While busy with updating the congress calendar of my blog I spotted an announcement about a project at King’s College London, The Making of Charlemagne’s Europe. The website consists of a database containing one thousand early medieval documents, mainly charters. The database is surrounded with a series of useful guides, instructions, a bibliography and a selection of links. The first aim of the database is to create a unified framework to extract socio-economic and prosopographic information from the selected charters. A second aim is stimulating research into these early medieval legal documents themselves.

As a medievalist I have been trained to use all available written evidence to its utmost extent. My first frown when looking at this database was caused by the fact that not all surviving relevant documents, some 4,500 records, have been included here, but perhaps I expect too much. The database is clearly still in a beta phase. The list of charter editions from which documents have been extracted is fairly long. Some collections have been included entirely, for example the charters in the Diplomata Karolinorum series of the Monumenta Germaniae Historica, and from many others at least a few items have been selected. From the edition of the Chartae Latinae Antiquiores all charters between 768 and 814 have been included.

It is probably wise to remember that we are looking in fact at a pilot project, and not to judge it too quickly. If you insist on having more materials immediately at your disposal, you can relish the presence of many online resources indicated in the splendid array of useful links. In this post I will tell you about my first experiences with the website of this project. The decision to create a database for researching Carolingian charters was not an easy choice. The visions behind this project are relevant for many comparable projects. What are the benefits of this project? Does it help to get closer to the legal realities within the Carolingian empire? Does it help us to refine our perceptions of legal history?

Back to basics

Chronicles and charters are the basic materials for doing historical research on subjects from medieval history. In a way the focus on charters of this project brings you back to a familiar playground. When you start to use the database in its simplest way, by browsing charters, you are immediately struck by the multitude of available filters, not only for classic attributes as the transmission date, repository and place names, but for many more determining elements. The filters help you to analyze a corpus of documents in a very structured way and helps to make comparisons possible on a sound base. In particular connections between people and changes in roles – and status – can become much clearer than they were before.

However, I could not help thinking that somehow you will find here only information that has been already labelled by others, but in fact the project team has done a lot more. They insist on making clear the multiple roles and significance of the information in charters. The student guide of the website gives good examples of the tiny differences in very similar charters that should make on think matters anew. In one charter a person is described as the abbot of a monastery, in the next example he is not. The first example mentions the patron saint of a church, in the next charter this information is not present. The examples show also the necessity of distinguishing the location where the charter was created, the place of a donation, places within a certain territory, and unidentified place names. Tucked away in one of the paragraphs of this guide is the very important remark that the database does not give you the actual text and images of charters. Links to digital versions will be added in the coming months. This basic feature, or should one say: basic lack, deserves more emphasis than just an oblique reference.

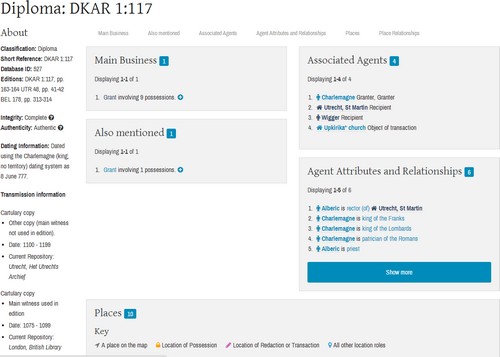

The selection of documents already included in the database was made with an eye to the greatest possible range of places, regions and types of transactions. It should not surprise you that I concluded that even the city of Utrecht, in the Carolingian period decidedly at a distance of the most important places and persons, is present in the database. The charter DKar I:117 (June 8, 777) proved to be a very instructive example. Utrecht is not only the name of the bishop’s see but also of his diocese. The charter was granted at Nijmegen. Several locations in the charter are within the diocese of Utrecht, a number of them at unidentified locations. The recipient of the grant is count Wigger for Alberic, the rector of St. Martin’s at Utrecht. Alberic is a priest. Charlemagne is credited with three qualities: king of the Franks, king of the Lombards, and patrician of the Romans. This is the only example of Utrecht in the database, but it contains enough to place it in a wider context. In 778 Alberic became the bishop of Utrecht. Gaining such personal information is one of the aims of the project.

Seemingly strange is the missing location of the Upkirika, one of the objects granted. The database gives for individual elements the exact wordings, and the location super Dorestad places this church at least clearly in the region surrounding this well-known trade centre south-east of Utrecht. Apart from properties the grant includes also a toll right. The image above does not show the large clickable map where you can see identified locations. To the left of the map is a list of all locations mentioned in a charter. A second overview mentions place relationships. In DKar I:117 Leusden is a place within a smaller territory, in Flettheti. I was somewhat mystified that the database has as a place entry Utrecht, territory (Flehiti), and not inversely Flehite, with as description “territory in Utrecht”. The procedures behind place relationships are discussed in an interesting contribution on the project website.

The list of useful links at The Making gives for the Netherlands only the online version of the registers of the counts of Holland and Hainaut between 1299 and 1345 and a link to the online list of medieval cartularies and modern editions at TELMA. In the list of charter sources only the Oorkondenboek van Noord-Brabant tot 1312 (ONB) has been included. However, a number of Dutch and Belgian charter editions (oorkondenboeken) is even available online. The Oorkondenboek van het Sticht Utrecht tot 1301 (OSU) has been digitized by the Huygens Institute, as are the ONB – in a partnership with a foundation for the history of Brabant – and the Oorkondenboek van Holland en Zeeland tot 1299 (ONH). The portal Cartago leads you to charter editions for Friesland, Groningen and the German region Ostfriesland. Medieval charters from Belgium will become available online in 2015 within a project called Sources from the Medieval Low Countries, supported by the Belgian Royal Historical Commission. You can use a cd-rom with the Belgian Thesaurus diplomaticus from Brepols. The URL for the Diplomata Belgica does not yet function. Among the Scandinavian diplomataria the Svenskt Diplomatarium is not mentioned, perhaps because the oldest document in it dates from 817, just outside the period under consideration here. On that ground you could also exclude the Diplomatarium Norvegicum which starts in 1050. I am sure this and similar information will be swiftly added or corrected.

Apart from browsing for charters you can browse for agents and places with a similar wide range of filters. Conceptually the very act of creating of a charter is seen as amounting to a fact, called a factoid, with connections to places and peoples, and probably changing them, too. It is very advisable to read the contributions at the website about the choice to create a database instead of opting for the use of “mark-up” texts.

By the way, choosing Utrecht as an example in this post is not a random act. The Utrecht Centre for Medieval Studies has a fine tradition of research into many subjects of the Carolingian period, including legal history, for example the history of penitentials, see Rob Meens, Penance in medieval Europe, 600-1200 (Cambridge, etc., 2014). The latest project Charlemagne’s Backyard looks at the rural history of the Low Countries in the Carolingian period, combining both written and archeological evidence.

A first impression

Are there similar projects where you can find more? The Making of Charlemagne’s Europe does use data from the Nomen et Gens project at Tübingen with prosopographical and onomastic information from the eight century. CharteX deals with charters from the twelfth to the sixteenth century. The use of maps in the project of King’s College London reminded me of the interactive maps of Regnum Francorum Online, a project of Johan Åhlfeldt. It is certainly wise to use this geographical information to check and corroborate search results in the KCL’s project. It is surely possible to give more examples of digital projects which support your research into Carolingian legal documents, such as the Carolingian Canon Law Project led by Abigail Firey (University of Kentucky), and the Bibliotheca legum (Karl Ubl, Universität Köln) with the socalled Völkerrechte.

It is a silly joke but The Making of Charlemagne’s Europe is still a bit in the making. The rebuttal by the project team to this remark is really justifiable: They assemble the very evidence to help you to question the truth behind the assumption that Charlemagne and his successors aimed at creating something like a European presence. When you combine the data contained in their database with printed and online editions of Carolingian charters, and preferably also with any other kind of legal documents from this period, you will be able to get a much more detailed view of Carolingian society, the networks and relations. The Making is not the definitive answer to research questions, but it does deserve inclusion in your digital toolkit when doing Carolingian legal history. One of its great merits is its refined conceptual framework for studying and analyzing medieval charters. Even without a working database the approach to Carolingian charters is worth close study. 2015 is just a few days old, there is enough time this year to look at legal history with new eyes!