In December 2022 I first spotted SION-Digit, a research project aiming at using notarial acts from Venice, Bordeaux and Amsterdam to gain new insights into Early Modern Jewish history. Project leader Evelien Chayes received in 2022 media attention for her discovery during this project of a rare letter by Michel de Montaigne amidst records from a notary’s archive held at Bordeaux. Even with only a project blog I think SION-Digit deserves attention here for its goal of using legal records as a historical source showing much hidden things about the history of Jews in Early Modern Europe. One of the things to investigate is the role of digitized records for this project.

Notarial records, a rich resource

Three archival institutions have a pivotal role for the SION-Digit project, the Archivio di Stato di Venezia, the Archives départementales de la Gironde in Bordeaux and the Stadsarchief Amsterdam. The first section of this post will help to come quickly closer to some of the advantages or hindrances to study notarial acts at the three institutions.

The Archivio di Stato di Venezia (ASV) recently launched a nicely designed search engine, moreveneto for searching the many fondi. At first I was slightly disoriented, seeing on one side two collections for notai but also more than 1400 other collections. Using the term notarili brought me to twelve fondi in the 3500 Notarile record group. Fondo 3520 contains indici per parti contraenti per notai, without an indication about the period and only a general statement these indices being incomplete, and fondo 3550 with general chronological indices, however, only for the period 1801-1829. Another attempt at using the general search interface led me to fondo 003, Notarile. Testamenti. Indici with indices for wills from the period 1300-1802, with four subseries. Of course it will take you some time and effort to get used to any guide. Apart from the concise guidance in the section Patrimonio of moreveneto you can used the section Galleria, where I got 13 results for notarile and 8 results for notai, bringing you mostly digitized repertories, but also some notarial records.

At the website of the state archive in Venice you will note with me at Risorse in rete that two earlier online resources, including the digitization platform Progetto Divenire and an earlier online guide, are now part of moreveneto. However, it is not mentioned the ASV contributed also digitized materials to the platform Judaica Europeana, now maintained by the Jewish Heritage Network. The Brandeis University helped creating digital access to eighteenth-century pinkasim, community ledgers held at the ASV.

The website of the departmental archives for the Gironde region in Bordeaux brings you quickly – starting with Recherche and choosing Thèmes – to information about notarial records in their holdings. There is an online search form for the minutier des notaires, where you can search for names, places, and periods, and filter for some specific document genres or limit your search to either minutes or repertories. The AD Gironde holds now some 7 kilometer of notarial records. You will find also a digitized biographical register of notaries created by a group of volunteers between 1987 and 1998. The État général des fonds, too, leads you to this repertory for notaries.

Notarial acts from the Stadsarchief Amsterdam have been presented here already in a number of posts, for example in a post about Rembrandt’s life. In fact this resource genre received much attention from this institution recently. This has resulted in the creation of indices for a great number of acts, now integrated into the general search platform. You can limit your search to particular document genres. At the transcription platform Vele Handen [Many hands] two projects deal with notarial records from Amsterdam, Alle Amsterdamse Akten for creating indices, and Crowd leert computer lezen [Crowd helps computer learning to read] for creating a Transkribus base ground which led to two online public models for computerized transcription, the first for seventeenth-century notarial acts and the second one for the eighteenth century.

In a third project at Vele Handen together with other institutions the Stadsarchief Amsterdam let volunteers add tags to a number of transcribed notarial acts. The results can be found at the Transkribus subdomain Amsterdam City Archives. Interestingly, you can adjust the search mode for fuzzy results. By the way, at the portal Zoek in transcripties [Search in transcriptions] with the other tagged acts from the third project at Vele Handen you will find apart form VOC records as its core a nice selection of notarial records from Dutch provincial and regional archives.

The city archives of Amsterdam offer a concise online introduction to the indices for notarial records, and you can download the repertory of Early Modern notaries created by A.I. Bosma, Repertorium van notarissen residerende in Amsterdam Amstelland, ambachtsheerlijkheden en geannexeerde gemeenten 1524 – 1810 (1998) as a PDF.

Objects, texts and networks

The SION-Digit project has objects, texts and networks as its main focuses. By choosing three towns with a busy harbour the network side of things has surely a good foundation. The transport of people, objects, letters and ideas was very much helped from these towns. A principal aim of this project is to use the wealth of information in notarial acts for delving deeper into Early Modern Jewish history. The core of the project is using and creating digitized access to notarial deeds. At the project blog it is asserted until now state and town archives have not been used as much as the records held at specialised institutions for Jewish history.

The flat statement on the SION-Digit blog notarial acts in these three towns are hard to find or difficult to access is in dire need of some qualification. Luckily the French version of the project aims does not contain this lapidary statement. In view of the repertories for notarial registers at all three archives discussed here above it is simply not true one cannot find these registers or that there are severe blockades for finding them. At Venice there are indices for acts contained in notarial registers. In Bordeaux you can use the online search for the minutier and even find biographical information about individual notaries. The city archives of Amsterdam offer an online repertory of notaries, you can search directly for notarial registers in finding aid 5075, and there are online indices and digitized registers. For a fair number of registers you can even benefit from computerized transcriptions.

The problem for researching these Early Modern notarial acts is the degree of accessibility of individual acts. I guess the project description at the SION-Digit blog stems probably directly from a project proposal for funding, with alas a not uncommon exaggerated picture of gaps to be filled, hidden materials and great vistas awaiting at the completion. More to the point is the wish to combine materials from notarial records with existing projects for pinkasim, Early Modern Jewish community registers. In particular the Pinkasim project of the National Library of Israel is important in this respect. It offers an online repertory of this document genre and digitization of a number of registers stemming from several European Jewish communities. There is also a very extensive bibliography.

Instead of looking here somewhat closer at pinkasim I thought it would be more useful to look at notarial records about Jewish communities in Early Modern Europe. Gaining an overview of such records is helped by the existence of the European Jewish Archives Portal, created by the Yerusha network and the Rothschild Foundation Hanadiv Europe. The portal does list archival collections held at European archives, libraries, museums and documentation centers. There is both a simple search and an advanced search mode, and also an interactive map for finding locations. Very useful are the possibilities to use other spellings, translations and transliterationd of names and locations.

As with all portals and search machines aiming to give complete coverage of any particular subject the search results at Yerusha are subject to the primordial factor of relevant data being available and entered into them. A quick simple search at Yerusha for notaries and notarial records does bring you to descriptions at collection level of archival collections in many European countries, but currently not from France and the Netherlands. For Italy only notarial records at Mantua and Milan are presented. It will do no harm to note the current absence in the Yerusha portal of any information from French and Dutch institutions. The interactive map for holding institutions helps you to detect such gaps.

I will not try to fill in this post all such real or supposed gaps. Within the Italia Judaica portal of the Goldstein-Goren Diaspore Research Center, Tel Aviv University, there is a fine introduction for Venice (in Italian) with a bibliography and footnotes, but alas without any direct reference to notarial records. By the way, the city Venice offers a concise guide to comunal and other archives in Venice. The SIAR is a portal to archives in Venice and the Veneto region. I looked briefly at the website of the Commision Française des Archives Juives (CFAJ). Among the links the CFAJ mentions are the city archives of Bordeaux, and I might as well put here the current link to the Archives Bordeaux Métropole.

Any temptation to go further here with listing my own selection of either randomly or specifically found resources was checked to some extent by visiting the portal site Jewish Heritage Network, another initiative of the Rothschild Foundation Hanadiv Europe, with due attention to archival collections held by institutions for Jewish cultural heritage in Europe. However, it seems not amiss to start looking for notarial records at another central point, the Archives Portal Europe, and to benefit from the search facilities for Dutch notarial acts at the Archieven portal, because many Dutch archives have created indexes for this document genre. If you want to look further for Jewish archival collections, some of them even digitized, I can refer you to my own web page for digital archives with relevant links for a number of countries and periods.

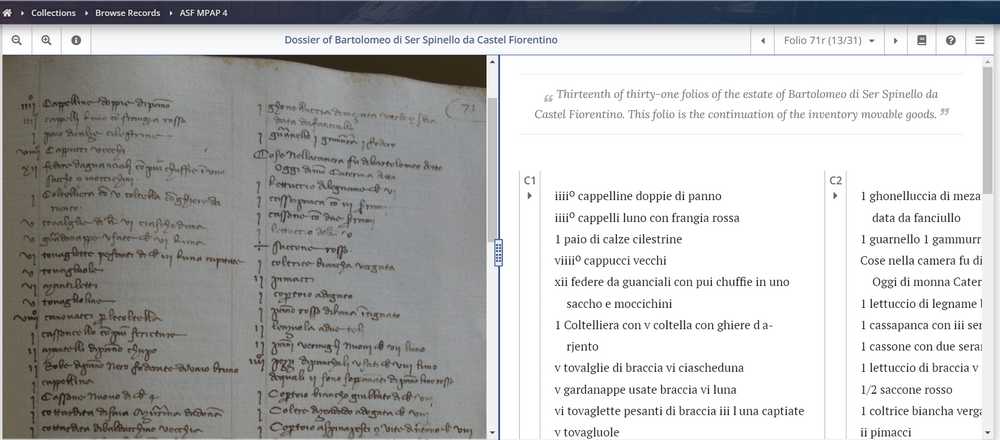

As for notarial records in France it is good to note here the Minutier central des notaires de Paris. The Université de Tours has created the platform Renumar for searching late medieval and sixteenth-century notarial acts from Tours, Amboise, Bourges, Chartres and Chinon. With this project associated is LECTAUREP, an initiative for computerized use of notarial records. In Italy and Spain are several projects which focus on medieval notaries. You can quickly perform yourself a search for minutes notariales and related resources at the French portal FranceArchives to check where you can find them and to see where such records have been digitized.

SION-Digit in action

On October 25, 2023 SION-Digit organizes a symposium ‘Au-delà de l’assignation géographique: Portraits des juifs dans l’Europe prérevolutionnaire’, to be held at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme in Paris. Earlier on, in September 2022, the project team organized in Bordeaux a round table on Jewish testimonies in Early Modern France. This year SION-Digit received support from the Biblissima platform. On the central website of the Institut de Recherche d’Histoire des Textes (IRHT) there is no additional information about the contents of SION-Digit, sometimes also referred to as SION-Digit Sfarim.

The project blog brings you to more information about the newly found letter by Montaigne, for example an article in Dutch from the newspaper NRC Handelsblad on August 10, 2023 (PDF). Chayes wrote with Alain Legros, ‘Un brouillon inédit de Montaigne parmi des actes notariés’, Bibliothèque d’Humanisme et Renaissance 85/1 (2023) pp. 87-95. At the 2022 meeting of the Renaissance Society of America Evelien Chayes spoke about Letizia Nahmias, a remarkable woman in the seventeenth-century Venetian ghetto. It led to an interview by Esther Voet for the Nieuw Israëlitisch Weekblad 39 (July 8, 2022) pp. 24-25, ‘Een onafhankelijke vrouw in het ghetto’. Finding Letizia’s will was a key moment in understanding her life and actions which were for a long time overshadowed by her husband -also her nephew – who converted to Catholicism.

With SION-Digit we meet an international project on a vast scale developed and for some part to be executed single-handed by a scholar who is at home in the study of Early Modern literature, book history and library history. Her goal of bringing scarcely known aspects of Jewish lives and history into the limelight by using notarial acts should command respect. SION-Digit should invite and deserves support from those scholars better acquainted with notarial records in Italy, France and the Netherlands. The fact Evelien Chayes pinpoints women’s history as a key to detect networks is another stimulating aspect of this project. I wrote here at some length about SION-Digiti Sfarim exactly because Chayes wants to use sources too easily labelled as a territory of legal historians, local historians and genealogists. It is to the benefit of anyone who becomes fascinated by a particular source genre to meet others with their questions, approaches and tools, and to receive mutual support. Connecting scholarly research in various disciplines to gain insight into peoples and networks that tend to be overlooked is in my view a most valuable effort. Mazzeltov, good luck!

A postcript

For finding digital projects concerning Jewish history you can benefit from another international portal, #DHJewish: Jewish History and Digital Humanities, supported again by the Rothschild Foundation and maintained by the Luxembourg Centre for Contemporary and Digital History (“C²DH”). #DHJewish offers also an online bibliography at Zotero.