Every now and then you encounter on the web projects and initiatives you simply want to share with others. Today I noticed the blog of a project around illuminated French charters. The long bilingual title says a lot: Macht, Diplomatie und Dekor – Pouvoir et diplomatie par l‘enluminure. Die illuminierte Urkunde in Frankreich – Les chartes enluminées en France 1160 – ca. 1420. For shortness‘ sake the blog luckily has the concise name Carta Franca! The blog accompanies the project on Macht und Diplomatie, power and diplomacy of Gabriele Bartz and Jonathan Dumont at the Institut für Mittelalterforschung of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna. The objects at the centre of this project can be viewed online at Monasterium.net as a subsection of a larger section with illuminated medieval charters at this portal, a result from the project at the university of Graz. What does illumination mean as an element of acts written on parchment? How come art history and the history of diplomacy, diplomatics and legal history together? In this contribution I like to put the spotlight on thees questions.

Multiple perspectives

My curiosity for the subject of this post comes not only from my interest in legal iconography and medieval history. As a student I completed almost a minor in medieval art history. The riches of the library for art history at Utrecht University and the presence of a copy of the famous Index of Christian Art helped to develop my interests in this field.

Medieval charters show always to some extent power, first of all the power to document acts by writing, by creating a document and by authenticating it with a sign, in particular with seals. In 2019 I wrote here about the visual power of seals, and seals figured also in my 2019 post on digital approaches to medieval charters.

At Carta Franca art history and diplomatics are the main focus. Since 2020 five contributions take art history as their starting point. Really spectacular is the recent post by Gabriele Bartz – in German – concerning a royal charter from 1332 showing both the heads of king Philippe VI (reigned 1328-1350) and his wife Jeanne de Bourgogne in the illuminated double initial, the first two letters of the charter. In this act the king changed his marriage gift to the queen, because he had decided to destine his original gift for her to his son. Bartz compares this charter with some contemporary examples and tries to establishes a link with known illuminators in this period. At Monasterium this charter is presented with a summary of the contents, a description, a commentary and bibliographical references.

Surprising in this category is also the contribution focusing on the decoration of the plica, the small folded lower part of a charter to which seals are attached. Even historians do not always look carefully at a plica in order to check for any chancery marks or remarks. Sometimes scribes scribbled knots, others turned circles into faces, yet another draw eyes on both sides of the threads connecting the seal to the charter. Bartz views these drawings as an innovation of the mid-fourteenth century. Both contributions show a judicious balance between art history and other historical disciplines.

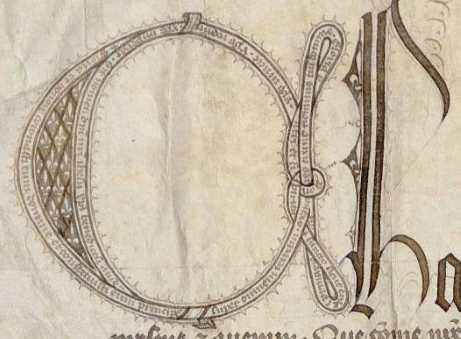

The category Diplomatik / Diplomatique – to be distinguished from Diplomatie, diplomacy! – contains currently just one contribution in French by Jonathan Dumont, La foi au secours du droit, faith helping the law. A charter of king Charles V from 1372 is illuminated with a large initial C at the beginning. To the drawing lines from three psalms have been added [Ps. 7 (8),7, Ps. 45 (46),16-17 and Ps. 112 (113),2], and also the title of the Easter hymn Christus vincit, Christus regnat. In this charter Charles V confirmed the last will of his deceased brother Louis d‘Anjou and instructed his officials not to interfere with the execution of its stipulations. Dumont places the words in the realm of transcendental representation of kings and royal power, and he nicely notes also this act runs against normal law calling for diligence with last wills. For Dumont it is also a matter of dynastic power at work in favour of his late brother. This charter, too, is fully commented at the Monasterium charter portal. Of course this single contribution wets the appetite for more posts from the perspective of diplomatics and legal history.

Charters in context

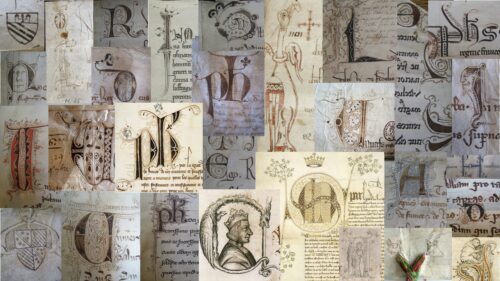

The project in Vienna started in August 2020 and will run until 2023. Not only royal charters will come into view. Bishops and monasteries, too, issued illuminated charters. The projected corpus of some 1,300 charters will become visible at Monasterium. Within its general section for illuminated charters there are currently six subcollections, not only for France, but also for the most splendid examples, called Cimelia (sometimes called Prunkurkunden), charters from Lombardy and papal charters. There is also a glossary in German for the terms used in describing illuminated charters. By the way, the Monasterium portal has a multilingual interface, but not every element has been translated.

In fact there are even more similar collections at Monasterium. The collection or subset with French illuminated charters has only been added on December 2, 2021. Thus it is certainly useful to check the list of recent additions at Monasterium. As for now the collection overview shows thirteen collections with illuminated charters. The portal contains now contains information about and often also images for charters from nearly 200 archives in fifteen European countries. You can approach the 660,000 charters included currently by archival collection and by research collection or through an index search. The Monasterium portal has developed into a major resource for research concerning medieval charters. The section for illuminated charters is the fruit of the project in Graz led by Martin Roland, Georg Vogeler and Andreas Zajic.

The medium is the message

The research into the existence, form and role of late medieval illuminated charters can help to view charters differently. Not only the legal act transmitted in a charter is important. Its importance can be expressed more convincingly and visible by using illumination and illustration. More precisely, these added elements can highlight other messages not spelled out in the text of the charter. The illumination of charters adds a second layer of information, operating on another level of action and perception, sometimes showing simply the richness of the issuing person, sometimes highlighting an aspect of his power or showing the intent to put this power in a particular light.

Following the progress of the Carta Franca project in Vienna is helped by the blog and its Twitter account @Cartafranca1. A project website is often static or just a part of larger portal, and even so often project results appear elsewhere. Publications in print from the contributors to these projects on illuminated charters have of course appeared, too. To mention just some examples, Martin Roland contributed the article ‘Illuminierte Urkunden. Bildmedium und Performanz‘ to the essay volume Die Urkunde: Text – Bild – Objekt, Andrea Steildorf (ed.) (Berlin 2019). Gabriele Bartz and Markus Gneiss edited the volume Illuminierte Urkunden. Beiträge aus Diplomatik, Kunstgeschichte und Digital Humanities (Cologne-Weimar-Vienna 2018; Archiv für Diplomatik, Schriftgeschichte, Siegel- und Wappenkunde, Beiheft 16). The project in Vienna follows after research projects about illuminated medieval manuscripts in Central Europe. The connection with manuscript production is just one of the perspectives helping to study the subject of illuminated charters. In the brief compass of this contribution I hope to have made you curious, too, about new ways to study a classic source genre for medieval history and some of the tools making such research possible.