This year I somehow evaded or skipped the remembrance activities and publications around the end of slavery in the former Dutch Suriname in 1863. Frankly, I even thought we had already had manifestations about the act of emancipation a few years ago, in 2013! To me it seemed not entirely just to neglect the continuation of slavery in other parts of the Dutch colonial empire after 1863. The death of Natalie Zemon Davis on October 21, 2023 helped me to remember she did research, too, on the history of colonization and slavery in Suriname. In this post I would like to bring some strands of thought together, both to make some amendments for my omission earlier this year and to salute the work of a historian who inspired fellow-historians worldwide.

Remembering Natalie Zemon Davis

French history was a key focus in the work of the late Natalie Zemon Davis (1928-2023). Much has been said the past weeks to honour her achievements, to remember with gladness her generosity and curiosity, and to put her scholarly work into various perspectives. She was a most inspiring example of a woman succeeding to enter into academia and reach the highest posts, thus opening doors for many other female historians. Social history gained its current position for Early Modern historians also to a substantial extent thanks to her pioneering research. I will not repeat here the fine tributes paid to her, such as those written by the faculty of history in Oxford, the Society of Renaissance Studies and the Central European University in Budapest. Some interviews with Natalie Zemon Davis remain very telling testimonies to her life, approaches and influence, for instance the one in Itinerario 39/1 (2015) 3-15, the 2008 interview for Medievalists, and for her connection to Suriname’s history the interview (in Dutch) originally published in the history journal Skript.

Three articles by Natalie Zemon Davis about Suriname attracted already years ago my attention at the blog Buku – Bibliotheca Surinamica of Carl Haarnack. He created digital versions – including PDF’s – of Davis’ articles on David Nassy (2010), colonial justice in Suriname (2011), and on Creole languages in Suriname (2009), originally published in Historical Research 82, issue 216 (2009) 268-284. Looking at the footnotes of these articles I smiled when read the old abbreviation A.R.A. for the Algemeen Rijksarchief in The Hague, now called the Nationaal Archief. Davis was about to finish a study on eighteenth-century Suriname, and hopefully this work can be published soon.

Approaching the history of Suriname

On several occasions I wrote here posts about Suriname’s history, for example ina post about slavery (2013), a post on archival resources for Suriname’s legal history (2017), the slave registers of Suriname (2018) and similar registers for the island Curaçao (2020), and last but not least a post concerning the city Middelburg in the province Zeeland and the role of its commercial company in the eighteenth-century Dutch slave trade (2021). These posts seem to me still interesting. The only snag with the oldest contributions are the changes in the way the Dutch national archives present their information online. The Nationaal Archief had good reasons to follow the example of the British National Archives to maintain two websites or at least separated subdomains for searching information about their holdings on one side, and on the other information about its organisation. Thus a number of links in my posts is now broken, because no action was taken to create redirects, in itself surely a major task, but not wholly strange to helping the general public, scholars and anyone interested and thus also providing stable services.

I had preferred not to add anything about the lack of true multilingual presentation and search interfaces on the current website of the Nationaal Archief. The current English version of the overview of indexes at the Nationaal Archief to many record series, including series on Aruba, Curaçao, Indonesia, Suriname and the two major trading companies for the Dutch East and West Indies, are shown with untranslated titles, referring you to the translation function of your browser which might not work as historically sound as proper translations would be. However, the new language button does now offer eight languages. Only for English a condensed standard version of the website exists. It is a pity you can navigate only in Dutch directly to the important zoekhulpen (research guides) on Suriname, Curaçao, Indonesia, colonial history and slavery. On the other hand, the website of the Nationaal Archief Suriname in Paramaribo seems to be entirely written in Dutch.

You might want me to end this lament and look at things differently! The really remarkable and even worrying thing to note is the lack of attention to the use and existence of exclusive language in finding aids and research guides, apart from notices in the guides for Suriname and Indonesia. The volume Staat & slavernij. Het Nederlandse koloniale slavernijverleden en zijn doorwerkingen [State and slavery. The Dutch colonial slavery past and its consequences], Rose Mary Allen et alii (eds.) (Amsterdam 2023), a major commemorative publication of historical essays accompanied by a website, pinpoints as one of the problematic things about doing research about the place of slavery in Dutch history the very use of language with its implications, explicit or hidden bias, political agendas or worse. The thirty authors in this volume wrote essays of generally ten pages, interspersed with short contributions on research methods and some sources, and some interviews. They cover subjects both about the past and the current Netherlands to highlight the fact vIews do not stem from a viewpoint above space and time. On purpose the articles on the oldest periods have been placed last, yet another way to break through commonly held assumptions, even if this reversal of chronological order and sequences has its setbacks, too. The great strength of this volume is the use of multiple perspectives and the wide coverage of themes and periods.

Finding digitized books on Suriname’s history

Reading Davis’ articles on the history of Suriname and visiting the Buku blog of Carl Haarnack rekindled my interest in finding online digitized materials for this subject. My own list of digital libraries concerning Suriname on my webpage for digital libraries was rather short, and thus I started to check the existing links and to search for other relevant collections.

Let’s start at Amsterdam. The old subdomain for digitized cultural heritage held by the Universiteit van Amsterdam responded with an error message. The combined special collections of the university library and museum Allard Pierson brings you quickly to its search portal with at the bottom of the landing page an overview of the main collections, including the Surinamica collection. The page for this collection does currently not point to the availability of digitized items. As in the old configuration books and prints have been digitized within the image database where an overview of digitized heritage collections is now very much absent. There is only a free text search, not an advanced search mode, but you can apply several filters for your search results. To the best of my knowledge it seems at first hardly any item has been newly digitized during the last five years or added to the hundred items. Even the major Suriname exhibition at Amsterdam’s Nieuwe Kerk in 2020 clearly did not work as a spur to digitize more items of this rich collection. However nice the new layout looks, navigating to the things you look for could considerably be enhanced. In my humble opinion a fresh look with a decolonizing view to the state of things at this website can help to make things truly accesible for anyone.

Leiden University Library manages also the collection of the KITLV, the Royal Dutch Institute for Caribbean history. Within the digital collections presented by the university library in Leiden there is no separate collection for Suriname. The number of results in a free search for Suriname is large, but a substantial number of items can only be viewed with restrictions. The catalogue of the exhibition Suriname in beweging (2015 is available online.

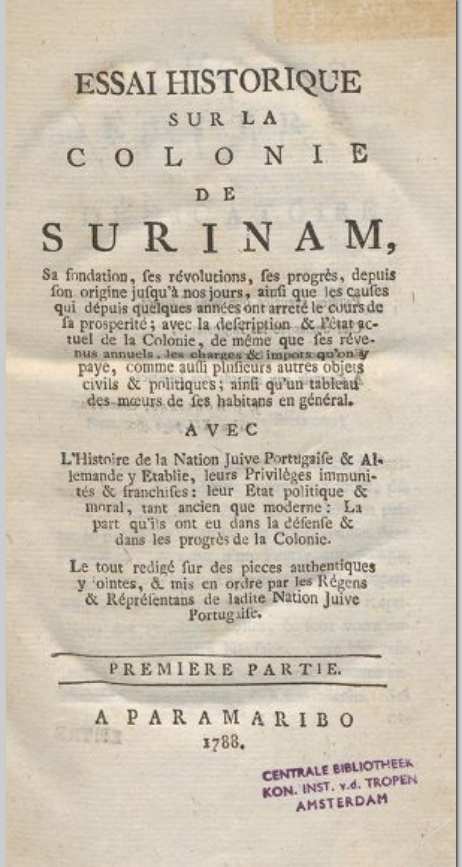

Natalie Zemon Davis was impressed by the Essai historique sur la colonie de Surinam (…) (Paramaribo 1788), written by a group of learned Jewish men with Portuguese ancestors. It was only natural for me to start searching for a digital version of this work, but it took a while to realize I searched for it with the name of just one author, David de Isaac Cohen Nassy, actually using only Nassy… In this book the names of the authors appear only in abbreviated forms. A number of libraries catalogued this work under the name of one of the other authors, Moses Pa. de Leon, the first name mentioned in the dedicatory letter. Several copies have been digitized by Google. At Leiden a copy of the KITLV has been digitized within the digital collections. The Hathi Trust Digital Library provides both the original edition and a digital version of a reprint (Amsterdam: S. Emmering, 1968).

At his blog Carl Haarnack pointed in 2013 at the Dutch version of this work, Geschiedenis der kolonie Suriname (…) (Amsterdam-Harlingen 1791). A copy of this work has been digitized for the Delpher platform. The Allard Pierson does itself no service by simply forgetting to mention at its website the earlier very substantial digital contributions to Delpher from 2013 onwards. Hiding an obvious and important thing is a neutral description of this situation. Luckily, the main library catalogue of the Universiteit van Amsterdam, CataloguePlus, does bring you safely and smoothly to items digitized at Delpher, even to its own digitized copy of the Essai historique. Delpher and other digital portals are mentioned on the help page for finding rare and old works. To be fair, it would be interesting to check the websites of other contributing institutions for any clear mentioning of their partnership with Delpher.

I would have dearly liked to sketch a more positive image of the current state of affairs concerning the digital presence of cultural heritage about and from Suriname at the two institutions presented here above, but it seemed helpful to give here more details and impressions about them. At my webpages on Old Dutch law and digital libraries in Europe you can find more Dutch digital libraries.

At Buku Carl Haarnack pointed in 2015 to the Suriname collection of the Herzog August Bibliothek (HAB) in Wolfenbüttel. He writes about a number of rare works touching Suriname. I checked for them in the general catalogue of the HAB. Soon I noticed not every work about Suriname has received this keyword as a major element in its catalogue record. You will notice with me the presence in this catalogue of digitized items held elsewhere. The webpage on the Digitale Bibliothek at Wolfenbüttel does offer much information, but it does not clearly state that the core digital collection of the Wolfenbütteler Digitale Bibliothek does bring you only to digitized manuscipts, worse from its main page you cannot even reach the search interface for its digitized manuscripts. Some stress on the fact digitized copies of Early Modern German printed works held at the HAB can be found quickly using the bibliographies VD16 and VD 17 would be useful, too. In my view here, too, the viewpoint from outside can help to fill such lacunae which hinder in particular new visitors. My deep admiration for the rich holdings at Wolfenbüttel and the fine fleet of digital initiatives of the HAB made me curious about this part of their collections, and I simply had not expected the present state of guidance.

The powers of history

Doing colonial history and invoking the help of digital libraries or archives is not yet as straightforward as you would like it to be. Historians past and present have to tackle hindrances and perhaps above all to recognize their own blind spots, the limits of their discipline and also the working of library catalogues, bibliographies and finding aids, be they in print or online. It can be fun to find out the tricks of the trade, but at the same time you realize how difficult it can be for outsiders to enter this world.

Natalie Zemon Davies shows for me her greatness again in tackling the difficulties of combining colonial and Jewish history with resources often but not only written in Dutch. It is now decades back I first read her books The return of Martin Guerre (Cambridge, MA-London, 1983) and Fiction in the archives. Pardon tales and their tellers in sixteenth-century France (Cambridge-Stanford, CA, 1987), publications I mentioned here in a post on the legal document genre of factums (2016). Natalie Zemon Davis loved telling stories which stand for much more than only their factual content. Fictionized tales and the very bias they show helped her to gain insights you might easily overlook. Her narrative approach was in a way also a quiet protest against too strong reliance on large datasets and statistical treatment of data. Musing about the impact of historians I was truly touched by the closing words of Natalie Zemon Davis’ contribution to the online series Why Become a Historian? of the American Historical Association. She expressed her enduring love for history, and wanted to see history as “a source of sober realism, but also a source of hope”.

A postscript

After correcting a number of typos, some of them rather silly, I realized something else, too, the omission of an important step by the Allard Pierson, the recent appointment of a staff member to investigate ways for decolonizing its heritage collections. Inadvertently I had also left a confusing sentence about its copy of the Essai historique sur la colonie de Surinam. The Allard Pierson’s copy has been digitized and is available at Delpher.