During summer some lighter subjects can come into view, but sometimes you suddenly notice something well worth looking at. In order to protect you from too much centenary celebrations I try to choose every year just a few of them. A new virtual exhibit concerning Hugo Grotius starts with a winning title, Grotius: A life between freedom and oppression has been launched in March 2021 by Leiden University Library on a new platform for its web presentations. One of the most celebrated historic events in the canon of Dutch history is the escape of Hugo Grotius (1583-1645) from castle Loevestein in 1621 where he was imprisoned as the chief follower of the late Johan van Oldenbarnevelt, the statesman who had done so much in creating the blossoming Dutch Republic. An exhibition in Amersfoort on Van Oldenbarnevelt and prince Maurits (Maurice) came into view here a few years ago, and just like in that summer post a particular historical object will figure here. The matters under discussion here are in the end not just light-weight, and thus I finished this post only in autumn.

A canonical figure in Dutch legal history

Before you sigh at the prospect of going on well-trodden paths with me you should know nine students of Leiden University College in The Hague prepared the virtual exhibit in English. Together with their supervisors Hanne Cuyckens and Jacqueline Hylkema they did choose five focal points which are just different enough to make you curious again about Grotius. In the first section, Leiden, the student, he forming years of the child prodigy form the subject. Grotius matriculated at Leiden in 1594 at the age of ten years. For each subject a number of objects are shown, in this case for example the matriculation register, a portrait of Grotius at fifteen, the earliest printed map of Leiden and a portrait of the famous philologist Joseph Justus Scaliger, the best known teacher of Grotius. Grotius started at Leiden with literary studies, not with jurisprudence, freedom indeed for this child prodigy to develop himself in many directions. In 1598 he obtained his doctoral degree in law at Orléans.

In the second section we do not jump at once to his major publications such as Mare Liberum (1609), followed by De iure belli ac pacis (1625) and the Inleidinghe tot de Hollandsche rechtsgeleerdheid (1631). Even a young superstar as Grotius had to immerse himself in at least one subject not just in learned books and contemporary theory, but also in daily practice. Grotius was admitted in 1599 as an advocate to the Hof van Holland, the high court of Holland in The Hague. His position as a lawyer made him for Van Oldenbarnevelt the obvious candidate to set out at length the Dutch position on the freedom of the seas. Already in 1598 Grotius accompanied him on a embassy to France, and afterwards the two men stayed in contact with each other. In this section there is also attention for Grotius’ religious views articulated in his work Ordinum pietas (1613). It put him firmly on the side of the Remonstrant movement favored also by Oldenbarnevelt.

The third section brings you to Grotius’ imprisonment at Loevestein Castle on ground of his religious and political views. The castle is placed on a marvelous strategic spot in the Rhine delta where several of its branches come together. The nearby towns of Gorinchem and Woudrichem are not easily reached. The background with the execution of Oldenbarnevelt in 1619 gets due attention, as are his religious views. You can also look at two letters. When you try to navigate to subsequent items this does not always function correctly. I had expected a link to the online version of the edition of Grotius’ correspondence at the portal of the Huygens Institute in Amsterdam nor to the version at its philological platform Textual Scholarship or to the catalogue at Early Modern Letters Online, but you can look at scans of original letters held at Leiden. The project Circulation of Knowledge and Learned Practices in the 17th-Century Dutch Republic could be added as well.

At Loevestein Grotius was allowed to borrow books from Leiden university library. These books were transported in a large and heavy chest. Hidden in the book chest Grotius could famously escape on March 22, 1621 from castle Loevestein. In 2020 a part of the television series created by the Rijksmuseum on Historisch bewijs (Historical evidence) was devoted to establishing which book chest of three chests held at the Rijksmuseum, Loevestein and Museum Prinsenhof in Delft was probably the original book chest. The chest in Delft has suitable dimensions and a more reliable provenance from the Graswinckel family who was closely connected to the De Groot family in Delft, but no evidence was adduced to confirm its actual use beyond any doubt. Thus the chest is a kind of objet de mémoire connected with an almost mythical heroic story, and the natural point of focus at castle Loevestein, a typical nationalist lieu de mémoire on a beautiful spot at the point where the Waal branch of the Rhine and a branch of the Meuse come together.

In the fourth section of the online exhibit we arrive with Grotius as an exile in Paris. In this town he completed his treatise De iure belli ac pacis. Apart from letters and a map of Paris poetry by Grotius and a poem by Joost van den Vondel come into view here.

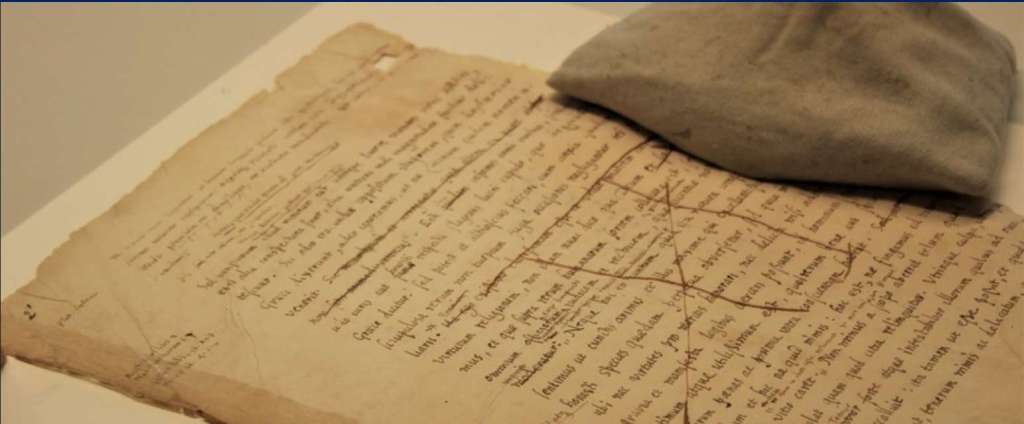

The fifth and final section of the virtual exhibit deals with the major treatise by Grotius on prize law, De iure praedae. The Leiden manuscript BPL 917 is the sole handwritten and even autograph witness to the text of Grotius’ treatise on prize law and booty composed between 1604 and 1609. Only one chapter was published during his life as Mare Liberum (1609). The restoration of this manuscript and the subsequent digitization for the full digital edition published in 2015 are the very heart of this section.

By choosing four actual locations – Leiden, The Hague, Loevestein and Paris – the nine students succeed easily in freeing Grotius from a too narrow view of him as only a figure in Dutch history who became first a victim of religious strife and later on a figure head in the struggle for tolerance. These backgrounds do matter indeed. No doubt some Dutch people will be surprised to find the article on Grotius in the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy and its rich bibliography. He is regarded as the very founder of natural law. Thus there is an entry for Grotius, too, in the database Natural Law 1625-1850, one of the fruits of a research project of the universities at Halle, Erfurt and Bayreuth. By showing not just works by Grotius, and not only his legal works, but also his poems and a treatise on religion, the students show him as a major intellectual in European history. You might with me deplore the lack of further links or an essential bibliography, but there is surely a place for the approach chosen for this virtual exhibit.

Recently Leiden University launched a new platform for its online exhibits. Among the digital collections of Leiden University Library is a section with nearly fifty virtual exhibitions; in some cases only a PDF remains available.

As for creating a Grotius Year the museum Loevestein can readily be pardoned for seeking a way to attract visitors after the corona lockdowns in the Netherlands. The website for the public events around the Grotius commemoration does mention his importance as a lawyer, diplomat and theologian. Themes as the freedom of thought and religious tolerance are vitally relevant in our contemporary world. Showing things have been very different in the past shakes (young) people free from thinking the present has always been there as a a most natural thing.

In earlier posts about Grotius, in particular the one about a rare early edition of De iure beli ac pacis, I provided information about his main legal works concerning the first printed editions, modern editions, translations and digital versions. I would like to point again to the presence of text versions and seventeenth-century or modern translations into Dutch for a number of his works at the portal of the Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren (DBNL). In the DBNL you can find also digital versions of numerous older publications about Grotius, and the entry for his historical works by E.O.G. Haitsma Mulier and G. van der Lem in their work on Early Modern Dutch historiography, Repertorium van geschiedschrijvers in Nederland 1500-1800 (The Hague 1990).

The riches of the Peace Palace Library

The Peace Palace Library (PPL) in The Hague is the natural starting point for any research on Hugo Grotius. Lately this library has put its digital collections on a new separate platform, but for some silly reason the actual URL is not easily found at the website of the PPL, as are alas some other web addresses. A few years ago I wrote here about the Scheldt River collection which now can be found, too, at this new platform. It seems the PPL provides for each collection on this platform a special page with the correct link. However, there is no page or news item for the new platform itself, or maybe it has only to be added to the top bar menu. A platform with eight interesting collections in open access merits a place in the spotlights.

The PPL contributes two collections in open access to LLMC Digital, but no direct links are give on the PPL’s special page for its collections at LLMC Digital. It is only fair to say that finding these collections at the LLMC portal is a feat in itself. So far my attempts to locate them simply failed. Both LLMC Digital and the website of the PPL lack a general search function and a sitemap. The collections at both websites deserve better accessibility. As for the licensed digital collections and also for the databases accessible through the PPL you might contemplate acquiring a library card of this library. For this choice, too, hving a clear overview of digitized materials and their access is most practical.

Grotius figures of course also on the website of the PPL, starting with the chat function called Ask Hugo! The web page on the Grotius Collection tells you about the general background and the famous bibliography by Ter Meulen and Diermanse [J. ter Meulen and P.P.J. Diermanse (eds.), Bibliographie des écrits imprimés de Hugo Grotius (The Hague 1950)] and a more recent catalogue of the PPL’s holdings of works by Grotius. Instead of the direct link to the licensed Grotius Collection Online: Printed Works of Brill only a link to the title in the PPL library catalogue is provided, yet another minor howler. In fact this digital collection contains also numerous works dealing with Old Dutch law, and I would even single it out as a very representative selection of legal books from the Dutch Republic brought most conveniently together. A research guide for Grotius would be a welcome addition to the thirty existing online guides on the website of the Peace Palace Library. A quick search for a nutshell guide to Grotius brought me only to a very concise guide created by the Alexander Campbell King Law Library at the University of Georgia. It is sensible to look at the Grotius pages of Wikipedia in several languages.

Gaining a wider view

I would like to end this post constructively, and not with criticism on defects. Grotius belongs to the group of thinkers students and scholars cannot approach completely straightforward. Often there is abundant scholarly activity, there might be opposing schools and roads of interpretation and across linguistic borders studies can take refreshing turns closed to those staying content with Anglo-American scholarship. Luckily regularly guides are published in the form of essay volumes by an international team of distinguished scholars to bridge such gaps and bring together different views and themes surrounding a major thinker. In September 2021 the Cambridge Companion to Hugo Grotius appeared in print and online, edited by Randall Lesaffer and Janne Nijman. Interestingly this seems to be the first companion volume to Grotius. There is not yet A Very Short Introduction on Grotius from Oxford, presumably exactly because his versatility can hardly be sufficiently shown in a slim volume by a single author. Hopefully different views on Grotius find space in the scholarly journal Grotiana with apart for the printed version some articles published online in open access.

This year’s International Open Access Week will take place from October 25 to 31, 2021. The existence of a number of vital online resources for doing research on Grotius only accessible as licensed resources, most often through the services of libraries, diminishes the chances for those outside the circle of blessed beneficiaries to learn more about Grotius or about other major intellectuals whose thought changed the world forever. Institutions not caring or simply forgetting to provide even links to their own digital collections, be they in open or licensed access, should reflect on their duties and capacities to help both scholars and the general public. Of course in some cases it is a matter of discommunication or worse between for example a library staff, a project leader and the communication officers.

It might seem seducing to bring your collections under the flag of a prestigious publishing company, but if this means closing access to your priceless possessions for most of the world the ultimate blame should be in my view on their original holder. In my view individual scholars, scholarly communities, publishers and research institutions, including university presses, all have their own ongoing responsibility to discuss matters concerning access to scholarly publications. In actual life both institutions with digitized resources and publishers increasingly offer digitized materials both in licensed and in open access, depending on their policies. Hopefully solutions can be found to create and assure wider access whenever possible and feasible for us and future generations interested in the versatile mind of Grotius and the impact of his works through the centuries. Sailing oceans with free, affordable and sustainable access to research resources would be most helpful to achieve this aim.