-1700), one of just four Italian models now available. As for the Dutch side of these project, it is good to know Sabine Go (Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam) leads hetrself in Amstedam the project Risky Business with Giovanni Ceccarelli and Antonio Iodice in her staff, Maria Fusaro on the advisory board, and some other members of the Exeter team (Dave de ruysscher, Guido Rossi and Lewis Wade) in its wider network.

The interplay between the economy, maritime trade, state regulations and city tribunals are at the heart of the AveTransRisk project. Legal historians can hardly complain about the efforts done here to bring general average into the limelight. The assessment of risks and the calculation of damages shed light on a very real aspect of Early Modern trade and commerce. This project is a contribution to comparative (legal) history helping you to compare for instance between city states and centrally governed countries. They bring the necessary details needed to confirm larger hypotheses in a more sophisticated way. Even now without the records from England, Flanders and the Low Countries the database is most valuable.

I will not hide my vivid interest in the very realistic stories told by people about their sometimes dramatic voyages at sea, or even suffering damage already on loading. They bridge the gap between legal abstractions and court narratives. It is great to have so many archival records now accessible online for anyone wanting to gain insight into general average as a matter of more than average interest for Early Modern and legal historians.

A postscript

You can now learn more about general average and the AveTransRisk project from the volume General Average and Risk Management in Medieval and Early Modern Maritime Business, edited by Maria Fusaro, Andrea Abboddati and Luisa Piccinno (2023), also available online in open access. Also available in open access is a special issue of the Quaderni storici 3 (2022) on risk management and jurisdictional boundaries in pre-modern Europe, edited by Maria Fusaro.