This week news came out about the upcoming payment of interest to Yale University on a perpetual bond issued in 1648 by a Dutch water authority, the Hoogheemraadschap van de Lekdijk Bovendams. Next week its legal successor, the Hoogheemraadschap Stichtse Rijnlanden, will pay the sum of € 136,20 ($ 154), the interest over twelve years. Yale’s Beinecke Library bought the bond in 2003 as a cultural artefact. Not only Bloomberg brings this news item which attracted quickly attention at Twitter, but elsewhere, too, this news has been noticed, for example at the Indrosphere blog by Indrajit Roy Choudhury. On my blog I have devoted some space both to the history of water authorities and the history of shares and stocks, and thus it is logical to write here also about this particular story.

At the website of the Stichtse Rijnlanden it becomes soon clear how this modern water authority is responsible for a much larger area than only the lands adjacent to the Lek, a branch of the Rhine in The Netherlands, for which the old hoogheemraadschap had been founded. The website of the Regionaal Historisch Centrum Rjnstreek en Lopikerwaard, the regional archive at Woerden, offers a concise history of this institution. In 1285 a dam had been placed in the Hollandse IJssel to prevent the water of this river to stream into the Lek near the village of Vreeswijk, now a part of Nieuwegein. After floodings in this region of the diocese Utrecht due to neglect of this dam bishop Jan van Diest published in 1323 an ordinance for its maintenance. The schouwbrief of 1323 was followed by more instructions, in particular by ordinances published on behalf of Charles V in 1537. “Bovendams” means “ahead of the dam”, in this case up to Amerongen, to the east, 33 kilometers. From the dam westwards another water authority came into existence dealing with the Lekdijk Benedendams up to the town of Schoonhoven.

The article in Dutch points to a number of modern studies concerning this water authority. Pride of place should go to an older study by legal historian Marina van Vliet, Het Hoogheemraadschap van de Lekdijk Bovendams: een onderzoek naar de beginselen van het dijkrecht in het Hoogheemraadschap, voornamelijk in de periode 1537-1795 (Assen, 1961). Its long title mentions not only the hoogheemraadschap, but also the term dijkrecht, dyking law. Marijke Donkersloot-de Vrij, a specialist in the field of historical cartography, edited the volume of essays De Stichtse Rijnlanden: geschiedenis van de zuidelijke Utrechtse waterschappen (Utrecht, 1993). The most recent major study, Ad van Bemmel’s De Lekdijk van Amerongen naar Vreeswijk: negen eeuwen bescherming van Utrecht en Holland (Hilversum, 2009) stands out for its colourful photography.

Getting money for major investments

In the media the news about the payment to Yale University was received with some smiles. Does this institution really need this small sum? The Beinecke Library is this year closed for a major renovation and will open only in Fall 2016. Nowadays it is not easy to work on a building site and stay firmly within your budget, and thus even this Dutch payment can be most welcome. Incidentally when you check the collections website of the Beinecke Library it becomes clear that this record (Gen. Mss. File 565) was a gift from the International Center for Finance at the Yale School of Management in 2009, a statement which seems to contradict the assertion at Bloomberg about Yale paying $ 24,000 in 2003 to acquire this bond.

Map of the Lek and the dykes near Honswijk, 1751 – Woerden, RHC Rijnstreek en Lopikerwaard, Lekdijk Bovendams, inv. no. 1154-H

The bilingual website Beursgeschiedenis/Exchange History has a short article showing the 1648 bond is not the oldest surviving one from this hoogheemraadschap, but one from 1624, since 1938 in the possession of the New York Stock Exchange, thus one of the oldest surviving shares worldwide. The 2,5 percent interest yields even today 15 euros. The bonds of 1648 were issued specifically to build a krib, a pier in the Lek near the hamlet of Honswijk, now situated within the municipality Houten. Maintaining such piers and fighting against piers and other structures at the other side of the river kept the hoogheemraadschap busy for centuries. You can download the archival inventory from the website of the RHC Rijnstreek en Lopikerwaard (PDF, 74 MB). Like other Dutch water authorities the hoogheemraadschap was an independent authority which could proceed in court against for instance the counts of Culemborg or the States of Guelders. The website for the history of stock exchange does call to attention the fact that even the counts of Holland and the bishops of Utrecht, in medieval times often deadly enemies, both invested money in the maintenance plans of water authorities.

Light on some details

Some elements in this week’s story need elaboration. You can shake your head in disbelief about a rich university welcoming a payment of just over one hundred dollars, but you might also marvel at the fact of the longevity of institutions vital for the protection of areas threatened by the powers of mighty rivers or seas. Issuing perpetual bonds or rents was not an invention of the Dutch Republic. Medieval rents issued by cities are documented for regions such as Tuscany and Flanders since the thirteenth century. Water authorities could levy taxes to get money, but these taxes were meant to cover the costs of normal maintenance.

To my surprise I found the archival collections of both the water authorities for the Lekdijk Bovendams and Lekdijk Benedendams in the regional archives at Woerden. The archival inventory (finding aid) for the Lekdijk Bovendams had been created in 1980 at the former provincial archive in Utrecht, but a few years ago it was decided to bring a large number of archival collections kept at Het Utrechts Archief to regional archives in the province of Utrecht, and thus you can find currently materials much closer to their origins at Amersfoort, Breukelen, Wijk bij Duurstede and Woerden. Luckily there is a nifty search site for archives in the modern province Utrecht, the Utrechts Archiefnet, but precisely archival records kept at Woerden can only be searched online at its own website. Interestingly the banner of the Utrechts Archiefnet shows a map with at the bottom the Hollandse IJssel and the Lek.

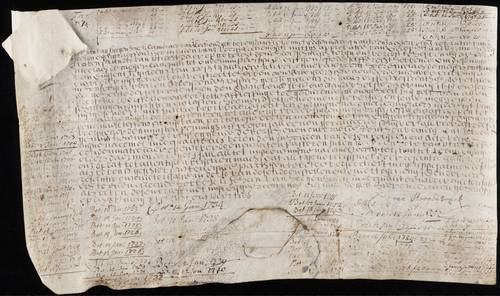

At its collections website the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library shows for the 1648 bond not an image of the original bond but only the modern talon, the leaflet with notes about payments of interest. The Beinecke’s inventory record gives only the immediate provenance of this bond; information about its earlier provenance is absent. The portal Discover Yale Digital Content does list the bond, but precisely for the original document at first no image seemed available. It took me some time to realize that Stichtse Rijnlanden provides with the news item on its website a direct link to the image at the Beinecke Library. It appears a second record (!) for the original bond has been filed as “Lekdijk Bovendams [water board bond]“, with as signature “Uncat. MS Vault File”.

What shall I say here about the double records for the twin items? I suppose we witness the archivists and librarians at work. It is instructive to see at one hand a very detailed indication of subjects using LC Subject Headings, and in the other record just “Business records” and “Certificates”. The more general description gives you the precise dimensions of both items, and the other one has already been included in Yale’s Orbis general library catalog with a cautious remark “In process-material”. It will be a challenge to merge both descriptions into one record. It will be necessary to look at the back of the bond to decipher ownership indications and to confirm the information of the talon: the verso has a note that in 1944 an allonge was issued. The names of former owners are faded or crossed out, and I cannot decipher them quickly, too. “J.J, de Milly” is clear, as is a note about the States of Utrecht from 1652. Dealing with such dorsal notations is one of the goals for which the historical auxiliary sciences have been developed. In fact Yale might consider bringing these items to the Rare Books Room of the Lillian Goldman Law Library, a fitting place for a document with clearly not only a cultural value but also connections to legal, economic and financial history.

No easy answers

How shall we sum up the results of this post? This week’s news item can easily be expanded. At PrefBlog I read a nice rejoinder pointing to a sale in 2000 at Christie’s in New York of yet another payable bond issued by the Lekdijk Bovendams in 1634 which was sold for $ 47,000, twice as much as Yale paid in 2003 for their bond. A genealogist tracing the history of the Van Blanckendael family also came across the 1634 bond and asked the regional archives in Woerden about the perpetual bonds. The RHC Rijnstreek en Lopikerwaard responded in 2011 drily that the archive of the hoogheemraadschap Lekdijk Bovendams contains several obligations from 1624 and 1638, and even from 1595. However, these obligations are not payable anymore, with two cuts in the document they have been cancelled. Not only national governments, cities and commercial companies issued rentebrieven, perpetual bonds, but other authorities, too, benefited in the past from the capital market.

Safeguarding the densely populated Netherlands is still the business of the Dutch waterschappen and hoogheemraadschappen. The one for the Lekdijk is remarkable because it dealt only with the dykes along the Lek and Nederrijn, not with the polders inside Utrecht. It literally pays to have institutions created only for this purpose. Regions afflicted in recent years by river floodings in other countries can tell you about the disastrous impact of neglected dykes. A few years ago the village of Wilnis in my own province Utrecht was hit unexpectedly by a flood caused by a dyke that imploded during hot summer weeks without any rain. The etymology of Wilnis, “wildernis”, wilderness, might wryly serve as a warning of what can become of areas struck by the forces of water running freely.

Last but not least there is the matter of describing, conserving and storing archival records stemming from abroad in orderly fashion. The libraries at Yale University contain an astonishing wealth of materials from all over the world, and most often one can only admire the sheer skills in making them useful and accessible for the scholarly community at large. Last week the Findit search website was launched for sarching digital images at Yale University Library, with a clear notice that seven other digital collections at Yale are to be searched separately. Perhaps the double efforts for the rare still active Dutch bond are a blessing in disguise, even if it shows uncoordinated work. Maybe it is a case of not getting in touch immediately with scholars at Yale who could have saved the librarians and archivists from this situation. Years ago librarians at Munich taught me the fifteen minutes rule for cataloguing: When you cannot figure it out within a quarter of an hour, stop and get help. Getting things right is a hard thing to do. In this case scholars at Yale Law School and its marvellous library would have been most happy and willing to assist, and when necessary they would not hesitate to ask for help from all over the world, in order to bring light and truth true to Yale’s motto Lux et Veritas.

A postscript

David Schorr commented at the blog Environment, Law and History on September 21, 2015, my statements about the unique independent character of Dutch water institutions. In particular irrigation districts, too, tend to be independent institutions. I should have been alarmed by my own use of the notorious word unique! The next thing to question is the way such institutions carried out their jurisdiction. Some Dutch waterschappen had in principle the right to inflict the death penalty for not complying with their ordinances. The blog of David Schorr, Adam Wolkoff and Sarah Mikov is well worth following.

Yale Insights published in 2007 an interview ‘What is a long life worth?’ with William N. Goetzmann and K. Geert Rouwenhorst confirming the purchase of the bond at an auction in 2003. They tell something about other loans and perpetuities. Goetzmann edited the essay volume The origins of value. The financial innovations that created modern capital markets (Oxford, etc., 2005) covering the history of loans from Babylon to modern times, where you can find an article by Goetzmann and Rouwenhorst, ‘Perpetuities in the Stream of History. A Paying Instrument from the Golden Age of Dutch Finance’ (pp. 177-187) dealing in detail with the 1648 bond. The Yale School of Management has created an online exhibit on the history of securities, Origins of Value. You can consult online an interesting bachelor thesis by Mark Hup, Life annuities as a resource of public finance in Holland, 1648-1713. Demand- or supply-driven? (B.A. thesis Economics, University of Utrecht, 2011) (PDF).