A few months ago already I spotted the beautiful catalogue Hieroglyphs. Unlocking ancient Egypt for the exhibition with this name at the British Museum (13 October 2022-19 February 2023). My initial interest was the palaeographical side of hieroglyphs. In 1822 Jean-François Champollion famously announced his decipherment of this script. One of the great merits of the exhibition is showing not only the Rosetta Stone as crucial to this breakthrough, but a combination of his own stamina and intellectual creativity, the comparison of several sources, languages and scripts, and not in the least cooperation with many people in Europe, Britain and Egypt. The exhibition traces in fact the development of what we now know as Egyptology from the Middle Ages to the present. I will not forget to look at legal sources in this fascinating story of philological work, the acquisition of cultural heritage by European countries and the challenges of Egyptology in our days. By choosing Egypt as a subject I follow my tradition of starting a new year with a contribution about an empire or imperial laws.

A story spanning centuries

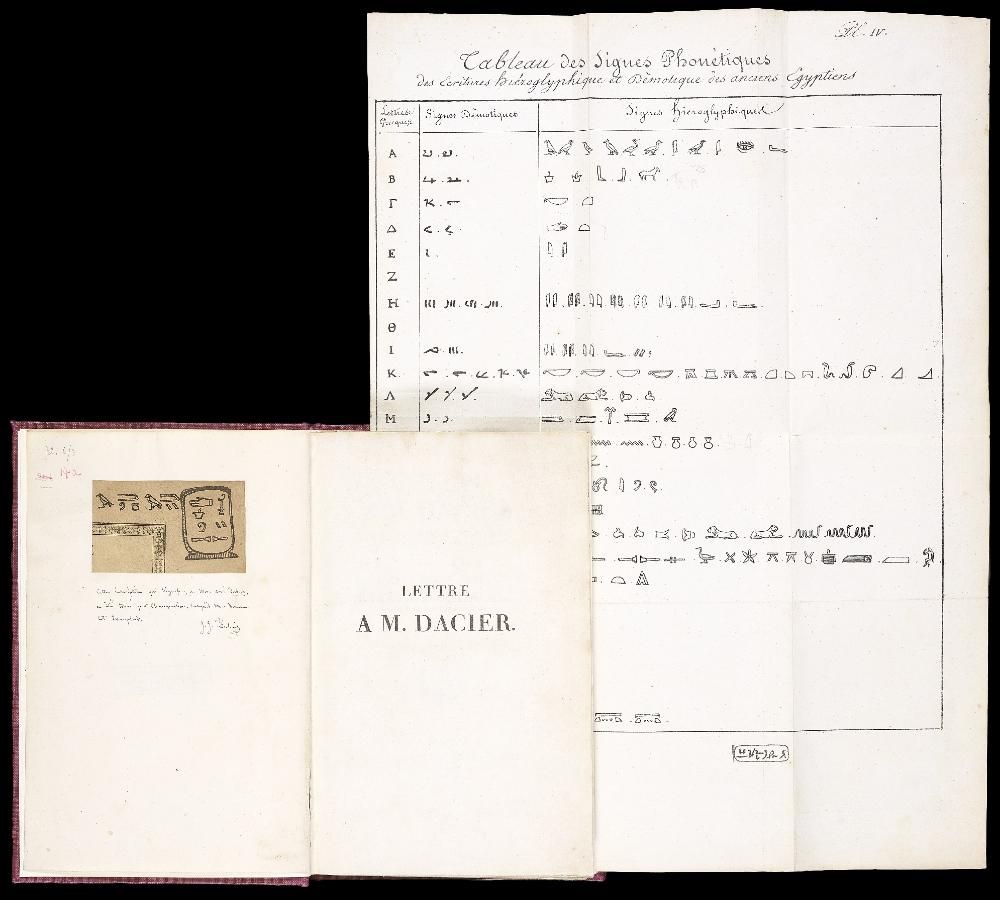

My own encounters with hieroglyphs did not start at the British Museum in 1980 and admiring the Rosetta Stone, but already earlier on. In 1976 I saw a copy of the Rosetta Stone in the municipal museum of Figeac, Champollion’s place of birth. He was truly one of the few heroes in philology from the nineteenth century, next to scholars such as the Grimm brothers and Wilhelm von Humboldt. The exhibition catalogue does not start with the heroic struggle between Thomas Young and Champollion, but takes you first to the fascination for Egypt that started much earlier. The first chapter of the exhibition catalogue, edited and largely written by Ilona Regulski, is aptly called ‘The truth in translation’. She charts attempts at decipherment from medieval Islamic scholars upto 1835, the age of the European vogue of collecting Egyptian antiquities at all costs by governments, tourists, museums and scholars. Regulski opens the catalogue with an introduction to the aims of the exhibition, followed by a lucid and concise explanation of the writing system in the hieroglyphs by Pascal Vernus. The crucial features of hieroglyphs are the combined use of both logograms representing concepts and actual objects on one hand, and using ideograms for phonetic representation on the other hand. This combination worked for centuries as a code which proved very hard to crack.

The second chapter describes the almost legendary race to decipherment led by Thomas Young (1773-1829) and Champollion (1790-1832) accelerated by the finding of the Rosetta Stone in 1799. Regulski shows that both men were only occasionly the archetypical chauvinist enemies so often depicted. Far more important were their individual choices to prefer at some point hieratic, demotic or Coptic script as the main road to understanding. Perhaps more important was Young’s vision of Egypt as a beneficiary of wisdom from classical Greece against Champollion’s perspective of Egypt as the origin of classical Antiquity. When you cloak such perspectives in terms of supremacy and inferiority a far more pervasive bias can easily develop. Both men made some wrong turns in their research. Champollion was very lucky with his scholarly training, his connections and his choice of other resources to combine with the Rosetta Stone. It was not just a matter of focusing on the royal names in cartouches, but of gaining insight in the peculiar qualities of hieroglyphs where logograms mostly represented concepts, but also could be used to represent sounds in the rendering of foreign names, such as Ptolemaios and Cleopatra, the two names that finally brought Champollion on the right track to complete and reliable decipherment. With the beautiful and most telling illustrations in view from several museums it becomes clear, too, how much easier it is now to compare such sources. On the website of the British Museum Regulski presents a concise overview of the steps taken by Young and Champollion in their attempts at decipherment.

My curiosity for hieroglyphs grew even more by an episode of the National Geographic tv series Lost treasures of Egypt on the written legacy of Tutanchamon. Deft research of a number of objects connected with this pharaoh led to the suspicion some objects were originally destined for or commissioned by a forgotten Egyptian queen who was almost literally written out of Egyptian history. The most obvious way to do this was tampering with the names in cartouches. In one case the new name was obviously superimposed with a different kind of gold leaf. In some cases there are indications similar attempts were done for Tutanchamon’s legacy, too.

In the third chapter of the catalogue Regulski leads you away from the pharaohs, religion and Egyptian dignitaries to the impact of decipherment for understanding Egypt’s culture and society at large. For example, rather slowly grew any true understanding of Egyptian poetry and its genres, as shown by Richard Bruce Parkinson in his contribution.

‘Rediscovering ancient Egypt’ is the title of the fourth chapter, but it could have been named discovering equally well. Understanding the pharaohs, their reigns and dynasties certainly did not escape from reinterpretation thanks to finally being able to read and understand hieroglyphs, hieratic and demotic script correctly. Bilingualism during the Ptolemaic period comes into view, as are the concept of time and views of the afterlife. Personal life gets attention, too, with subjects such as crime, family, marriage and divorce, satire, love, medicine and magic. Several specialists contributed to this chapter. Here and elsewhere in the catalogue you will find texts in translations as examples of particular source genres.

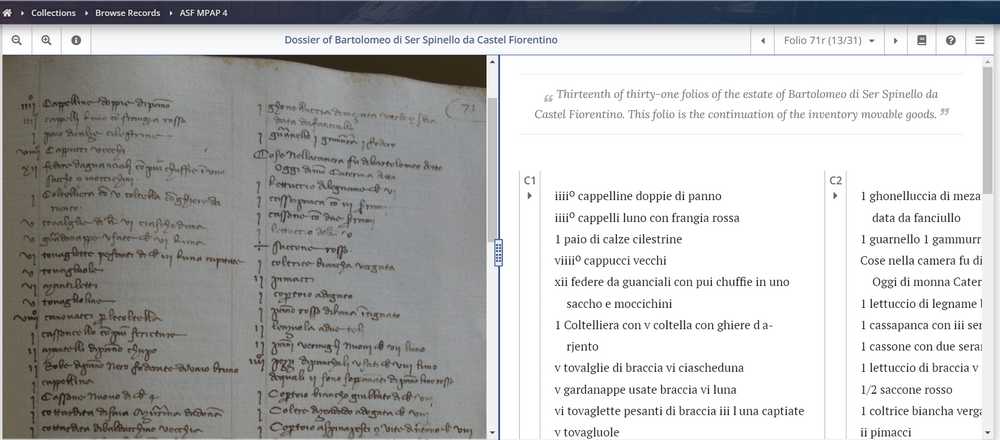

In the short paragraph on crime (pp. 201-204) Ilona Regulski looks at a variety of texts, from royal decrees to court proceedings and private notes. Legal documents could touch upon many subjects, including mortgages and loans. The evidence is preserved in inscriptions and papyri. For the history of daily life and family relations Susanne Beck points to the existence of family archives (pp. 204-209). The footnotes to both paragraphs point you to relevant literature. The great strength here is showing all kinds of documentary evidence and objects.

In the fifth and final chapter new approaches are presented. In the first paragraph Monica Betti and Franziska Naether introduce the Leipzig project for an online version of the Rosetta Stone. Fayza Haikal connects in her short contribution the decipherment of Egyptian scripts and the ongoing efforts of Egyptologists with the search for Egyptian identity. Her point of using knowledge of Arabic poetry to understand aspects of ancient Egyptian poetry is well made. Egypt’s fragmented ancient cultural heritage belongs both to mankind and to living Egyptians who can contribute from inside Egypt – mentally and physically – to research into Egypt’s multi-layered history. This contribution certainly serves its purpose to underline the need to prevent a kind of de vous, chez vous, sans vous in doing research concerning Egypt’s history of more than four millennia.

Matters for reflection

My summaries of the five main chapters of this splendid catalogue do hardly justice to the wealth of information and insights they bring, and to the wonderful accessible writing style of all contributors. The catalogue is a heavy book, but it is hard to put it down and not to read it in one session!

By showing objects now held in various countries and bringing in the assistance of scholars from many corners of the world the catalogue and the exhibition show graphically some of the dilemmas facing current Egyptologists. How must one deal with the fragile remains of antiquities that were taken from Egypt with care or carelessly from their original context? Hardly any untouched mummy has survived nowadays, and the few ones that do show – thanks to modern research methods – things we would not know in any other way. Even when you return objects to Egypt it is not or only seldom possible to restore their original configuration. It is much to the credit of Champollion he pleaded with the Ottoman authorities to impose at least some restrictions on the large-scale industry of providing Europe indiscriminately with Egyptian antiquities. Some most valuable object genres were disregarded at all. Objects were even simply thrown away immediately because Europeans were not interested in them in the early nineteenth century. Of course some scholars and institutions tried to work diligently, but they could not always maintain high standards of conduct. Surely it is important to see that the hunt for contemporary copies of the Rosetta Stone and for similar trilingual or bilingual inscriptions did help to see this object in a wider setting. The catalogue provides you with an overview of these inscriptions in an appendix.

The catalogue with so many qualities misses only a few things. There is no list of contributors and their affiliations. For some lenders of objects their location is specified, but for most institutions this is not mentioned at all. The lenders contribute immensely to the value of this exhibition with their willingness to lend in some cases truly unique objects. The very presence of Egyptian antiquities in so many institutions all over Europe, not only in London or Paris, could hardly have been shown better. Not only the major European countries took part in the race to acquire the supposedly or really most important objects.

Egyptology as a discipline recently received heavy blows by stories about outrageous behaviour around original sources, in particular papyri. This exhibition helps to show the genuine efforts for solid and reliable study of ancient resources which outshine the selfish aims of some people who acted against fundamental principles of good science. Cooperation, comparison and critical understanding are essential for keeping research into classical Antiquity at the level the many subjects and periods included within it fully deserve.

Hieroglyphs. Unlocking ancient Egypt – London, British Museum, 13 October 2022 – 19 February 2023

In this exhibition you do not just have complete and incomplete skeletons. There is general information, there are showcases about individuals whose skeleton in some way can tell us vital information about their life. There is for example attention for the way you can determine gender and age, or detect traces of diseases. Some skeletons, in particular skulls, show the signs of accidents or violence, others are marked by the deadly effects of a disease. Syphilis came to Europe in the early sixteenth century, and its harmful presence is clearly visible once you know the tell-tale symptoms.

In this exhibition you do not just have complete and incomplete skeletons. There is general information, there are showcases about individuals whose skeleton in some way can tell us vital information about their life. There is for example attention for the way you can determine gender and age, or detect traces of diseases. Some skeletons, in particular skulls, show the signs of accidents or violence, others are marked by the deadly effects of a disease. Syphilis came to Europe in the early sixteenth century, and its harmful presence is clearly visible once you know the tell-tale symptoms. Perhaps the most telling part of the exhibition is the room showing the reconstruction of the face of a young girl. She has received the nickname “The Girl with the Ear Clamp” because of the iron clamp used for head caps found in her grave. A lot of techniques and skills are necessary to reach the final result, a startling lifelike face. In order to bring especially young visitors closer to the work done to achieve such results part of the exhibition is a kind of study room with a laboratory. Every Wednesday an archaeologist can give you more explanations about the exhibition and the way archaeologists can now approach human remains. On other days a story-teller takes you back to late medieval Amersfoort, and on Sunday afternoons you can meet the challenge to reconstruct yourself a skeleton.

Perhaps the most telling part of the exhibition is the room showing the reconstruction of the face of a young girl. She has received the nickname “The Girl with the Ear Clamp” because of the iron clamp used for head caps found in her grave. A lot of techniques and skills are necessary to reach the final result, a startling lifelike face. In order to bring especially young visitors closer to the work done to achieve such results part of the exhibition is a kind of study room with a laboratory. Every Wednesday an archaeologist can give you more explanations about the exhibition and the way archaeologists can now approach human remains. On other days a story-teller takes you back to late medieval Amersfoort, and on Sunday afternoons you can meet the challenge to reconstruct yourself a skeleton.