In 2022 a celebration around the Bibliotheca Thysiana in Leiden could not take place as scheduled. Only now a volume of essays appeared celebrating the rich diversity of the collections in this remarkable public library from the seventeenth century, Tot publijcque dienst der studie. Boeken uit de Bibliotheca Thysiana, edited by Wim van Anrooij en Paul Hoftijzer (Hilversum 2022). Johannes Thysius (1622-1653), a young Dutch lawyer from a rich Flemish family, succeeded in buying during his short life a remarkable collection of books and pamphlets. Luckily his last will contained provisions to maintain this collection together in a library building he never saw himself, now still gracing the Rapenburg canal in Leiden. In this contribution I want to look at three recent publications about Thysius ands his library, I will also provide a concise guide to the contents of the printed collections pointing you to online resources, and to the archival collection, too.

Providing books to the public

Founding public libraries was still a novelty in the first half of the seventeenth century. Thysius had visited the Bodleian Library in Oxford and the Bibliothèque Mazarine in Paris. With its numerous auctions of private collections the book market in the Dutch Republic was long unique in Europe, a matter noted here in my review of the study of the Dutch book trade and production of printed works by Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen. In a more recent study, The library. A fragile history (London 2021) both authors look at the problems faced by book collectors and libraries throught the ages to create and maintain collections. Thysius definitely took some very wise decisions following the most sensible advice of his time, by providing in his last will a number of conditions to give his library a sure foundation. His immense wealth was a prime factor for the successfull execution of his plans, and the fact he was unmarried, mentioned specifically by Pettegree and Der Weduwen (The Library. A fragile history, p. 191). Putting his collection in a purposedly-made building was one of the favorable conditions, as was providing funds for new acquisitions and curating the collection. It must be said that the care for the books did not always reach the level Thysius had wanted. At least one curator proved almost disastrously incapable, and contrary to appearances the collections now housed in the building on the corner of the Rapenburg and the Groenhazengracht are not without their losses. A number of books has simply been sold. Leiden University now curates the Bibliotheca Thysiana aided by a foundation with Van Anrooij and Hoftijzer among its directors working together with the Leids Universiteitsfonds.

The number of legal books bought by Thysius is unexpectedly relatively low compared to other book genres. The new volume with ninety rather concise essays aims at showing the diversity of works present in the holdings of the Thysiana. The essays, mostly written by scholars with clear connections to Leiden University, each cover just two pages, one of them a full-page illustration, often the title page or an illustration. References to scholarly literature have been placed in an appendix. The book contains an index with brief notices on the contributing authors, and indices for locations and persons mentioned in the essays. I cannot help seeing a clear paradox between the wish to present this wonderful diversity of subjects and the demand for utter conciseness about each book. Visitors at the Thysiana complained often about the restricted number of works shown to them. Even (abbreviated) references to standard bibliographies for incunabula and Early Modern books are absent, probably a first for Paul Hoftijzer in his rich scholarly output on Dutch book history. I will deal with (online) resources for finding books and pamphlets at the Thysiana in the next section.

Four authors received an invitation to deal with subjects touching legal history. Let’s look at them here somewhat longer. Martine van Ittersum, ‘Een roofdruk in de Bibliotheca Thysiana’ (pp. 38-39). deals with a pirated early edition of John Selden’s Mare clausum published in Amsterdam in 1636 [THYSIA 92). An English ban on this edition luckily did not prevent the survival of a number of copies. C.H. van Rhee, ‘De rechter en zijn vonnis’ (pp. 62-63), presents the Lyon 1606 edition of a work by Jacobus Menochius, De arbitrariis iudicum quaestionibus et causis, a monograph on the discretionary power of judges (THYSIA 352). Menochius probably wrote this work in order to become a judge. In 1592 he became a councillor on the senate of Milan. Hans Trapman, ‘Kettervervolgingen in de Nederlanden en Spanje’ (pp. 152-153), discusses a treatise by François du Cheyne (Francisco de Enzinas), Histoire de l’estat du Pais Bas, et de la religion d’Espagne (1558; THYSIA 1717) on the persecution of heretics in the Low Countries and Spain. Enzinas himself was arrested in Brussels as an heretic in 1543, but he could escape from prison in 1545. Finally, Arthur der Weduwen contributed ‘Rechtsnoer des rechts, breidel des onrechts’ (pp. 162-163), an essay on the first printed collection of ordinances issued by the States of Holland, the Hollandts placcaet-boeck (Amsterdam, 1645; THYSIA 2041). This volume was edited by Beuckel van Santen, a former bailiff of Blois. The title of this essay is a quote from his introduction, where he states the prosperity of Holland is due to the laws created by the States of Holland, “a guideline to justice and a scourge of injustice”. For all their brevity these essays are certainly worth reading, and this volume shows indeed the diversity of the Thysiana’s holdings in many aspects. I really cannot make a choice to write here about essays on other books, be they a manuscript with music for lute, a copy of the famous Manutius edition of the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a treatise on optics, an attempt at deciphering hieroglyphs or books dealing with Persia, China and japan.

A configuration of publications and resources

The volume by Van Anrooij and Hoftijzer is in some way a logical sequel to two other recent books. The same authors published Vijftien strekkende meter. Nieuw onderzoeksmogelijkheden in het archief van de Bibliotheca Thysiana (Hilversum 2017), a volume with articles showing the possible use for research of the recently published inventory by Arend Pietersma and others for the archival collection of the Thysiana and the Thijs family held at Leiden University Library, Inventaris van de archieven van de Bibliotheca Thysiana en van leden van de familie Thys en aanverwante families, 18e-20e eeuw (Leiden, 2013; collection no. ubl207; online, PDF). This inventory replaced the incomplete finding aid created by B. van Roijen in 1941. At pp. 11-14 you will find the text of Johannes Thysius’ last will and codicil (ATH, inv.no. 10).

In the 2017 volume Arend Pietersma highlights the core themes of this ensemble of archival collections: family, trade and science. He mentions the two facts best showing the wealth of the Thijs family: Hans Thijs sold in 1611 the home of his parents, De Wapper in Antwerp, to the painter Peter Paul Rubens, now known as the Rubenshuis, and Christoffel Thijs sold in 1639 his house in the Jodenbreestraat to Rembrandt van Rijn, now called the Rembrandthuis in Amsterdam (pp. 18-20). Johannes Muller looks at the Thijs family as a merchants’ family with a large European commercial network with many Flemish migrants. The Thijs merchants traded in particular jewellery and furs. In his contribution Lodewijk Petram underlines the importance of the correspondance, registers and the contracts of members of both the Thijs and L’Empereur familes, rare survivals, as is Thysius’ own meticulously kept register of incomes and expenses including sums spent on books (ATH 434), a true window on trade in the booming Dutch Republic. There is a manuscript with a draft book catalogue (ATH 430), and even receipts of book purchases. Other articles in this well-illustrated volume – including images of archival records – deal for example with the manuscript containing lute music (THYSIA 1666), and the role of music for Johannes Thysius (Jan Burgers). Martijn Storms analyses a map showing the landed property in Voorschoten which formed the financial basis for the maintenance of the Thysiana. Esther Mourits looks at documents with information about the private life of Johannes Thysius. His mother, Elisabeth Hedwich de Baccher, died at his birth in 1622, and when he was ten years his father Anthoni Thijs died. He moved from Amsterdam to live with his guardian Constantijn L’Empereur, a Leiden professor of Oriental languages, who had married in 1628 Catharina Thijs, an aunt of Johannes.

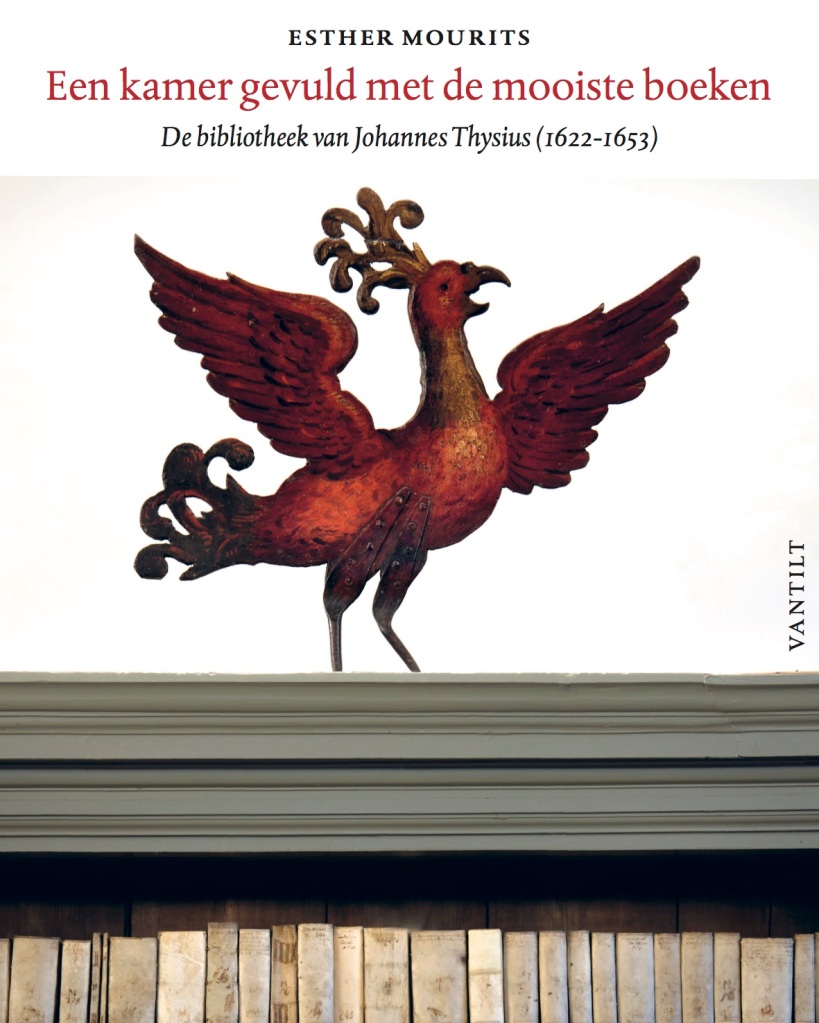

The other recent book Van Anrooij and Hoftijzer refer to is the major study by Esther Mourits, Een kamer gevuld met de mooiste boeken. De bibliotheek van Johannes Thysius (1622-1653) (Nijmegen, 2016). You can download the identical version of her work, defended as a PhD thesis in 2016 at Leiden (PDF, 266 MB). Mourits’ study deals both with the Thysiana and with Johannes Thysius. She concludes he was more a wealthy and avid book collector than a scholar. Een kamer contains a long chapter on the holdings of the library (pp. 147-245), with a discussion of the juridical works, too, including a comparison with other private collections of legal books in Leiden (pp. 162-182). She deals briefly with the pamphlets (pp. 157-159 and 244-245), because this genre deserves in her opinion a separate study. In Tot publijcque dienste der studie the editors give a splendidly illustrated sketch of the history of the Thysiana (pp. 18-32). They show for example the special cupboard for Blaeu’s Atlas Major and the famous wooden book mill from 1648.

The position of pamphlets within the Thysiana

Van Anrooij and Hoftijzer do not mention all catalogues and online resources for the books and in particular for the pamphlets of the Thysiana. All works can be found in the online catalogue of Leiden University Library. The editors rightly mention the catalogue by P.A. Tiele, Catalogus der bibliotheek van Joannes Thysius (Leiden 1879; online, Internet Archive). Incidentally the digitized copy DOUSA XXXX contains additions and pencilled shelfmarks, and a note from 1921 by historian P.J. Blok about the archive. The editors refrain from indicating the existence of the four-volume catalogue for the rich holdings in Dutch pamphlets, although there was enough space to mention it. The existence of ths catalogue conflicts with the assertion by the editors Tiele’s catalogue is the most complete catalogue for the Thysiana (p. 17).

Tiele mentioned in the foreword to his catalogue (p. IV) as the first catalogue of the Thysiana an undated printed catalogue without a title page, but starting with the word “Catalogus bibliothecae Joan. Thysii”, dated in the online catalogue around 1650 (Leiden University Library, THYSIA 258; online), followed by catalogues published in 1677, 1739 and 1852. On the same page Tiele asserts without further ado that the Thysiana is most known for its collection of pamphlets. Van Anrooij and Hoftijzer ascertain as date of creation for the first catalogue in or around 1668 (Tot publijcque dienst der studie, p. 22).

The learned editors had a year to reflect on their own joint introduction for which they provided footnotes. It will do no harm to inform you here about access to the pamphlets at the Thysiana. Among catalogues of Dutch pamphlet collections the Bibliotheek van Nederlandsche pamfletten, Verzamelingen van de bibliotheek van Joannes Thysius en de bibliotheek der Rijks-Universiteit te Leiden, L.D. Petit and H.J.A. Ruys (eds.) (4 vol., The Hague-Leiden 1882-1934; online, Hathi Trust Digital Library) stands out for its sheer volume. Only the Knuttel catalogue for the Dutch Royal Library is more voluminous. The first volume deals with pamphlets published between 1500 and 1648, the second volume covers the years 1649 to 1702, the third 1703 to 1800, and the last volume is a supplement with concordances to other Dutch pamphlet catalogues acting as a complete catalogue of the Thysiana’s holdings in pamphlets; the number for the Thysiana refer to their place in the old portfolio’s. Petit had decided at first not to mention the works already described by Tiele in the pamphlet catalogue for Frederik Muller and by Van der Wulp for the collections of Isaac Meulman, and thus he could restrict himself to some 4,700 of the 12,500 pamphlets printed upto 1702. Luckily Tiele had prepared descriptions for the works published until 1659. The fact Petit could mention a total at all shows he relied indeed on Tiele’s work. By the way, the descriptions of works in these nineteenth-century catalogues are very concise.

The Petit catalogue deals only with works in Dutch. The 1934 supplement by H.J.A Ruys redeemed this omission. Thus it became visible you can find at the Thysiana for example also numerous mazarinades, seventeenth-century pamphlets against cardinal Mazarin. Both Petit and Ruys do not give shelfmarks for the works they described. It is not sensible to hide the state of affairs around these pamphlets. Some sentences at p. 17 of the essay volume pointing to the core facts about the pamphlets, and sending you to the website of Leiden University Library would have been very helpful, for example to the online guide for the pamphlets (collection ubl170). The efforts of librarians and other scholars creating retrospective bibliographies with the word catalogue in the titles of their work can still confuse modern users, and vice versa a finding list of rare printed works with the title word bibliography can make a deceptive impression.

Leiden University Library has only a very concise web page about the Thysiana. However, the departmemt for Special Collections has created a selection of some 880 pamphlets within the Digital Collections of Leiden University Library, with on the start page the very motto “For the public benefit of study”. This web page offers you four (!) guides to the collections of the Bibliotheca Thysiana and also the finding aid for the archival collection of this library and the Thijs family. Earlier on the digital selection contained some 240 pamphlets, all with shelfmarks THYSPF. You will need both the Petit-Ruys catalogue and the online catalogue of Leiden University Library. I found in the online catalogue nearly 18,300 works with the shelfmark THYSPF, and 5,250 works with the shelfmark THYSIA. I agree with the online guide to the Thysiana pamphlets the online catalogue is essential for actually tracing a pamphlet held at the Thysiana. It is a bit confusing to read in the guide the Dutch pamphlets received their shelfmarks using a catalogue by Tiele written in 1858 (i.e. 1868, OV), as are the totals of 16,279 Dutch pamphlets and 582 items in other languages. The totals are indeed higher according to a two-volume index to the pamphlet catalogue held in the Thysiana archive (ATH, inv.nos 260-261) which counts 18,938 items. Both the archive and the pamphlets are now housed at Leiden University Library.

A time capsule or a phoenix?

For me the Bibliotheca Thysiana has to some extent the character of a time capsule. Its architecture and the location with large windows to the north on the long side are remarkable. The cool light within the library room is difficult to capture in photographs. When you climb the stairs to the first floor and look around, you truly can imagine stepping back into the seventeenth century in a place where time comes to a halt. Nevertheless the history of this library shows definitely how changes did affect the building, the books and their use. Between 1997 and 2001 the building at the Rapenburg has been restored. The stair was made after drawings, because the original stair had been replaced in the nineteenth century. The pamphlets were taken out of their bindings, making it very difficult to establish the exact time of acquisition. A phoenix just happens to be a symbol in this library, both on top of the shelves and as a stamp in almost every book. Renewal under the surface of a seemingly unchanging configuration is closer to the mark as a decisive element in the history of the Thysiana.

The inventory and three books presented in this post help a lot together to get closer to the story of a seventeenth-century book collector, his life and passions, and above all his legacy of a library in a monumental building at Leiden’s beautiful Rapenburg canal close to the university. The books and other printed works also made clear that only patient research and reflection in the available sources can bring you reliable knowledge about Thysius, his library and family. The chance to study a library with substantial original holdings and the archival collections connected with it is rare and can yield rich fruits.

When dealing with pamphlets, and in particular with such a large collection as here, one has simply to accept the challenges to study them in any depth by mastering and marshalling all possible resources. I had expected Paul Hoftijzer to point at least at some of the resources and difficulties, and to share more of his experience in researching the Dutch book world in the Early Modern period. Earlier on Paul Hoftijzer and Otto Lankhorst excluded after careful deliberation virtual resources from their fine manual for Dutch book history Drukkers, boekverkopers en lezers tijdens de Republiek (2nd ed., The Hague 2000). Some caution was needed twenty years ago, but now even printed bibliographies have been turned into online resources. In my view the crucial point remains posing the right questions, finding a way to answers with reliable resources, and checking the facts. In my view the subject of Thysius and the Thysiana is still not exhausted. Pamphlets, ordinances and other ephemeral printed works made up the majority of the print production in the Dutch Republic. Johannes Thysius and his library are privileged witnesses to this situation. Studying this subject will certainly bring benefits to the study of book history and legal history, too.