Sometimes real or supposed barriers keep you from investigating new subjects. For a long period I saw the sources of Byzantine law as a conglomerate of difficultly accessible sources. On my legal history website Rechtshistorie I scarely mentioned Byzantium and its laws, and to be honest, I was not always aware of this substantial omission. Nowadays algorithms tend to lead your focus to themes and issues, but this time a personal announcement about a new introduction to Byzantine law finally pushed me into adding some lines and references to my webpage on Roman law. On top of that came the question to look again for modern translations of the several components of the Justinian compilation. In this post I will tell you briefly about this new handbook and modern ways to approach Byzantine legal history.

Changing perspectives

When I started studying legal history in the early eighties of the last century three fields captured my attention: Roman law, medieval (canon) law and Old Dutch Law. Only gradually other fields such as the common law came into view, partially guided or seduced by the open stacks of the former law library at the Janskerkhof in Utrecht, a place often mentioned here. For my dissertation the medieval ius commune and its development during the Early Modern period became central in my research. When I looked at the study of the Justinian Digest Byzantine law at last came more into my view, thanks also to the projects of other researchers. At some point I detected the handbook by N. van der Wal and J.H.A. Lokin, Historiae graeco-romani iuris delineatio. Les sources du droit byzantin de 300 à 1453 (Groningen 1985). A month spent in Frankfurt am Main also meant literally coming a bit closer to current research on Byzantine law.

The history of the Byzantine empire or East Roman Empire spans a millennium. and somehow this period remained long at a distance for me, and I guess for many others, too. Judith Herrin’s classic work Byzantium (2007) did reach my bookshelves, but even though she devoted a short chapter to Byzantine legal history I was not pushed into action to update my website. This month I was surprised to reread a brief post from 2010 on my blog with some useful information about Byzantium and its legal sources. At Wikipedia you can now find articles on Byzantine law in various languages, often presenting in some detail the historical development of laws and legislation, but their sections on primary legal sources are often very succinct.

Thanks to Daphne Penna and her kind message last December I looked at the book she published with Roos Meijering, A sourcebook on Byzantine law. Illustrating Byzantine law through the sources (Leiden-Boston 2022). This introduction is also available online, with full access for private and institutional buyers, but with a bibliography in open access. The book of Meijering and Penna is more than just an anthology of well-chosen substantial and representative examples of sources for Byzantium’s legal history. The editors really want to make students and scholars first and foremost enthusiast about Byzantine law. Thus their book is more than only a modern successor to H.J. Scheltema’s Florilegium iurisprudentiae Graeco-Romanae (Leiden 1950).

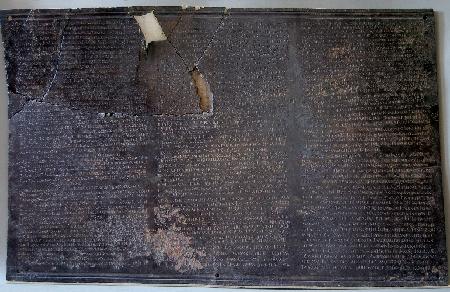

With Scheltema we see one of the truly great scholars dealing with the sources of Byzantine law. Together with D. Holwerda and N. van der Wal he succeeded in completing the massive new edition of the Basilicorum libri LX (17 vol., The Hague-Groningen 1955-1988). This edition gives both the text of the Basilica and the accompanying scholia (glosslike commentaries) in two separate series. The Dutch translation of the entire Corpus Iuris Civilis has just thirteen volumes.

Last year I did notice the Basilica Online, but my first visit was coloured by the perception this resource was only accessible for subscribers and subscribing institutions. I did not want to present it here or at my website as a stand-alone resource for Byzantine law with most of its parts out of reach for casual visitors. Luckily the new handbook acted as a nudge to look at it longer and better. Two important features of the Basilica Online are presented in open access, a bibliography by Th. van Bochove and a new praefatio by B.H. Stolte. If the new anthology with all its qualities does not yet convince you it is possible to find safe guidance to Byzantine legal history, these contributions by Van Bochove and Stolte should make you rethink your assumptions about this subject. Both authors do not hide the problems of their field, but their explanations and guiding remarks are illuminating. Stolte stresses the value of the Latin translation offered by Heimbach, and he notes the lack of an overview of the various tituli, some consequences of the separation between text and scholia, and the absence of the promised new Prolegomena in the Groningen edition of the Basilica. This edition depended very much on the use of microfilmed manuscripts, and some important manuscripts came only very late into view.

For my website the challenge was now to find a balance between redoing without any need the efforts for full introductions done by these scholars from Groningen or presenting a succinct but helpful series of commented references to major publications and editions, and assuring the result gives due attention to the work done by scholars working elsewhere, too. Daphne Penna convinced me quickly to present such information on my webpage for Roman law.

In my concise overview I mention in particular modern introductions. For the Basilica I point of course to the modern edition and its online presence, but I point also to a digitized version of the older edition by Heimbach and other German scholars. It seemed logical to create a section with some other sources available in modern editions, and I added references to online resources for finding Greek manuscripts and modern translations of Greek works.

Revisiting translations for Roman law

In January 2022 I assumed my overview of modern translations for Roman law was fairly complete, and thus I perhaps underestimated the value of the idea to provide more translations in European languages of Justinian’s Digest, the obvious aim of the project of Bela Pokol (Budapest) who invoked the help of DeepL to create translations into fifteen languages, In my post about his massive enterprise, aiming at contemporary lawyers and less at scholars of Roman law, I tried to establish the merits of DeepL’s translating capacities and to assess the value of Pokol’s translation which has the English translation by Samuel P. Scott as its starting point, not the Latin original. By the way, DeepL deals now with 29 languages, including Lithuanian, Ukrainian and Bahasa Indonesia, but there is no Latin.

By sheer coincidence Bela Pokol asked me last week to look again at the presence of completed translations for Justinian’s Digest in modern languages. Using resources such as Unesco’s Index Translationum and the Karlsruher Virtual Catalogue I noticed I had not yet added everything I had deemed necessary at my web page. Even the incomplete but most valuable German translation project which reached D. 34 in 2012 was missing. I checked also the library catalogue of the Max-Planck-Institut für Rechtsgeschichte und Rechtstheorie in Frankfurt am Main.

Eventually a second hunt for finding a digital version of the volumes of the Repertorium der Handschriften des byzantinischen Rechts led me inter alia to the French Pinakes portal for Greek manuscripts (IRHT, Paris-Orleans) which mentions among its links the databases of Princeton University Library for tracing digitized Greek manuscripts and modern translations of Byzantine sources. Both databases can be used with a filter for Law. Luckily at Pinakes the three volumes of the repertory for Byzantine legal manuscripts have been used. It seems the PDF’s of the repertory created by L. Burgmann, A. Schminck, D. Getov and other scholars are now absent at the server of the institute in Frankfurt; I could only retrieve them for the first and third volume. Many volumes of the Fontes Minores series edited in Frankfurt with articles and editions of legal texts are now available online in Göttingen.

You will agree with me that with a fair number of modern introductions in several languages, important online introductory essays and bibliographies in open access, a number of recent editions of legal texts, some of them with translation, and even online access to repertories for (digitized) manuscripts and translations, you can no longer deem Byzantine law completely out of your reach. I can imagine you might feel a bit dazzled by the efforts of eminent scholars! However, surely Penna and Meijering have done their utmost best to infect you with their enthusiasm to embark on your own journey into Byzantium’s legal history. An empire surviving more than one thousand years and covering in some periods large areas of Eastern Europe and Asia Minor deserves scholarly attention, in particular when you realize the Eastern Roman empire played a key role in transmitting the sources of the classical Roman lawyers.