How do you get the larger picture? Almost with a sigh we often long to see wide vistas, yet at the same time we want to zoom in while looking at a panorama of particular things. In this post I will look both at a repertory of particular sources, medieval and Early Modern city registers, for one country, Germany, and at an attempt to create a similar overview for medieval Europe. Last week I was alerted to the project for Germany, but this week I noticed also the project for a wider overview, and comparing the two projects is the most natural thing to do.

Efforts in Germany

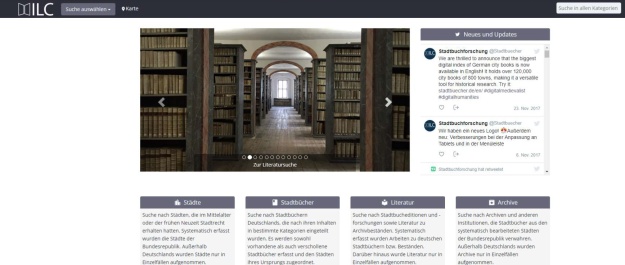

The German project for Deutsche Stadtbücher has a subtitle in Latin, Index Librorum Civitatum. On closer inspection this portal can indeed be viewed in German, English and Latin. As for now the Latin is restricted to the headings of fields and filters. The project is the fruit of cooperation between the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, the history department at the Universität Halle-Wittenberg and the Cologne Center for eHumanities (CCEH). The portal offers four main entrances to search: cities, city registers, literature and archives. The word Archives stands here for holding institutions, not only archives, but also libraries. You can also use a free text field search. It is possible to search only for digitized registers, too. An extra is offered in the expert search mode, and you can also use an interactive map. This map can be used with some filters, but it seems a number of them is not yet active. However, you can go to a second interactive map, the DARIAH-Geobrowser which enables you to filter for periods and series of Stadtbücher. The loading of the results takes some time… On the main map you can select other countries as well. The database has for example currently entries for two Dutch cities, Kampen and Groningen. It is great to have bibliographies for many cities.

City registers or municipal registers is a very broad term. The strength of this project is certainly the creation of eleven categories, ten categories with in four of them attention for those registers most dear to legal historians, court registers, statutes and bylaws, council registers, and the classic registers for acts and charters (cartularies). In the eleventh category you will find everything which does not clearly fit into one of the other categories.

In such a vast project, spanning five centuries, you will find inevitably aspects which are either exhaustively or rather sparingly covered. Project leader Christoph Speer explains at his staff web page that for some Bundesländer he could build on the work of Reinhard Kluge in the former DDR for 450 cities with 70,000 registers, and he refers to a number of publications about the project and German city registers.

Getting a larger view

In 2014 I wrote here about a number of projects for the digitization of Dutch and Flemish city registers, in particular court registers and council deliberations. I discussed projects for Leuven, Liège, and ‘s-Hertogenbosch (Bois-le-Duc). I briefly mentioned some maritime registers at Amsterdam and a project for medieval charters in Tilburg. The Leuven project Itinera Nova is supported by the municipal archive and the Universität Köln. Especially when I looked at the map of the Stadtbücher project in which a center of this university is one of the main partners I wondered for a few moments why Leuven is not mentioned, but it is better to look first of all within the limits set for the Stadtbücher project.

Having within your reach a good and consistent repertory for one country is a fine thing, but often we set out to search for a digital version of one particular source, instead of going first to a relevant repertory. In this context it is perhaps a blessing in disguise that until recently I had not found many digitized medieval municipal registers. I had noticed a French project, Le Petit Thalamus de Montpellier, and a Scottish project, Law in the Aberdeen council registers, 1389-1511. In my 2015 post about portals for medieval history I mentioned briefly the section Paris médiéval at Ménestrel with much attention to legal documents. By the way, similar section at Ménestrel for Lissabon is promising, but has not yet reached this level.

However, very recently I encountered the project Registres des déliberations municipales au Moyen-Âge: La voix des assemblées [REGIDEL], a project concerning cities in Southern France led by the Telemme laboratory at Aix-en-Provence. On November 24, 2017 the symposium Enregistrer les conflits. Pratiques délibératives et scripturales des conseils urbains en temps de crise (XIIIe-XVe siècles, Europe méridionale) [To note conflicts. Practices of deliberation and scriptural practice in urban councils in times of crises, 13th-15th centuries, in Southern Europe] took place. The project blog contains articles about cities such as Turin, Toulouse, Digne and cities in the Emilia-Romagna, in particular for Bologna.

A companion to the REGIDEL project has got its own acronym, MUAR, for Medieval Urban Assembly Records, nothing less than a projected repertory for urban council records in medieval Europe. Like REGIDEL it is currently a blog at the Hypotheses platform. The website aims at becoming an archival and biographical repertory of municipal registers, with a focus on council registers, covering the period from the late twelfth to the early sixteenth century. The interface is in English, French and Italian. Currently there are sections reserved for France, Italy, the Iberian peninsula, the German empire, Britain and Ireland, the Low Countries and other countries. The striking feature here is the wish to classify cities in one region. For a moment I thought the team behind MUAR had fallen into the trap of placing cities in regions which successively were ruled by different rulers, but they mean current regions, for France even the départements.

When I checked the various headings I found partially the same cities as mentioned above for REGIDEL. For Italy you can find Perugia, San Gimignano, Bologna, Reggio Emilia and L’Aquila. Orvieto is the most recent addition, but it has not yet been included in the section for Italy. Most links in this post are internal references. So far Marseille is the only French town in MUAR. All other sections are under construction. For each town a timeline of important events is provided. I decided to check the page for Bologna, a town which figured here in a number of posts, for examples concerning Italian city statutes and municipal ordinances. In one post I portrayed Bologna also as a center of legal history when discussing two projects in Bologna for the digitization of medieval legal manuscripts. In this post I mentioned for the Archivio di Stato di Bologna the digital version of the Estimi di Bologna di 1296-97, records estimating the properties of Bolognese citizens, and the Liber Paradisus, a register about the liberation of nearly six thousand slaves at Bologna in 1257. The MUAR project does mention the critical edition of the Liber Paradisus by F.S. Gatta and G. Plessi, Liber paradisus. Con le riformagioni e gli statuti connessi (Bologna 1956), but not the digital version. The Estimi do not figure at all, nor the digitized Registro grosso (1116-1380) and the Registro nuovo. It is tempting to say the team at MUAR has not yet realized how daunting their objective is, but we can read the notice telling the team is looking for scholars willing to cooperate with them. In view of the German project it seems wise they change from a blog to an online database to enhance search possibilities.

For Italy one can benefit from the Scrineum project of the universities of Pavia and Verona, and more specifically from the Atlante della documentazione comunale italiana (secoli XII-XIV). This Atlante certainly does not cover all Italian towns, but you can find entries for cities such as Genua, Asti, Vercelli, and in particular for Florence. Scrineum provides you with background essays about notaries and libri iurium, and with essays on types of municipal legislation, with text examples from Genua and Florence. Is it safe to assume that there are various groups of historians dealing with legal documents in medieval Italian towns, and that every group has a particular focus? Instead of taking you with me through all kind of resources I had better translate words of Paolo Cammarosano: “As for municipal libri iurium for which there is now a prospect of the creation of a repertory and successively editions, the analysis to be done must reckon with great complexity, different articulations, mixing of matters and outright disorder (…)”, a quote from his article ‘I libri iurium e la memoria storica delle città comunali’, in: Le scritture del Comune. Amministrazione e memoria nelle città dei secoli XII e XIII (Turin 1998) 95-108, online at Rete Medievali Open Archive. The impression of a quick search for literature on libri iurium in the online bibliography of the Regesta Imperii is that of a wide variety of publications focusing on a fairly restricted number of Italian cities.

In the wake of earlier projects

One of the questions to ask for both the German and the French-Italian project is the presence and use of earlier printed repertories and related projects. For the Stadtbücher the team could rely on a project for the Bundesländer in the former DDR as a substantial point of depart. On a European scale fifty years ago a team with a great role at the start for two Dutch scholars, J.F. Niermeyer and C. van de Kieft, edited the first volume of the Elenchus fontium historiae urbanae (Leiden 1967), a project for sources before 1250. The first volume deals with Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Scandinavian countries. The other volumes cover France and Luxemburg (vol. II.1, 1996), Great Britain and Ireland (vol. II.2, 1988), Austria (vol. III.1, 1992) and Hungary (vol. III.2, 1997). On the website of the Commission Internationale pour l’Histoire des villes (CIHV) you can find PDF’s with the preface and overview of the contents of the volumes I and II.2. The Elenchus contains selected texts for the early history of medieval towns. The CHIV also stimulated the creation of country bibliographies.

For Germany it is easy to mention recent and earlier works. Ulrich-Dieter Oppitz published the massive repertory Deutsche Rechtsbücher des Mittelalters (3 vol. in 4 parts, Cologne 1990-1992), in itself a successor to the earlier work by Carl Gustav Homeyer, Die deutsche Rechtsbücher des Mittelalters und ihre handschriften (Berlin 1856; online, Hathi Trust Digital Library; text only, German Wikisource) and his earlier Verzeichnis from 1836 (online, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Munich). Both works deal with legal treatises such as the Sachsenspiegel and Schwabenspiegel, but they look also at the laws of individual cities. A number of Rechtsbücher, influential municipal laws, and Schoffensprüche (decisions of aldermen) figure in the online version of the Repertorium Geschichtsquellen des deutschen Mittelalters under the heading Stadtrecht. I invite you to check also for example at Archivportal-D and the Archives Portal Europe for all kinds of city registers, for they can offer a quick way to relevant registers, too.

Many Dutch rechtsboeken have been edited by member of the Society for Old Dutch Law. Some of the nineteenth-century editions in the first series of editions will not quite stand the proof of modern textual criticism, but at least a large number of them has been digitized at Heidelberg for the Textarchiv accompanying the online version of the Deutsches Rechtswörterbuch. It would be a good thing to create an overview of these texts, the original sources and whenever possible their current digital presence.

To conclude this contribution, proposing the creation of either a national or an European overview of city registers in their various forms is one thing, creating them in a sensible and feasible way implies thorough reflection on many matters before even starting such a project. Overviews of one particular source genre can be most useful, but you cannot lift a source or a genre out of their context completely without impairing in the end historical understanding. This consideration works certainly as a factor which makes scholars rightfully hesitant to cooperate in such projects. The fact that you work with partners from other countries will surely help to widen your horizon and question your assumptions. Let´s wish all courageous scholars who nevertheless join these projects wisdom, good luck and stamina!

A postscript

My view of the German project Stadtbücher is rather positive, but it is right to add at least one comment from Klaus Graf at Archivalia who criticizes the working of the filters and the absence of information for some German regions, in particular Baden-Württemberg. In my opinion the north of Germany is covered massively, for other regions you can clearly wish for more. For Saxony you can benefit from the Gerichtsbücher database for some 22,000 registers concerning voluntary jurisdiction, for example property sales, mortgages, custody and wills.

I spotted in open access the most valuable article on Magdeburger Recht by Heiner Lück in the Handwörterbuch zur deutschen Rechtsgeschichte III (2nd ed., Berlin 2013) col. 1127-1136.