The freedom of bloggers is not something you should take for granted. In some countries of the world blogging is really dangerous because governments are not at all at ease about the freedom to express oneself. 250 years ago Sweden saw the first legislation for freedom of print. In Sweden and Finland special websites gave been launched to celebrate this commemoration. Anders Chydenius, the Swedish minister responsible for the epoch-making law, came from Finland. In this post I would like to look at the celebrations and at eighteenth-century Sweden and the impact of this act of legislation.

The freedom of bloggers is not something you should take for granted. In some countries of the world blogging is really dangerous because governments are not at all at ease about the freedom to express oneself. 250 years ago Sweden saw the first legislation for freedom of print. In Sweden and Finland special websites gave been launched to celebrate this commemoration. Anders Chydenius, the Swedish minister responsible for the epoch-making law, came from Finland. In this post I would like to look at the celebrations and at eighteenth-century Sweden and the impact of this act of legislation.

A long history

The commemoration website Frittord 250 [The Free Word 250] created by the Swedish Academy of Sciences is the first point of access to find out about the law of 1766. The corner with source materials (Källmaterial & resurser) is the only point where you will find information about the historical legislation. You can download a PDF with a digital version of the original law (24 MB) or read it online at the website of the university library in Lund. With fifteen articles in a few pages it is a remarkable concise law. However, this evidentially led rather quickly to changes. Before 1800 there were already five new laws dealing with the freedom of print. The section offers the texts of seventeen ordinances and laws up to 2001. When you press the button In English you will find only a brief summary of the matter at the center of the commemoration. The calendar of activities and blog posts form the major part of the project website. One of the activities is a travelling exhibition Ordets akt [The act of the word], now at the Kulturhuset Stadsteatern in Stockholm.

Saying the focus of Frittord 250 is on the present is an understatement. I happened to find at The Constitution Unit website of University College London in the foreign corner of the section Freedom of Information an introduction about the Swedish freedom of press. Here, too, the story jumps from just one short paragraph about the original law to the current state of affairs. It is one thing to acknowledge the importance of current debates about freedom of speech, freedom of information and the way governments try to interfere with the public sphere, it is another thing to study developments and backgrounds which could be rather important in understanding and interpreting contemporary issues. For the United Kingdom the website of the Constitution Unit gives you at least a short history of developments since the sixties. The links section brings you for example to the international portal Right2Info where you can find much more. Its resources section is very impressive, even when you might wonder whether it is sufficient to mention for some countries only the national ombudsman.

The historical background of the 1766 law gets more space and attention at the Finnish website Freedom of Information: Anders Chydenius 250 years, a website accessible as often is the case in Finland in Finnish, Swedish and English. It is invigorating to read here about the historical, cultural and political background of Sweden’s pioneering law. Chydenius can be termed a very active exponent and propagator of Enlightenment ideas. His plea for freedom of press was part of his campaign in 1765 and 1766 for free trading rights. Maren Jonasson and Perti Hyttinen translated a number of Chydenius’ works in English [Anticipating The Wealth of Nations. The selected works of Anders Chydenius, 1723-1809 (London, etc., 2011)]. This book contains also a translation of the 1766 law. When preparing this post I also visited the website on copyright history of Karl-Erik Tallmo who looks not only at Sweden, but also at the history of copyright in England and Germany. Bournemouth University and University of Cambridge have created the well-known portal Primary Sources on Copyright (1450-1900), and you can also learn something from the digitized texts in the Archivio Marini (Università degli Studi di Pisa).

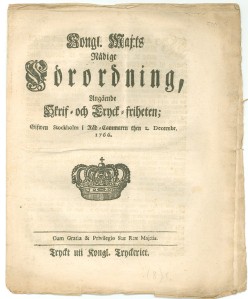

Instead of only looking at the context of this law we might as well look at this piece of legislation in some detail to establish the width of its impact on information. The law’s full title Kongl. Maj:ts Nådige Förordning, Angående Skrif- och Tryck-friheten, “His Majesty’s Gracious Ordinance Relating to Freedom of Writing and of the Press”, promises much. In the preamble censorship is nominally abolished but technically transferred to the royal chancery. The stress on the benefit for the enlightenment of the people and the observance of laws is remarkable. In the first article a clear limit for the freedom of expression is posed by forbidding anything that goes against the Christian faith. Writings criticising the form of the state and the king himself are prohibited in the second and third article. Publications have to be printed with full names or with the printer’s responsibility to disclose the author’s name. The need for due process in cases in which this is disputed is made explicit. The fifth article stresses the fact only the limitations of the three first articles can set a limit to any expression in print. The following articles deal with matters we would describe today as freedom of information, in particular concerning actions of the government and the judiciary, including the verdicts of judges. The support in the fifth and twelfth article for those wanting to write honestly and correctly about history is not only pleasing for historians, but indeed important. Article 13 is a clause to ensure any subject not included or mentioned falls under the freedom of press, and article 14 expresses the wish to make this law irrevocable. In my view this law can stand scrutiny from modern perspectives in a number of aspects. The law was issued on December 2, 1766. For Chydenius freedom was a crucial element in all his plans for reform and renewal of contemporary Sweden.

The Finnish website shows how exactly this wish for perennial and unchanged force was soon thwarted. It makes abundantly clear that the Swedish road was not a linear road of and to freedom of speech, print and information. Alas for those wanting things to be entirely black or white, good or bad, a success or a failure, the Swedish story shows history does not fit into their dualistic world view. Thus history can be perceived as a possible nuisance, a luxury good of elites or something a nation cannot afford anymore. I feel ashamed to live in a country where we have to face the threat of the disappearance of history as a part of the secondary school curriculum . Baron Raoul van Caenegem, the famous Flemish legal historian, wrote already many years ago: “Who hinders, forbids or abolishes the study of history, condemns people to ignorance and gullibility”.

It is up to you to look at both the Swedish and the Finnish websites, and also to the website of the Anders Chydenius Foundation, yet another example of a trilingual site, to expand your knowledge, deepen your understanding, in short to use your critical faculties to see the values history can provide and the ways it can sharpen our understanding of contemporary society. However, history can be more than a handmaiden guiding you to act wisely in current affairs, it can teach you much about women and men in the past, the ways they faced the problems of their times and aspired to be as much human as we do.