Archaeologists and historians in general do things differently. Archaeologists search and interpret material objects and traces of human history hidden from sight in the soil, and historians look at still existing documentary evidence, be they written documents or artefacts above ground level. Thus the title of the digital project The Documentary Archaeology of Late Medieval Europe (DALME) created at Harvard University is at least intriguing. The core and clue of this projects are written documents telling us about objects sometimes no longer existing which offer a glimpse of medieval households.

Without twisting the evidence of these inventories you can view a number of them as the results of actions required by law or statutes. In this post I want to highlight these legal dimensions and look at the qualities of the DALME project which has been awarded the 2022 Digital Humanities and Multimedia Studies Prize of the Medieval Academy of America.

Precious traces of material surroundings

Many scholars are involved with this project, both at Harvard and elsewhere. The project is led by Daniel Lord Smail, Gabriel Pizzorno and Laura Morreale. The principal objective of the DALME project is to bring together both inventories in the holdings of archives and objects nowadays kept by museums. The project aims also at developing a common vocabulary and a digital infrastructure facilitating research from various disciplines. The inventories and objects can be approached in several ways and will be accompanied by essays. Until now only three essays have been published at the project website. The latest essay by Marcus Tomaszewski published in January 2022 looks at a German tradition of poems with inventories. Laura Morreale looked in her 2020 essay on enslaved persons in fourteenth-century Florence. In the general overview much stress is put on the difficulties of reading and deciphering medieval scripts and languages, but this is not an unique feature for studying medieval history. Classicists dealing with for example the Near East face similar obstacles.

The introduction to the methodology of the DALME project stresses a kind of material turn that has influenced scholars in many disciplines in the past decades. Inventories are much valued as a window on daily life. Objects are every bit as important to tell us the history of humanity as written sources. It seems logical to bring them together to enhance making relevant comparisons of material life and circumstances.

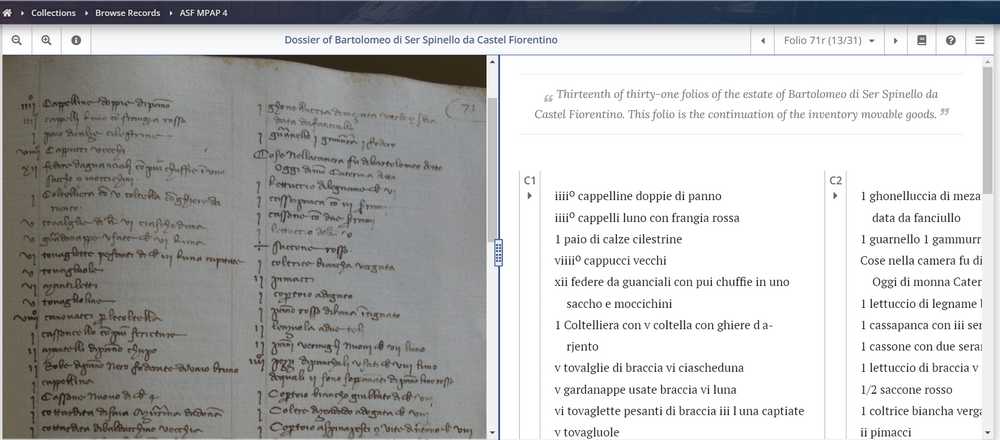

It is important, too, to have a look also at the DALME workflow for inventories. Before images of documents gain their final form in the system behind DALME a lot of steps are to be set. These images are used to create transcriptions and to provide annotation. The information thus created is subsequently parsed and re-encoded. For creating a uniform and searchable terminology the Art and Architecture Thesaurus (AAT) of The Getty is used.

One should not overlook the section with project publications nor the bibliography pointing to source editions, scholarly literature, glossaries and dictionaries and other relevant publications, often with links to digital versions. Links becomes only visible when your cursor arrives at them. Obviously the study of Daniel Lord Smail, Legal plunder. Households and debt collection in late medieval Europe (Cambridge, MA, 2016) has stimulated the creation of the DALME project; incidentally, you can view the bibliography for this book online. There is no section with general online resources, and thus the name of Joseph Byrne and his online bibliography of medieval and Early Modern wills and probate inventories is missing. Byrne points for example to a number of articles by Martin Bertram published in the journal Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen Archiven und Bibliotheken (QFIAB) and in other journals on testaments from Bologna. Issues from 1958 onwards of QFIAB can be seen online at the Perspectivia portal. Among general resources for tracing relevant literature and editions the online bibliography for medieval studies of the Regesta Imperii in Mainz, and the Online Medieval Sources Bibliography should take their rightful place. The latter has even a preset filter for material culture. A recent article by R.C. Allen and R.W. Unger about their Global Commodities Prices Database is mentioned, but there is no link to their database. It is good to see the work of Daniel Williman and Karen Corsano, The spoils of the Pope and the pirates, 1357: the complete legal dossier from the Vatican Archives (2nd edition, 2014) has been included.

Eight collections of inventories

I had honestly thought my remarks about the bibliography of the DALME project would form my last grumbles in this post, but when you choose in the Features menu for objects you will find just a few objects discussed in sometimes very short essays. Maybe this section will be enlarged soon, but now it is still nearly empty.

The Collections section brings you to eight collections. You can search or browse them. Both options come with very practical filters. In the browsing mode you can use a filter for record type showing you graphically all kinds of legal documents and the various genres of inventories. When you choose to explore the collections you can navigate an interactive map of Europe. DALME brings you at this moment nearly 500 records.

Two collections show immediately in the title their legal nature, 58 records for Florentine wards (1381-1393) and insolvent households in Bologna (1285-1299) with 41 records. The section with ecclesiastical inventories focuses currently on French priests and canons. It will contain in the near future inventories from some well-known cathedrals and monasteries. DALME shows its strength in particular in presenting 50 Jewish inventories from France, Germany and Spain, a rare resource. Tax seizures, inquests into crimes and notarial acts or services formed the legal ground to create these records. Apart from a collection focusing on records from cities in Northern Lombardy, from Marseille and the region around this town, with 168 records the largest collection, there is a collection for the States of Savoy (24 records) and a miscellaneous collection, good for 121 records. Each collection comes with a general introduction, a section on its goals and objectives, explanations about the sample, some highlights and information about the intellectual owner of and contributors to a particular DALME collection.

In a second section with four categories you can approach partial and fragmentary lists created for seizures, estimates, sales and tariffs. Currently only a small number of sales and estimates can be viewed.

For my own pleasure I searched in Dutch online resources for an inventory made in 1297 of goods found at the convent of the Hospitaller Knights of St. John in Utrecht and transferred to a canon of the Oudmunster collegiate chapter and Jan van Duvenvoorde. The inventory in this charter has been identified as a list of goods belonging to count Floris V of Holland who had stayed there in Utrecht just before he was killed near Muiderberg on June 27, 1296. You can find editions of the charter in the Oorkondenboek van het Sticht Utrecht tot 1301 (1297 April 6, OSU V, no. 2812) and the Oorkondenboek van Holland en Zeeland tot 1299 (OHZ V, no. 3268). The presence of chivalric cloths, many gloves and silver objects is indeed telling. Alas the original of this charter no longer exists, but seventeenth-century copies of it have survived.

Some early impressions

When searching inventories at DALME a few things become clear. You can currently only find items in their original languages or when they are mentioned in the record description, and not yet using the promised thesaurus function. In my view a major feature is thus currently not yet present. There is a difference between records taken directly from archival sources and those taken over from existing editions. In some cases a part of a document has not been transcribed because it does not contain a part of the proper household inventory. For the document shown here above with 31 folia this restriction is most sensible.

To be honest, I feel a bit baffled by the laurels given to this project in this stage. In my view the report about the 2022 DHMS Award shows a cavalier attitude to some of the clear deficiencies and missing qualities of DALME in its current state. Of course I can see that bringing together documents in twelve languages, providing images and transcriptions and commentaries is surely a feat. Creating 500 records in one year is not a particularly large number. DALME does aim at open access and easy interoperability, but the report states it is still unclear whether third-party software can harvest directly from DALME. The use of TEI for encoding the records and Zotero for the bibliography is commendable, but why create your own remix of tools for the management systems behind the screens? At GitHub you can find the necessary technical information about the databases of DALME and the mix of tools applied for it, but no direct link is given to the bibliography at Zotero. For all its qualities Zotero is notably weak when it comes to actually finding a group library within it. The twelve languages do not return in the choice of glossaries and dictionaries in the DALME bibliography.

DALME’s relatively low number of records for inventories, the very low number of objects and the lack of integration between them, are quite visible. Add to this the uncertainty about reuse and the absence of a fundamental essay on the legal nature of many documents, and you have grounds for reasonable doubts about the core qualities of this digital project. For some collections you find more or less detailed information about the kind of legal documents, but as for now there are no general essays introducing the various source genres. Contributions by legal historians would here be most welcome.

Let’s for a moment turn away from DALME and look more generally at criteria and standards for evaluating digital projects. A few years ago the Medieval Academy of America developed a serious basic set of standards for its database Medieval Digital Resources (MDR), discussed here in 2019. For viewing images the use of a standard such as IIIF is recommended, but this has not been used at DALME. However, its images are at least zoomable. Luckily, DALME seems otherwise compliant with the MAA’s standards advocated at its database and guide for medieval digital resources. By the way, I could not help using MDR to search quickly for other projects concerning material culture. Using the preset filter for this subject I could only view the first page of the results; going to the next page ended at an empty search form. MDR does contain numerous online dictionaries and bibliographies. A number of them has been included in the DALME bibliography.

The DALME project comes with high aims based on sound research. I truly expected 3D images of objects or at least integration with one museum catalogue for medieval objects or a portal for archaeological objects, such as Portable Antiquities Netherlands. A year after its launch some wishes to make DALME outstanding could perhaps have been already fulfilled. I could not help noticing that for example the collections from Florence and Bologna are a century apart of each other, and thus comparisons are not as straightforward as possible, even though such comparisons remain challenging. As for the Florentine documents, a choice from the early fifteenth century would have invited a comparison with data in the Online Catasto for 1427-1429, created by the late David Herlihy and Christiane Klapisch-Zuber, and hosted at Brown University. It is reassuring to find a helpful table with some suggested equivalent terms in various languages and a clear list of online dictionaries in the classroom section. In an upcoming seminar Laura Morreale (Georgetown University) will focus on editing and transcribing Florentine documents.

How does this project compare to similar projects elsewhere? I looked briefly at the BoschDoc portal for documents concerning the Dutch painter Jheronimus Bosch. Its search possibilities are impressive. Some eighty inventories have been included, many of them with images, transcriptions, translations and references to relevant literature. The background information, in particular for technical matters, is much more restricted than for DALME, but it does contain a useful list of transcription criteria. The difficulty of scripts and languages is bewailed at DALME, but the actual approach to overcome them is not made completely explicit nor are solutions actually implemented or visible. Hopefully Laura Morreale and her colleagues can quickly add their set of transcription criteria to DALME.

The fact I devoted a rather lengthy review to DALME indicates indeed my opinion that in the end we can welcome a valuable resource for medieval historians at large. Its flaws have to be redeemed, but they help in a way to view similar projects much clearer. I must add that navigating the menus for background information was not as easy as using the collections themselves. The larger essays at DALME are certainly worth your attention and wet the appetite for more. I would be hard pressed to determine whether DALME is a pilot project or a project in its beta phase. In my view DALME is not yet a convincing winner of the DHMS award. Despite all drawbacks Smail, Pizzorno and Morreale deserve praise for their initiative, as do the other scholars who worked hard to provide images, transcriptions and additional information. This international project brings us for now a kind of showcase of what can become a resource not just to use for your own goals, but to discuss with historians from other disciplines as an exercise in rethinking your approaches to medieval documents and objects. The lacks and omissions at DALME should help you to raise your own standards, to apply standards for data exchange with other resources, and to reflect on the use of evaluation standards for digital projects.

Some afterthoughts

After publishing this post I quickly realized some additions might be helpful. A fine example of an image database for medieval and Early Modern material culture is REALonline of the Institut für Realienkunde des Mittelalters und der frühen Neuzeit (IMAREAL) in Krems an der Donau. In its journal Medieval and Early Modern Material Culture Online (MEMO) the issue no. 7 (December 2020) was devoted to the theme “Textual Thingness”. In this issue the article by Christina Antenhofer, ‘Inventories as Material and Textual Sources for Late Medieval and Early Modern Social, Gender and Cultural History (14th-16th centuries)’, MEMO 7 (2020) 22-46, provides you among other things with a brief discussion of the various forms and (legal) origins of inventories. She mentions the entry for inventories in a German dictionary for legal history by Ruth Mohrmann, ‘Inventar’, in: Handwörterbuch zur deutschen Rechtsgeschichte II (2nd ed. Berlin 2012), cc. 1284–1285.

At a few moments since writing this post I checked the database Medieval Digital Resources (MDR) and its browse and search functions to find projects about material culture. The snag with both functions of not being able to proceed from a first page with results remains, but at last I saw in September 2023 you can avoid irritation about this still unsolved bug in certain cases, and luckily this is the case for tags used for resources such as material culture. The successive results pages for individual are shown correctly. However, this particular tag only seldom bears directly at MDR to resources connected truly with existing medieval artefacts. MDR does indeed distinguish carefully between material culture as a subject heading, and material evidence as a general source genre. The true bug lies more in the inconsistent use of tags without a clear classification scheme with sufficient levels, a taxonomy or thesaurus.