When creating an article or even a blog post creating a mind map can be most helpful. Using maps to represent information about legal history or historic events and developments with a legal dimension can help you to see legal history in a wider perspective. This month Klaus Graf kindly alerted me at Archivalia to a German project with legal maps, Rechtskarten, the fruit of a cooperation between nine legal historians at a number of German universities. They aim at presenting an atlas touching on both legal and cultural history. Its current dimensions are still modest, but in my view thsi project can inspire other scholars to use or create maps for legal history, too. Somehow this project escaped my attention earlier on…

A variety of maps

The navigation of Rechtskarten is fairly simple. You can use the tabs for maps, authors, keywords (Stichwortregister) and timelines (Zeittafeln). Currently only sixteen subjects are presented, but their numbering shows at least one hundred subjects are in preparation. Thus it seems you should not worry too much about the fact four out of sixteen themes deal with the twentieth century. The earliest item concerns the Kaufunger Wald, a royal wood since the eight century until the late eleventh centuy. In this item created by Wilhelm A. Eckhardt the maps shown are both modern and old. The section Orte (locations) brings you to an interactive map guiding you to its exact location in the north of the modern Bundesland Hessen, to the north east of Kassel.

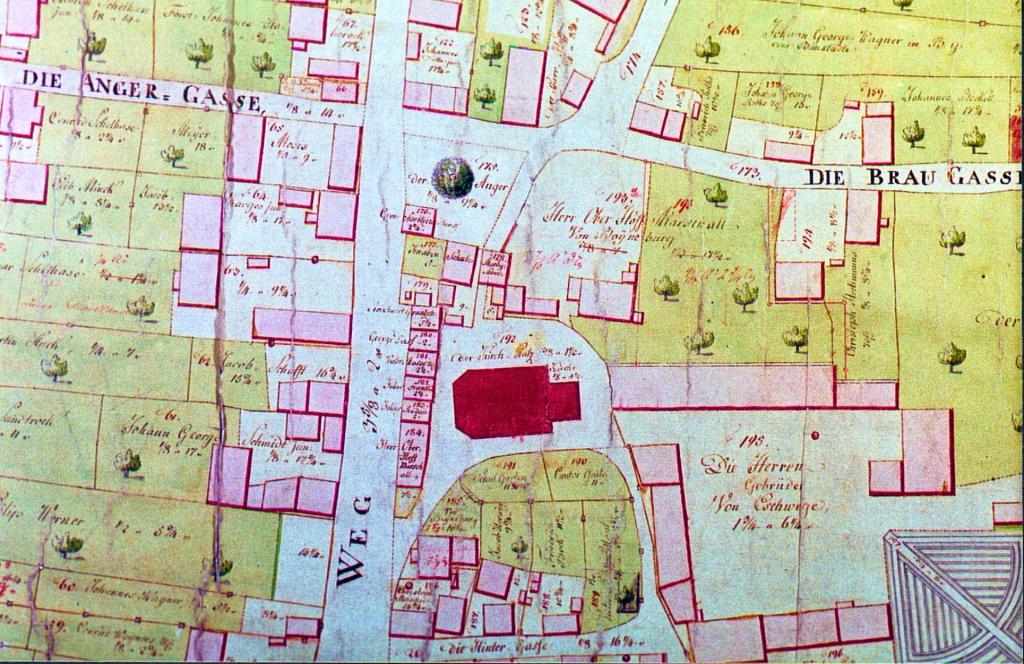

Wilhelm A. Eckhardt looks at legal iconography and legal ethnology in another contribution on village court locations in Hessen. Among the images is a photograph from the legal icongraphic collection of Karl Frölich held at and digitized by the Max-Planck-Institut für Rechtsgeschichte und Rechtstheorie in Frankfurt am Main. I discussed the background and possible use of this collection in an earlier post (2015). In that post I mentioned already the LAGIS portal for the regional history of Hessen with a section on these Gerichtstätten. Eckhardt righly mentions this in the bibliography to his article, with the latest item in it dating from 2013. The original land registry maps for Hessen (Urkataster) can be searched online at the LAGIS portal, too.

Among the items for the twentieth century i was a bit disappointed when I saw the media for the German Democratic Republic (1949-1990). I had expected some maps of the former DDR, but Hans Hattenhauer only added three diagrams touching the organization of this state, in itself surely enlightening and useful, but not the kind of map you would expect. In his contribution Hattenhauer concisely shows the low position of law and lawyers with the DDR. This item is in a way rather close to using a mind map. The visualisation of in this case state organization can be very telling.

Mapping some subjects has progressed clearly since the start of this project, somewhere between 2000 and 2015; information about the background and start of Rechtskarten is lacking, but Jörn Eckert died in 2006. The articles on the foundation of universities in the Holy Roman Empire (Armin Wolf) and the coming of printing to Europe (Jörg Wolff) share the same map, and it is instructive to compare the presence of universities with the advance of printing presses. The Atlas of Early Printing (University of Iowa) does a better job in many respects. You can easily add a layer showing university towns to the interactive map. The question about universities and early printing remains certainly valuable.

It is rather strange that the interesting article on maps of the Holy Roman Empire and the perception of minor states by Armin Wolf lacks any image of the maps under discussion. Is German copyright here the problem or have the Rechtskarten simply been abandonded at some point? Anyway, updating articles is in some cases clearly needed. The bibliography for the article by Jörg Wolff concerning the Tractatus de fluminibus seu Tyberiadis of Bartolus de Saxoferrato (1313/1314-1357) mentions only literature in German until 1999. By the way, this is one of the three subjects within this project not exclusively connected with German legal history. Armin Wolf’s contribution on the partitions of Poland in the eighteenth century as to some extent dynastic partitions lacks any map, image or location. The word Theatrum in the title of the work he discussed helped me to remember the project Welt und Wiissen auf der Bühne. Theatrum-Literatur der Frühen Neuzeit of the Herzog-August-Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel presented here in 2015.

Some musings

Sometimes things go differently than originally planned. Not every project succeeds, and though we all preach that you should learn from your faults and failures more often we hide them or try to forget about them. The Rechtskarten are in my view clearly an unfinished project, and not a failure. It is easy to point at shortcomings and omissions in this interesting pilot for a project with maps for legal history. I think the Rechtskarten can be revitalized. In fact it is a good exercise to come up with proposals for additions, corrections and updates. Some maps are now even only handwork. Only the articles on early printing and the foundation of universities belong to the field of cultural history. Many items lack a timetable, but the use of diagrams is an asset. The inclusion of some interactive maps is a sign this project certainly aimed – when feasible – at using modern tools. It would be great to have similar websites concerning subjects for other countries or regions, and I am sure you know some examples.

I had planned to open this year with other posts, but these I not have yet completed. Looking at an unfinished project with the potential to inspire others to create similar maps for their own field of interest seemed a wise thing to do!