Some subjects deserve highlighting in general within historical research. On several occasions I therefore present here contributions on major themes in legal history such as justice and injustice, slavery and discrimination. Women’s history, too, should figure here more often. It took me some time to look carefully at the results of a special digitization project finished earlier this year by the British Library. In March 2023 an overview of some ninety manuscripts was presented in a PDF, and in May a further overview was added for more than 200 newly digitized charters and 25 rolls. Adding these archival records greatly strenghtens this project by bringing even more depth and width. Charters and rolls appear here almost every year. In fact I had to restrict myself severely and to choose only some subjects and items touching upon legal history to make this post worth some of your reading time, and wet your appetite for more. Earlier on in fact I wrote here about digitized legal manuscripts of the British Library, and about the project with the Bibliothèque nationale de France for digitizing manuscripts created in England and France from the period 800 to 1200.

Making women visible

The first thing to note about the two sections of this digitisation project is that the British Library (BL) included also manuscripts and documents from the Renaissance, enlarging the period covered to the year 1600. On three occasions the BL’s Medieval Manuscripts blog alerted to the completion of the two series. On March 25, 2023 the overview for the manuscrips was presented, with a notice work on charters and rolls was nearly finished. The second post (May 11, 2023) announced the completion of the work on the rolls and charters. In the third post (May 21, 2023) not only links to the two PDF’s are given, but also to versions in Excel. It goes without saying these posts contain marvellous images for the digitized manuscripts, charters and rolls. For some women figuring in this project the BL created separate pages presenting their lives and the newly digitized materials concerning them.

Let me start with admitting that although I found it really difficult and even unfair to select here just some examples showing the wealth of materials newly digitised within this project I could not help delving deeper into the background of two manuscripts about a rather famous woman from the fifteenth century. As a matter of fact I concluded one manuscript really deserves mentioning, because it is not mentioned at one of the main websites about her.

However, I would like to start to look here first more in general at the digitized manuscripts stemming from and concerning medieval women. Most interestingly, you will find in the manuscript section also manuscripts which are actually archival records. This fact makes it more natural for the BL to add charters and rolls as a second section to this project. In order not to focus only on individual women I will look here first at some documentary genres. For this project the BL has digitized in this section four cartularies, three of them of monastic institutions, from Stixwould Priory (Add. 46701), Wilton Abbey (Harley 436), and Coldstream Priory in Scotland (Harley 6670), The fourth cartulary stems from John de Vaux and his daughter and co-heiress Petronilla de Narford (Stowe 776). There is a manuscript containing a census from St Mary Magdalene’s Abbey in Cologne (Add. 21072), and from this institution comes also a manuscript with revenues and expenses (Add. 21177).

Very much in a royal lineage are two wardrobe accounts, the first for Eleanor of Castile for the years1289 and 1290 (Add. 35294), including expenses for her funeral, and for Thomas of Brotherton and Edmund of Woodstock, sons of Edward I and Margaret of France (Add. 37656), although the last manuscript is clearly concerned with two men expending sometimes money for women at court. The manuscript with patents granted by king Henry VIII to Anne Boleyn stems from her period as marquess of Pembroke (1532-1533) (Harley 303). Another manuscript contains the receipts and expenses for the expedition bringing queen Margaret of Anjou to England in 1444 and 1445 (Add. 23938). The manuscript Royal 17 B XXVIII, compiled between 1536 and 1581, is a book of expenses of Princess Mary, containing also an inventory of her jewels, and a catalogue of printed books in the Royal Library. A bit more personal perhaps is a letter written on a single leaf by Mary, Queen of Scots, to Jacques Bochetel de la Forest, the French ambassador to queen Elizabeth I from 1568 (Add. 89480), preserved with an engraving showing Mary. To end this royal section I would like to mention the manuscript Stowe 784 with a Complainte sur la mort d’Anne de Bretagne followed by a discours on the mariage of Anne de Foix with king Ladislas of Hungary in 1514.

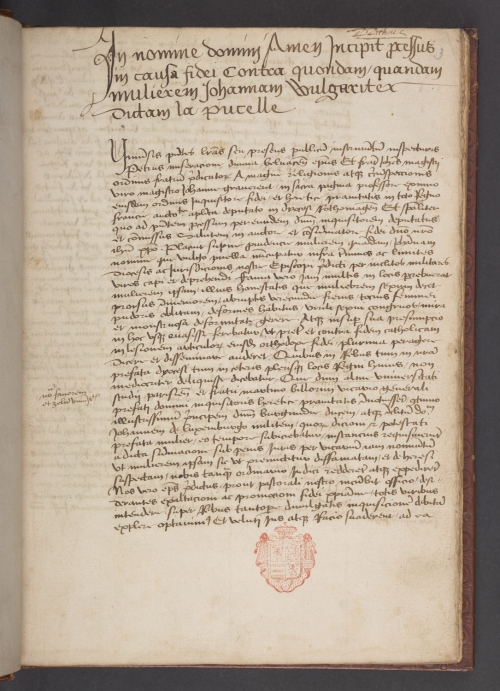

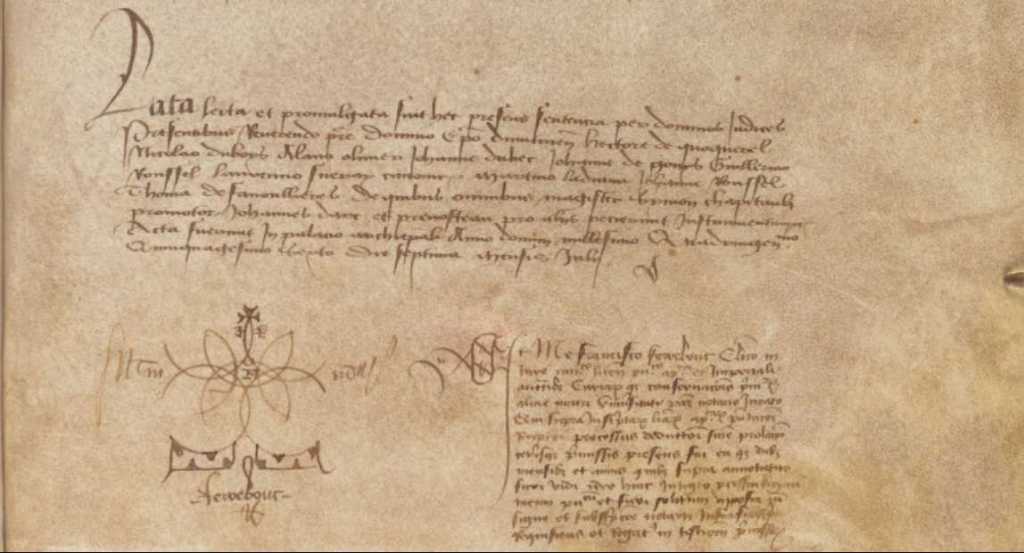

We arrive straight into legal history with the last two manuscripts I want to mention here. With my selection of fifteen items with a content more or less relevant for legal historians from a total of ninety digitized manuscripts the British Library certainly serves legal historians. Actually these two last manuscripts are quite famous examples of records of trials dominated by the use of medieval canon law. It is fair to say these manuscripts play a major royal in our knowledge about and perception of an iconic trial.

Those readers which read the caption under the first manuscript image in this post saw already the name Joan of Arc. The British Library digitized two manuscripts, Egerton 984, with the proceedings of the trial held in Rouen in 1431, written in the last quarter of the fifteenth and the beginning of the sixteenth century, and Stowe 84, an official copy of the proceedings of the rehabilitation trial in 1455-1456. At the portal Jeanne d’Arc the section on the trials tells you a lot about the manuscripts sources, editions and modern translations, but one of the manuscripts at the British Library, Egerton 984, once owned by Pierre Pithou, is somehow forgotten. It is tempting to provide you here with an overview of the manuscript tradition and modern editions, but this takes more space than I had expected. It is far more important to note the absence of any primary source for the interrogation held in Poitiers, the distance in time to the events of the manuscripts concerning the trial in 1431, and the closeness and official nature of the manuscripts concerning the second trial in 1455-1456, often called the rehabilitation or nullification trial. I created a PDF with an overview of the manuscripts and their digitized versions, and information about the most important editions.

Rolls and charters

The second section with digitized rolls and charters does bring you anyway a lot of legal documents featuring women in many capacities. The sheer number of some document genres prohibits their full selection here. There are for example 23 wills, 15 quitclaims (renunciations of right(s)), and nearly 90 grants. Eight rolls tell you about households, and nine chirographs have been digitized. Eight documents tell us about expenses for households. Seventeen documents concern medieval and sixteenth-century queens, and 27 documents mention a countess. It is definitively a challenge to show here women not only doing things they very obviously regularly could do and did, but also showing more exceptional cases, not forgetting to give a balanced view of social status and the origin of these archival records. With 200 charters and 25 rolls you are sure to find something touching your own personal or professional interests.

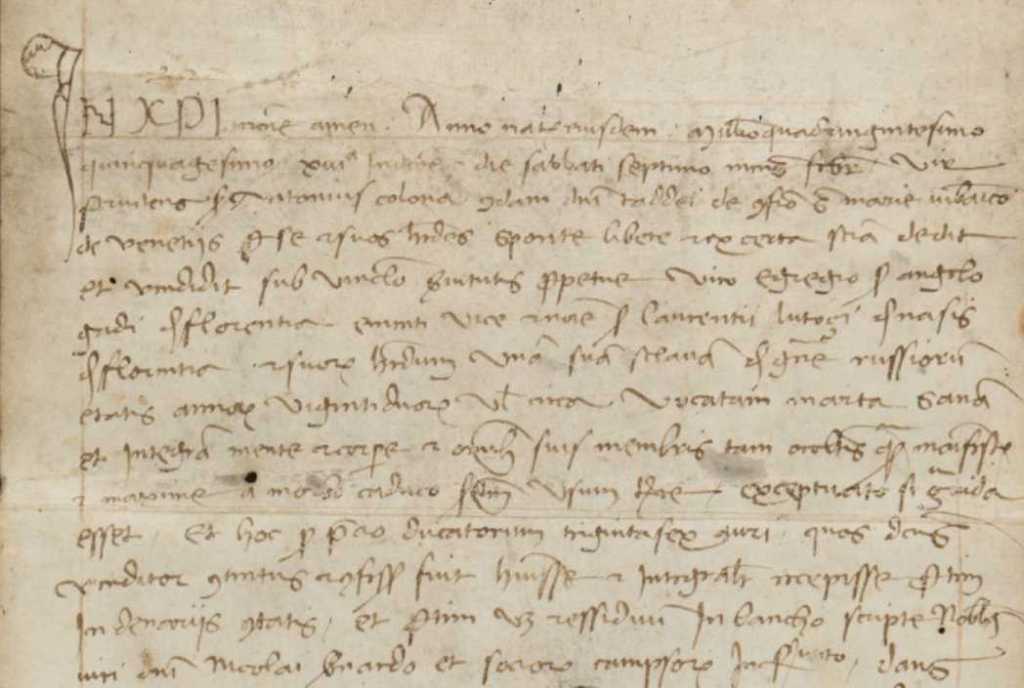

Many documents concern land transactions, but another attraction caught my attention. Add, Ch. 15340 is a notarial act recording the sale in 1450 by two Venetian men of an enslaved Russian woman named Marta to Angelo Gadi from Florence. Alas the act contains few details in the lines 7 to 9 about this sclava, who was 22 years old and healthy of body and mind.

There is a huge difference between this woman treated as an object for sale, a victim of slavery, and women founding institutions. Between 1237 and 1241 Ela, countess of Salisbury, founded Lacock Abbey (Add, Ch. 75578). Empress Matilda founded Bordesley Abbey between 1141-1142, overruling the original founder Waleran, count of Meulan who acted as a witness in this charter (Add. Ch. 75724). In a further charter from 1141 she confirmed a grant of lamds to this abbey (Add. Ch. 20420). Matilda was also a benefactor of Reading Abbey (Add. Ch. 19576, 19577, 19578 and 17579). Margery de Crek founded Flixton Priory in Suffolk in the years 1258-1259 (Stowe Ch. 291). Confirmations of her foundation followed quickly (Stowe Ch. 292, 293 and 294; LFC Ch. V 15) as did even a royal gift of land (Stowe Ch. 296), interestingly for having a warren, a terrain with rabbits. The more remarkable charter about Flixton Priory is the confirmation by a widow of receiving lands in 1263 for her dowry from the prioress of this institution (Stowe 305). Among the Stowe documents are eleven records with transactions concerning three monasteries in Brescia. Not as a founder, but as protector to a university acted queen Juana de Castile who put her seal to a charter establishing her in this role in 1510 for the university of Alcalà de Henares (Egerton Ch. 127).

Even when I will not unduly focus here on queens and countesses you can find glimpses from their surroundings as well. There is a successful petition by a nurse serving king Henry VI to double her yearly salary in 1424 from £ 20 to £ 40 (Stowe Ch. 643). A very different petition was sent to pope Calixtus III (1455-1458) by Vaggia, widow of Bernardo de Bardi from Florence, to gain permission for herself and her two daughters to have their confessor celebrate mass with a portable altar during an interdict and similar ecclesiastical measures (Add. Ch. 67089). By the way, the description in the overview of this document mentions pope Celestine III, but the description in the online catalogue notes the right pope. A third petition in 1455 comes from queen Margaret of Anjou to her husband, king Henry VI, about sums to be given to her through the Exchequer (Cotton Ch. XVI 72). Another document shows Margaret of Anjou in another role. She was taken prisoner in 1471 and delivered safely to king Louis XI of France in 1476 after he had paid a ransom of 50,000 crowns (Add, Ch. 13932). Margaret had been kept in custody by Alice Chaucer, duchess of Suffolk, formerly her lady-in-waiting. This is of course also an example of a woman figuring in both series of specially digitized documents.

One particular category of documents deserves here a bit more attention, even if it leads to inevitably arbitrary choices. I myself frowned when realizing the fifteen quitclaims contain renunciations of a right or rights. In what cases did women cede rights, and to whom did they renounce a particular right or some rights? The overview mentions almost always cases concerning rights to land ceded to either men or religious institutions. The term quitclaim is indeed reserved to cases concerning rights on lands or rents. One case involves a renunciation by Gonorra in the mid-thirteenth century of half a rent owned on lands given to a hospital in Southwark by her late husband William Bannastre (Add. Ch 23674). To this charter her seal is affixed, a reminder to look for seals of women and the way women are depicted on seals. Seven documents mention a rent or rents.

Let’s end an admittedly restricted choice of items in the second series with some documents which are in my view truly exceptional in the selection made by the British Library. Stowe Ch. XXXII 13 is a chirograph from 1355 with an arbitration by Thomas of Hampstead between Lady Katherine and her son John Latimer about her right to access the chapel at Braybrooke Castle. Another arbitration is found in Add. Ch. 28654. In 1352 an agreement was made about the access for the canons of Sankt Maria im Kapitol, Cologne, to the monastery led by abbess Elizabeth von Katzenellnbogen at this institution when they had to visit the chapter house. The arbiters confirmed in Latin an earlier verdict given in German included in this charter. Add. Ch. 27703 contains a covenant from 1380 between Joan, dowager of Wales, widow of Edward known as the Black Prince, and the community of Beverley in Yorkshire to pay to her an annual rent granted earlier to a kinswoman.

Finally it is sensible to note the only lawsuit among the newly digitized documents, a roll from the last decade of the fourteenth century with documents from of a case heard at Salisbury Cathedral between the abbess and convent of Canonsleigh Priory and parishioners of Morden, Dorset (Add. Ms. 52913). In 1392 the vicar-general of Salisbury judged in favor of the parishioners who had claimed the convent had failed to do an annual payment to the poor, forbidden them to cut woods in the cemetery, and the convent had diverted fruits from the parish church contrary to canon law to a layman.

Women in many roles

I did not write here about the four documents in the second series touching in some way on Flanders, and I have also skipped the manuscripts with rules and statutes. I did spot manuscripts from the Northern Netherlands, but these do not have a legal content. I could have delved into the many wills and grants, and looked in detail for the various motives formulated in these documents. I am afraid no one can present in a single blog post everything that makes this project so interesting! The British Library has made a fine selection of manuscripts and documents enriching our knowledge and helping us to ask questions about medieval women and their lives. Connecting some of the manuscripts with archival records and vice versa is just one of the possible routes to follow. Some archival records could equally be prized possessions of the National Archives, Kew or other record offices in the United Kingdom and even abroad.

It is only logical I could not open every window offered here, but I urge anyone to look at length and with lots of questions to the two overviews and the special web pages for some women to gain new insights into medieval lives and afterlife, not in the least to the legal sides of women’s lives to be found in these manuscripts and archival records. Any selection has its limits, but I think this project of the British Library is truly a gem.