Several scholarly projects have created online access, in repertories or digital versions, to Early Modern letters, in particular for a number of famous writers and scholars. Less attention seems to go to mail delivery in Early Modern Europe. Lately I encountered the research blog of Eric Vanzieleghem (Brussels) who charts French legislation on postal services from the fourteenth century onwards, focusing in particular on postal services during the Enlightenment. By chance I also spotted the website of a research project about Early Modern itineraries and travel guide books aiming at gaining more insight into networks connecting European towns and people. In my view it is fruitful to look at both projects together in a single contribution. A book with images and transcriptions of Dutch letters from many centuries gave me the final push to start this post.

You’ve got mail

Choosing correspondences as a subject goes clearly against the trend of the hyperquick social media and the continuous instant arrival of bits of information at our computers and mobile phones. Letters with their sheer length, the impatience of waiting for the postman to arrive, and the sense of expectation when opening a closed envelope have become rare. To be honest, I like to delve into Early Modern letters, but as a legal historian I hesitated to express this interest! Physical post might be less important now, but we all want to be kept posted on developments, and bloggers keep posting their contributions.

A look at the blog directory of the Hypotheses blog network earlier this year brought me to the blog Histoire du courrier dans l’Europe des Lumières created by Eric Vanzieleghem. Research concerning the letters of Condorcet led him in 2022 to start investigating legislation about postal services in Early Modern France. Vanzieleghem rightly started with defining the main concepts concerning post and postal services, and before I knew it he had me hooked in. The French word courrier was first used to refer to the actual carrier of letters, while nowadays it means the entirety of packages, written and printed matters send by post. The word poste literally stems from the stations where one could change horses. It referred to the distance between them and the network of these posts. Only since the nineteenth century its meaning changed into the desigination of state or private postal services. Vanzieleghem promises us an arricle about the eighteenth-century ferme générale des postes, and this office brings us close to the French government and administration during the Ancien Régime.

Until now Eric Vanzieleghem has published only six posts. One of them gives you the text of a royal ordinance from 1673 which adjusted postal regulations after the Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle (1668) and the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1673). I found in particular the tariff for postal service in force between 1703 and 1759 very interesting. It deals both with French regions and with a number of European postal routes. The payments due for a trajectory changed markedly when passing through particular towns. Part of the reasons behind these differences stem clearly form the very itinerary you letter had to go. In the second section of this post itineraries and travel guides will come into view.

Vanzieleghem gives us a list of the eighteenth-century correspondences used for his research. Both online versions of well-known corresponces fiugure here, buyt alo some very recently edited letters of more unfamiliar persons. He alerts to the recent discovery at the National Archives, Kew, of 75 letters written in 1757 and 1758 captured from the French navy.

His page on legislation is of course a key element for my posts. Van Zieleghem righly looks far and wide to find royal ordinances from 1315 onwards and revolutionary legislation upto 1801. The famous Receuil général des anciennes lois françaises (…) edited by François-André Isambert and others (29 vol., Paris, 1821-1833) does not contain every relevant ordinance until 1789. The Receuil d’Isambert is available online among the digitized legislative resources in the section Essentiels du droit of Gallica. The chronological list does not (yet) contain references for every ordinance in it, let alone links to digitized editions, but there is a brief overview of the main resources used sofar. It seems Vanzieleghem has found a lot of revolutionary decrees and laws, but he does not refer to the online Décrets et Lois 1789-1795: Collection Baudouin and La loi de la Révolution Française 1789-1799 on which you find information here in a post I wrote in 2022.

At the page Références of his blog Vanzieleghem offers a bibliography with several sections. Apart from scholarly literature for France he mentions a few titles for Italy and Switzerland. He also includes a list with a number of Early Modern books about letters and postal services, some of them with links to digitized versions. Vanzieleghem has either made a very strict selection of works or he has not (yet) used the online Bibliographie d’histoire du droit en langue française (Université de Lorraine, Nacy-Metz), searchable in French and English. For the maritime postal services he has found more titles than currently present in this online bibliography.

Early Modern itineraries and digital humanities

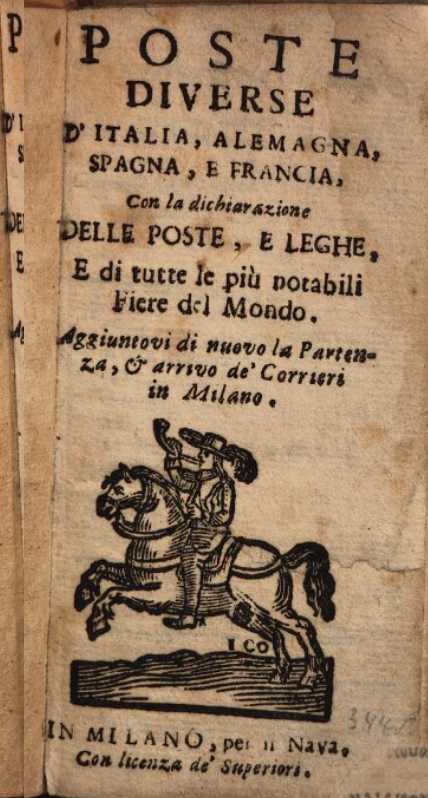

The research project Early Modern Digital Itineraries (EmDigit) is led by Rachel Midura (Virginia Tech). Her project team aims at mapping itineraries in Early Modern travel guide books on maps, using these data to build a project in the field of spatial history. Midura explains the aim of EmDigit using as an example a rare early Italian edition, Poste diverse d’Italia, Alemagna, Spagna, e Francia (Milan, [1550]). This edition is not recorded in EDIT16 and the Universal Short Title Catalogue; the union catalogue of the Servizio Bibliotecario Nazionale does not mention any copy of it in Italy. The only known copy has been digitized in full color by the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich, however, with currently as inferred date of publication around 1620. This change of seventy years came possibly after comparison with a copy of the edition Milan 1647 held at the library of Munich University, but more probably in view of the activity in and around 1622 of the Milanese printer Nava as shown in the Heritage of the Printed Book Database. The HPB database currently repeats the date around 1550 for the book Midura presents at EmDigit. I will look here at other elements and arguments for datation of this rare book.

The book gives the distances between cities, adverts you about the differences in length of the mile in countries, and contains detailed information about the dates of European year markets, a concise pilgrim’s guide for the Holy Land, and the dates of the weekly departure and delivery of mail for particular itineraries. Midura plotted the resulting data on a map of Europe. As for internal evidence for the date of production of this work, on pages 15 and 26 it is stated Vienna is the current residence of the imperial court, which suggests 1529 as a terminus post quem or the period after 1620. Maybe Midura has been misled by the black-and-white version available online in Google Books with the old datation 1550 given in 2014. It seems she simply did not check the bibliographical information at its ultimate source. Luckily Midura provides at GitHub a PDF with a very substantial list of printed itinerary books between 1545 and 1747. This list provides you with a basis to add further works, for example more translations of some of the works mentioned. Midura points to two editions of a Dutch translation of Georg Kranitz’ Delitiae Italiae. Works in Dutch can be traced using the Short-Title Catalogue Netherlands (STCN), now online at the CERL platform.

Midura noted on January 1, 2024 in the ReadMe document and the GitHub startpage of EmDigit the problem with the datation of the Poste diverse edition; she opts for a datation around 1700. She does not mention the new date around 1620 proposed by the librarians in Munich, and she points to just a single other digitized itinerary held at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. An online search in the Karlsruher Virtueller Katalog – with a search interface in German and English – will quickly bring you to more relevant digitized works held at this library and elsewhere.

The bibliography by Madura shows very clearly some titles took over advertising claims from other books, and perhaps even more for their contents. The GitHub page of Midura for EmDigit gives you access to the various digital components of the map with the postal routes. The spatial dimensions of the post routes in Early Modern Europe are certainly clear, but their presence in any particular short period needs further elaboration and some basic work, starting with using more printed itineraries and widening also the list of secondary scholarly literature. Midura tells you more about her project in the article ‘Itinerating Europe: Early Modern Spatial Networks in Printed Itineraries, 1545–1700’, Journal of Social History 54/4 (2021) 1023–1063. Midura was also involved in developing a transcribing model for Transkribus, Italian administrative hands 1550-1770. In a period of 150 years Europe changed drastically, if only becaure of long wars, and thus it is vital to locate information both in space and time. Midura uses some eighty itineraries for her project.

The EmDigit team organizes in 2024 several workshops. Midura announces on X (Twitter) she is going to publish her study The Tassis Family and Communications Revolution in Early Modern Europe in open access. I was particular happy to see her announcement, because it can form a bridge to the third and last section of this post around a book on letters from the Netherlands.

Post Scriptum

Letter writing comes in various forms and genres. Recently I was delighted to pick up a copy of a book by Jet Steinz, P.S. Van liefdespost tot hatemail. De 150 opmerkelijkste Nederlandse brieven [P.S. From love letters to hate mail. The 150 most remarkable Dutch letters] (Amsterdam 2019). Steinz found a great way to organize her book and to give it more impact. She organized the letters by genre in chronological order, and she presents each letter with images of the original in full color and a transcription. For older letters she sometimes rephrased the wording for smooth reading in modern Dutch. Letters in foreign languages have been translated. Only the relatively small format (18 by 23 cm) prevents it from truly becoming a kind of palaeographical atlas for late medieval to modern scripts. Apart from letters from famous Dutch people, be they Erasmus, Anthoni van Leeuwenhoek, Rembrandt van Rijn, the brothers Vincent and Theo van Gogh, Anne Frank or Johan Cruyff, numerous letters stem from ordinary people. Letters by famous Dutch writers, often written when they were not yet famous, appear in many genres, even in the section for children’s letters.

With 34 genres Steinz created a wonderful array of moods and aims in letters, bringing emotions from love to hate, anger to happiness, obedience and protest into relief. Sea post, not unfamiliar here from the posts I wrote here about the letters among the Prize Papers in the collection of the High Court of Admiralty held at the National Archives, Kew, figures as the first genre. Letters by prisoneers and letters with threats, letters applying for a job and rejections by firms, letters from scholars and simple notes about household chores show many sides of human life. Steinz brings together letters from many Dutch cultural institutions. She dispensed with exact references to archival collections, thus making it into a nice exercise to trace these meta-data. Steinz redeems this omission with a substantial bibliography of relevant literature about Dutch letters.

Apart from letters captured by enemy navies Steinz used another curious collection of letters which never reached their destiny. Simon de Brienne, a seventeenth-century Dutch postmaster, retained some 2600 undeliverable letters in a chest. After nearly a century in the former Communication Museum, The Hague, these letters and the entire museum collection will move in September 2024 to the main location of Beeld en Geluid [Sound and Vision] in Hilversum, the Dutch national audiovisual museum. The chest and letters were the subject of the independent Brienne research project, now itself part of the international Letterlocking project for creating a typology of ways of sealing letters, and for tracing and reading unopened letters using new technologies. At Early Modern Letters Online (EMLO) you can find the catalogue of the letters within the Brienne collection and references to the research about them. It is touching to see in Steinz’ book letters of prisoners among these undelivered letters. Yet another lifeline had been locked for them.

In her foreword Steinz gave a place of honor to Francisco de Tassis (1459-1517), the founder of the first European postal service. I could not help remembering only the Thurn und Taxis family in Regensburg, but they are indeed connected with this man. I readily admit that when looking at Vanzieleghem’s blog I was surprised to read in an old French manual for legal history about the postal service of the university of Paris. Its monopoly ended in 1719. Vanzieleghem could not yet find the first royal ordinance issued in 1383 about the postal role of this university which from then on should serve each French diocese.

To me it seems definitely fitting the themes in this post are connected with each other in some way. It will do no harm to compare postal tariffs with printed itineraries. It is also clear spatial history needs a sure foundation on historical research. Letters and postal services vitally connected and connect people just as much as the internet does since a few decades. In Italian legge (laws) and leghe (miles) might look rather similar, and indeed they are not miles apart from each other. Legislation concerning letters and post deserves due attention from legal historians.

An addendum

A good starting point for researching Early Modern postal services is the chapter by Nikolaus Schobesberger et alii, ‘European postal networks’, in: News networks in early Modern Europe, Joad Raymond and Noah Moxham (eds.) (Leiden-Boston, 2016; online in open access) 19-63. This chapter suggests for example the inclusion of key postal stations in the Holy Roman Empire at certain moments can help to date the moment of creation of the contents in printed itineraries. It is good to see both this article and Midura point to Ottavio Codogno’s Nuouo itinerario delle poste per tutto il mondo (Milan 1608) as a very important source.

In the PDF version of the Munich copy of the Poste diverse the date of publication is still indicated as 1550. At p.15 it is also stated the emperor lived sometimes in Prague, altre volte vi abitava la Maestà Cesarea, referring either to the period in the fourteenth century or to the period between 1583 and 1620.