On July 1, 1863 slavery was officially abolished in Suriname. A ten-year transitional period followed during which former slave owners received a monetary compensation for each former slave. Since many years people originally coming from Suriname celebrate in The Netherlands on July 1 the feast of Keti Koti, “The Breaking of the Chains”. It is only fitting that last week the digital version of slave registers kept between 1830 and 1863, now hold by the Nationaal Archief of Suriname (NAS) in Paramaribo, was launched by a number of institutions led by Coen van Galen at the Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen and Maurits Hassankhan at the Anton de Kom Universiteit van Suriname, with support from the Dutch National Archives in The Hague.

Last year I reported here on the project to move a number of archival collections concerning the history of Suriname from the Dutch Nationaal Archief to the NAS, and to digitize also a number of these collections. Collections with relevancy to legal history figure large among them. The digitization of the slavery registers is a key element completing the efforts for digital access and conservation, indexing the registers and making them much more accessible for researchers and the general public worldwide. In this post I will look at these registers and their online presence.

A crowdsourcing project

In January 2017 the project for indexation and digitization of these slavery registers started, just after the transfer of important archival collections from The Hague to Paramaribo. A campaign with the slogan Maak de Surinaamse slavenregister openbaar, “Make the Surinam slavery registers public”, proved effective. Some 600 people donated money for the project, and some 400 volunteers helped indexing the registers. To put the record straight, anyone could and can come to these archives to gain access to the original volumes, provided their material state is not too fragile. It is safe to assume that you need to come with good arguments to touch them now they can be consulted online. The Dutch National Archives did already provide public access. The operation to bring archival collections back to Suriname created a more urgent need for conservation and digitization.

In January 2017 the project for indexation and digitization of these slavery registers started, just after the transfer of important archival collections from The Hague to Paramaribo. A campaign with the slogan Maak de Surinaamse slavenregister openbaar, “Make the Surinam slavery registers public”, proved effective. Some 600 people donated money for the project, and some 400 volunteers helped indexing the registers. To put the record straight, anyone could and can come to these archives to gain access to the original volumes, provided their material state is not too fragile. It is safe to assume that you need to come with good arguments to touch them now they can be consulted online. The Dutch National Archives did already provide public access. The operation to bring archival collections back to Suriname created a more urgent need for conservation and digitization.

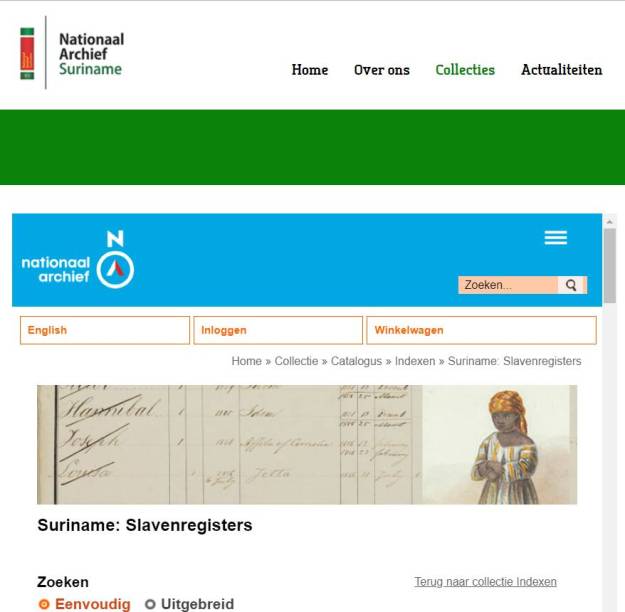

The digitized registers now in Paramaribo [NAS, toegang (finding aid) 16, inv.nrs. 1-43] can be accessed using an index form shown above. On purpose the NAS has not placed these registers among its forty digitized archival collections. The Dutch National Archives provide also online access to the slavery registers among its ever-growing set of online indexes. You can download the index in its entirety (4,2 MB, zipped file). At this point something becomes clear when you look at the URL of this file, a web address in The Netherlands at the search portal Ga het NA of the Nationaal Archief in The Hague. The search form of this digital resource at both archives is almost, but not completely identical.

Accessing the slavery registers

You can use either a simple search form (Eenvoudig zoeken) with three fields, one for a free text search and two fields for setting a period, or go to Uitgebreid (Advanced search) with more fields. In the second mode there are additional fields from the slave name, the name of the mother, and the name of the slave owner. You can click on the search results in order to get both the information on a person, including also gender, references to the registers and the type of register – with its inventory and page number – and an image of the page in question. It is possible to zoom in at will to any image. Each scan has an individual URL, a URL from my country when viewing individual results, meaning there is one single database behind the two versions. By clicking on the field name in the results you can change their order. You will find either the names of owners or the name of the plantation and its location.

It is not my purpose to single out here any defects and omissions, but a few things are very visible. First of all the version hosted in The Hague contains additional information which is not or not yet provided at the website of the NAS. The section Achtergrond (Background) informs you about the information given in the search fields, with a second page about slavery in Suriname and the introduction of slavery registers and their survival. There are important losses, not in the least some registers of slaves owned by the Dutch colonial government. In the registers mutations such as birth and death, acquisitions and sales should be written down. A third page on Gebruik (Use) contains instruction on the use of the indexes and the interpretation of results, and also a handy list of common abbreviations in the registers. The other pages contain a colophon about the project and the user license (CC-BY-SA 3.0 NL).

A second thing to note is the incomplete translations in the English version of the search form. Even the simple search form has not yet been translated completely. The field names in the results screen have not been translated. A much sillier thing becomes also visible: In cases where there is no gender information, the volunteers entered the word Leeg (Empty). I suppose there are more concise and effective ways to convey the fact that no data have been entered in a particular field.

Viewing the context

Using to a large extent at this moment only Dutch for this project is not a particular lucky thing, and you can even extend this to the project website. Translations in languages such as English and Sranantongo are not just welcome, they are simply needed to really open this resource to people worldwide with interest in Caribbean history, the history of slavery or Dutch colonial history. For any project on Dutch colonial history in the East Indies contemplating translations into English and/or Bahasa Indonesia is luckily a natural thing. The project team states flatly these registers are a worldwide unique resource, the only series of its kind. On the project website some further, rather important explanations about the actual state of the slavery registers are offered. It appears no general index to the series existed. Some registers could be consulted on microfiches, but without one or more indexes searching would mean wandering in a jungle without much hope for any results. The thing to note here is that only in 2017 the need for an index was perceived as sufficiently urgent to start a project to deal with this sorry situation. Earlier on having only severely hampered access seems not to have led to constructive action. Van Galen and Hassankhan rightly stress the importance of the slavery registers for not only genealogical research, but as a key resource to connect with the manumission registers, neighbourhood registers of the city Paramaribo and other sources for Suriname’s history during the nineteenth century. The historic context and the slavery registers can enrich the information contained in them in both directions.

Surely we need to thank Coen van Galen and Maurits Hassankhan and the army of volunteers who succeeded in getting their tasks completed in time. Van Galen and Hassankhan provide on the project website a very useful page with four PDF’s with information that should immediately be included on the websites of both versions of the online index. The project leaders provide a list with the names of plantations and other Dutch posts in 1834 (530 kB), a list with the names of free people in Paramaribo in 1846 (2,2 MB), both created by Huub van Helvoort, a list with first names of enslaved people on a number of plantations (70 kB), and even a list of letter forms, letter combinations and some Dutch words in nineteenth-century Dutch script (650 kB). It is good to see some basic historical skills are not forgotten! However, to my disbelief I did not find on the project website the URL of the index, not even after a few days… The slogan Open the slavery registers seems to have been at least temporarily forgotten by the web team. More down to earth, the current summer heat in my country, the gulf of enthusiasm about the launch, and the very end of the academic year created perfect excuses for forgetting to open literally the doors to the final results of the project also at the project website. The absence of news items from June and July 2018 is another indication for the sleeping state of the project website.

Such omissions and minor problems can be fixed quickly. I would urge anyone involved with this project to proceed as soon as possible with distributing lacking information to both versions and completing the translations. This succesful project well deserves this last effort to remove the barriers and chains which hindered easy access and practical use. The slavery registers of Suriname deserve interest from many corners.

A postscript

The uniqueness of these slave registers should be considered in the light of the presence of similar registers held at the Nationaal Archief Curaçao (005, Archief Koloniale Overheid, inventory 3, Hoofdambtenaar Arbeidszaken, inv.nos. 53-60 (slavery registers), and 005 Archief Koloniale Overheid, inventory 16.6, Burgerlijke Stand/Bevolking/Registratie, inv.nos 116-117 (emancipation registers). The eight slavery registers have 1070 folia). In August 2020 I reported here about digital access to these registers from Curaçao, and in that case, too, the Dutch Nationaal Archief provides access to them, and again in a slightly but significantly different way. Okke ten Hove righly commented that you should view slavery registers in connection with manumission registers and other resources.

De database Slavenregisters is complementair aan de databases Emancipatie (Ten Hove en Helstone) en Manumissies in Suriname, 1832-1863 (Ten Hove) die gehost worden door het Nationaal Archief en werden tussen rond 2000 en 2006 in bewaring gegeven aan het voornoemd archief. Veel mensen van slavenafkomst kunnen hun weg in deze slavenregisters alleen vinden met behulp van de twee databases hierboven genoemd. Anders is het zoeken naar een naald in een hooiberg die niet gevonden zal worden.