Approaching a subject in legal history can often start from very different points of departure. You might look at Frisian law as a typical branch of Dutch legal history, but it is equally possible to consider it a part of Scandinavian law. A new edition and English translation of an important text for Frisian medieval law, the Freeska Landriucht has recently been edited by Han Nijdam, Jan Hallebeek,and Hylkje de Jong [Frisian land law: A critical edition and translation of the Freeska Landriucht (Leiden-Boston, 2023]. This book in the series Medieval law and its practice (volume 33) is even available online in open access. In this contribution I will look at the text edition, the translation and also in particular at the important introduction offered by the editors. I will also look briefly at a new website presenting a number of manuscripts with Frisian legal texts.

Introducing Frisian law

The introduction by Han Nijdam, staff member at the Fryske Akademy in Leeuwarden, very soon points out the fact the Freeske Landriucht is a compilation of legal texts in Old Frisian. Therefore this edition and translation gain in importance. Nijdam succeeds in writing a very rich band relatively compact chapter, and I can hardly do full justice to it here. I can understand the clear wish for lucid presentation of the corpus of texts at this point, but somehow using only English titles might feel a bit strange. However, i conceed immediately my view is influenced by the volume Asega, is het dingtijd? De hoogtepunten van de Oudfriese tekstoverlevering [Asega, is it law time? The highlights of the Old Frisian text tradition], Oebele Vries and Dieneke Hempenius-van Dijk (eds.) (Leeuwarden-Utrecht, 2007) who presented a number of texts with apart from the Old Frisian original also translations into modern Frisian and Dutch. Anyway the prologue of the Freeske Landriucht gives the Frisian titles of the texts in this compilation (p. 88) .

Nijdam, a specialist of early medieval Frisian law, explains why a number of important terms such as asega, gretman and scelta defy attempts at unequivocal translation; these untranslated terms are listed in a glossary (p. 443) with clear indication of their mulitple connotations. Apart from a succinct discussion of each text he explains also the legal subjects touched by the various texts, and he looks at the influence of the church in Frisian law, too. Roman law and canon law, too, come into view. Editing and translating the text is complicated by a number of factors. Although the origin of the texts can be retraced to the thirteenth century the material sources used are much younger. For a number of texts there is a learned gloss in Latin. A preliminary collation of them by the late Hans Ankum and Klaas Fokkema proved to be invaluable, but even their ground work had to be checked and corrected at some points.

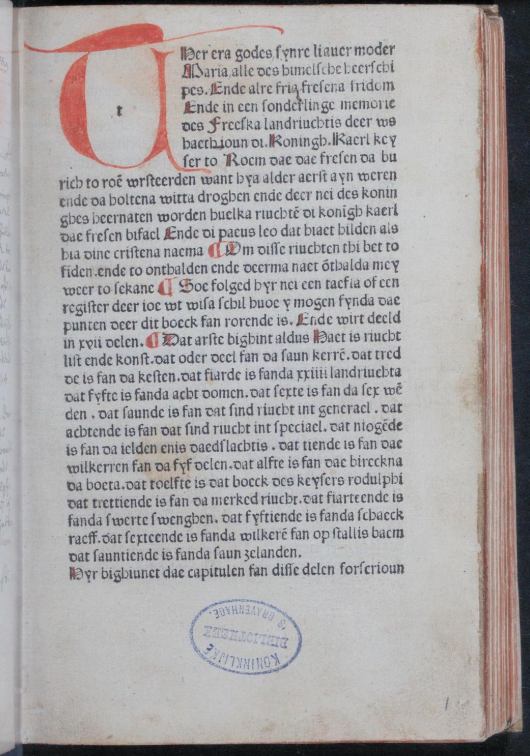

Translating the Latin of these glosses was yet another challenge for jan Hallebeek and Hylkje de Jong. Han Nijdam edited the main text. One of the most important sources for the Freeska Landriucht is an incunable edition, Dat aelde Freeska landriucht, dated in the Gesamtkatalog der Wiegendrucke around 1484 (GW M16942; nine copies extant,see also ISTC no. il00045500). The printer, location and date are not mentioned in this incunable. A veritable flood of publications over the centuries has brought many speculations and few solidly confirmed facts about its origin. The watermarks of the paper used for this work and five connected publications printed by the so-called Printer of the Freesk Landriucht have been dated in the period 1483 to 1486. The Pastei research group for Frisian book history recently conducted its own research on this subject, and I will come back to them in the section on Frisian legal manuscripts. In view of the variety of material sources, the influence of Early Modern Frisian historiography on scholarly study of Old Frisian law, and the nationalist bias of a number of scholars in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries Nijdam is to be applauded for steering a safe course and giving us a reliable overview of many matters.

Facing the variety of manuscripts and copies of the incunable edition that could be used the editors decided to take some resolute decisions. For the incunable they choose the copy of the Fries Genootschap, held at Tresoar in Leeuwarden, as their main source. Jan Hallebeek, formerly at the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, and his successor Hylkje de Jong, too, use the same copy for their edition of the glosses. They provide a concise presentation of the sources referred to in the 188 glosses. They conclude the glosses were compiled in the fourteenth century, the same period in which the compilation itself was probably created. Notwithstanding the fact Frisian legal manuscripts figure only around the text edition the editors do mention most of the important manuscripts. The bibliography (pp. 78-86) does lead you to modern editions of single legal texts using these manuscripts, and it provides you also with a good overview of relevant scholarly literature. For those wanting to focus on the glosses to a single Frisian legal text I can do scarcely better than point you to the online version of an article by Jan Hallebeek, ‘The Gloss to the Saunteen Kesta (Seventeen Statutes) of the Frisian Land Law’, Tijdschrift voor Rechtsgeschiedenis 87 (2019) 30-64. The importance and influence of Roman and canon law, especially for legal procedure, comes here into view, and he shows how the glosses help also to date the version of the main text more precisely.

In my view the introduction can serve as a very helpful nutshell guide to medieval Frisian law. Anyway, it helped me to get a much clearer picture of Frisian legislation. The sources in the Freeska Landriucht stem from central Frisia, roughly the modern Dutch provinces Friesland and Groningen, and they belong to an older period. From 1400 onwards the Excerpta legum / Jurisprudentia Frisica came into vigour, only to be abolished in 1498 when duke Albrecht of Saxonia came to rule central Frisia, making it a part of the Holy Roman Empire. This change in political power certainly influenced the later historiography about a legendary Frisian freedom. Nijdam stresses the fact the Old Frisian has been updated, and De Jong and Hallebeek noticed the glosses seem almost unchanged. With due attention to such matters and clear explications about them you may conclude that the edition has a sound foundation. The Frisian text is presented with the glosses immediately after the relevant section with the translation on the facing page.

Frankly I can say few things about the quality of the translations, but to me they seem reliable. The edition presents itself with a few footnotes. The integration of the glosses and their translation, with clear rendering of juridical allegations which can be traced in a separate index, are perhaps the most innovative feature, and no doubt also the source of more headaches to get things right. Both the introduction to the main text and the introduction to the glosses have been prepared with great care. In my view these introductions are a must-read for anyone wanting to explore the fields of medieval Frisian law. With this many-sided book Hylkje de Jong, Jan Hallebeek and Han Nijdam perform a tremendous service to legal historians and to all scholars interested in medieval Frisian history.

Frisian law in context: The manuscripts

The texts in the edition of the Frisian Land Law are not all on the same level. The twenty-one texts start with a prologue indicating the contents, and the very last text, atreatise on the Seven Sealands (pp. 438-441), is a short treatise on Frisian political geography. Frisian regions were found between the river Schelde and the Weser in Germany. The four maps help you to pinpoint the regions mostly dealt with in the various texts. One of the strengths of the introduction by Nijdam is the fact it covers the entire medieval period, and it can serve indeed to guide your steps in dealing with the oldest legal texts and manuscripts from Frisia.

By the way, the Lex Frisionum, a legal text in Latin created around 800, is much older than those texts in Old Frisian. I am happy to refer you to the overview for the Lex Frisionum at the website of the Bibliotheca legum project led by Karl Ubl in Cologne. For the Lex Frisionum a printed edition from 1557 is the first surviving textual witness.

By a lucky coincidence two new online platforms recently appeared with a prominent place for Frisian law. It is only logical to look at them here, too. Tresoar, the combined provincial archive and library of Friesland in Leeuwarden, holds a number of Frisian legal manuscripts. After a long period of preparation the digitized versions of these manuscripts finally became available online on a new subdomain for its digital collections, however not as prominent as these manuscripts deserve, just as items of the small general digital library.

Therefore Tresoar decided to presenr the ten (!) manuscripts on a special website, called the Richthofenkolleksje. The website is accessible in Dutch and Frisian. The ten manuscripts originated between 1400 and 1600. Several scholars once owned one or more of them, but finally all manuscripts – and a copy of the incunable edition – were bought by Petrus Wierdsma (1729-1811), who published with Pieter Brantsma two volumes of Oude Friesche Wetten (Kampen-Leeuwarden, [1783-1788]; online, Google / Utrecht University Library) with a Dutch translation. After much trouble with the Frisian scholar Montanus Hettema Karl von Richthofen (1811-1888) succeeded in 1858 in buying them from Wierdsma’s family. In 1922 the manuscripts returned from Breslau (now Wroclaw) to Leeuwarden. Von Richthofen had studied with Karl Friedrich Eichhorn and Jacob Grimm. Directly after his main work on Friesische Rechtsquellen (Berlin, 1840; online, Internet Archive) Richthofen published also an Altfriesisches Wörterbuch (Göttingen, 1840; online, Internet Archive). The Richthofen website offers a brief overview of the manuscripts, a timeline of research and the whereabouts of the manuscripts, and it presents educational programs on Frisian (legal) history for children in primary and secondary schools. Surely the recognition of the importance of these manuscripts and the homecoming a century ago was crowned by admission in 2022 to the UNESCO Memory of the World Register by its Dutch committee.

New research on these manuscripts at Leeuwarden has recently been done by Riemer Janssen, Anne Tjerk Popkema and Herre de Vries, directors and members of the Pastei research group for Frisian book history. The three researchers studied both the manuscripts and the incunable with the Freeske Landriucht and the riddle of the unknown printer and his publications. In the publication corner of the Pastei website, the Bibliotheca Pasteiensis, you can find the report on the ten manuscripts in the Richthofen collection (in Dutch). Their new descriptions of the ten manuscripts is also present at the Richthofen website, as is a report on their material condition. What Nijdam writes about Frisian legal manuscripts is important as a fair status quaestionis (pp. 14-17). Nijdam’s overview of texts place them in groups in chronological order which differs considerably from the order in the Freeska Landriucht.

Interestingly medieval manuscripts held at Tresoar in Leeuwarden, figure promintnely at the beta version of the new portal e-CodicesNL for medieval manuscripts in Dutch collections. This project will become the successor to Medieval Manuscripts in Dutch Collections (MMDC). At the new platform created by the Huygens Institute in Amsterdam and launched in March 2023 you will find currently digitized manuscripts from Tresoar, the Athenaeumbibliotheek, Deventer, and the Huis van het Boek (formerly Museum Meermanno-Westreenianum), The Hague.

The proof of the pudding is of course comparing the current descriptions at eCodicesNL, the MMDC portal, at the two websites created by Tresoar and the new descriptions offered by the Pastei research workgroup. For this purpose I choose at will the very first Richthofen manuscript (Leeuwarden, Tresoar, PBF, Hs R1) with the Emsinger Landrecht. The description at eCodicesNL gives the full provenance since Ernst Friedrich von Wicht in the sixteenth century. You can choose between a succinct overview and a full description with information about the incipit, layout and decoration, provenance and acquisition. The field for bibliography is still empty. The manuscript with the Emsinger Landrecht, an East Frisian law from 1312, can be viewed with the IIIF viewer, with some additional information, in particular on the language, stated as Western Frisian. The binding is described in the overview as medieval. At MMDC you will find just one coloured image, but there are two references to scholarly literature, and also the nickname and siglum of this manuscript, the Derde Emsinger handschrift (“E3”).

The website for the Richthofenkolleksje gives the name, the signature and siglum of the manuscript, the date of the single text, without a date for the manuscript itself. The page on the manuscripts does lead you to the two reports by the Pastei group. The description in the Pastei report runs for twelve pages. The language is determined as Oosterlauwers Fries, East Frisian, which seems more probalble than Western Frisian; I suppose there is just a typing mistake at eCodicesNL. The binding is dated in the late eighteenth century. The provenance at eCodicesNL stems from this report which states the fact it is only a summary of a publication by a group member. In this report the content of the Emsinger Landrecht is meticulously described in its consisting parts.

In the digital library of Tresoar one is referred for information about the contents to the manuscript catalogue edited by Jacob van Sluis, Inventaris van de handschriften van de voormalige Provinsjale Biblioteek fan Fryslân (Ljouwert, 2007), online in this digital library. Van Sluis devotes just two pages to the ten Richthofen manuscripts (pp. 406-407), with some key references to editions and scholarly literature but omitting dimensions and the number of folios, evidently a decision taken in view of the sheer mass of other manuscripts to be described in this summary manuscript catalogue. The digital library of Tresoar, too, refers you for the ten legal manuscripts to the reports of the Pastei research group for full information. Hopefully the educational material of the Richthofen website uses the chance to tell children and students something about medieval book production, Frisian law or material subjects around the manuscipts. Already a single extra page on one of these themes would make this website more substantial.

My first impression after just checking just one example is that you can use both eCodicesNL and MMDC for finding a reliable concise codicological description, and with its access to digitized manuscripts eCodicesNL scores clearly. The Richthofen website and the digital library of Tresoar point you to the reports created by the members of Pastei for very full descriptions meriting close attention. The staff of the eCodicesNL project, Irene van Renswoude, Renée Schilling and Mariken Teeuwen, clearly states the fact that their three-year project (2020-2023) is still incomplete, notably for bibliographical references and digitized manuscripts yet to be uploaded and description to be added. Most of the current descriptions stem from the MMDC portal. The XML-TEI data are not yet publicly available, and DOI’s have to be added to each item. 180 out of 205 digitized manuscripts for the pilot project are now online. By choosing the Swiss e-codices platform as its model, even frankly as best practice to be followed, the team of eCodicesNL sets its aim high and hopes to find funding for a sequel to attain to a full extent the high quality level it strives for.

Paths to be discovered and pursued

At the end of a rather long post showing various sides of current research on and access to Frisian legal sources it is clear these resources help you very much to delve into them and use them for widening your view of both Frisian, German and Scandinavian medieval law. In a post on Nordic manuscripts and inscriptions with runes I presented some of the online resources for Scandinavian medieval laws, and in another post I looked at translations of Scandinavian laws from the Middle Ages and projects for other languages. These posts are already a bit older, from 2011 and 2016, and this makes me happier to mention here the project Voices of Law: Languages, Text and Practice which I detected only when finishing this contribution. Translators of medieval legal texts face multiple challenges just as much as editors do. De Jong, Hallebeek and Nijdam did not start from scratch, but I was really surprised they offer their translations, too. May their volume serve as a bridge and an invitation for closer cooperation between translators, and of course also as a spur to integrate medieval Frisian laws when comparing Scandinavian and other legislation from the northern part of medieval Europe!

A postscript

The Athenaeumbibliotheek in Deventer presents its digital collections – with manuscripts, printed books, maps and a database on printers in Deventer – on a separate platform, Athenaeum Collecties. The Huis van het Boek in The Hague presents under the heading Collecties Online only its online catalogue. Digitized illuminated medieval manuscripts of this museum can be found at the shared platform of the Dutch Royal Library for this genre. Currently 69 manuscripts from The Hague, 59 from Deventer and 52 from Leeuwarden are online at eCodicesNL.