The Heksenwaag, Oudewater – image Geschiedkundige Vereniging Oudewater, http://www.geschiedkundigeverenigingoudewater.nl/

This month the walking historian marches again! In July I visited the tiny town of Oudewater, a city in the southwest corner of the province Utrecht. In the beautiful old city of Oudewater the historic Heksenwaag, the Witches Weigh-House is not to be missed. However, in fact I did almost overlook it due to the fact that in my memory the building was much larger. As a kid I had visited the Heksenwaag, and I even received the certificate stating my weight was normal. Coming back to this town things seemed different, but the degree of change was really surprisingly low. Afterwards I could not help questioning what I had seen and doubting my assumptions and conclusions. Moreover, the Heksenwaag is not just a building which any tourist has to visit, but it is a veritable Dutch lieu de mémoire. It links directly to the history of European witchcraft and the ways law and justice dealt with this phenomenon. The results are interesting enough to include in this post which has as its second focus the perception of Oudewater’s history.

Hard facts and shallow assumptions

In De canon van Nederland, “The canon of Dutch history”, the Heksenwaag at Oudewater is connected to emperor Charles V. He is said to have granted Oudewater in 1545 a privilege to weigh persons suspected of witchcraft and to issue certificates of normal weight. The vogue for historic canons in the Netherland has led to several regional canons. In the canon for the southwest corner of Utrecht the story of the Heksenwaag is strongly qualified. Legend had preserved a tale of Charles V doubting in 1545 a witch trial at Polsbroek where a woman had been weighed and found too light. He ordered a second weighing at Oudewater, showing her to have a weight of 100 pounds, which saved her, As a sign of gratitude for the correctness of the staff at the weigh-house he granted the privilege. However, there was no weigh-house at all in the village of Polsbroek. The scene of the false weighing could have been the town of IJsselstein. There is no trace of any privilege from 1545 for Oudewater.

Where do we find sources on the medieval and Early Modern history of Oudewater? This very question does bring you quickly to sources touching upon legal history. Joost Cox published in 2005 for the Foundation for the History of Old Dutch Law a repertory of Dutch medieval city charters with grants of specific rights, bylaws and ordinances, the Repertorium van de stadsrechten in Nederland (The Hague 2005). At the accompanying website you will find only lists of cities and dates. With some caution Cox traces such a charter for Oudewater said to be given in 1257 by Hendrik I of Vianden, bishop of Utrecht from 1249 to 1267 (Cox, p. 190). The Institute for Dutch History has recently digitized the major modern editions of medieval charters for the county of Holland and the diocese of Utrecht. The Oorkondenboek van het Sticht Utrecht tot 1301, S.Muller Fz. et alii (eds.) (5 vol., Utrecht 1920-‘s-Gravenhage 1959) does contain an item for this charter (OSU III, 1428) which shows a short reference in a chronicle as the ultimate source of all later information. The chronicle places the gift of a city charter in 1257. Some later authors misread the chronicle and placed it in the year 1265. Nevertheless the city of Oudewater prepares the celebration of 750 years Oudewater in 2015. A celebration in 2007 would have been equally justifiable…

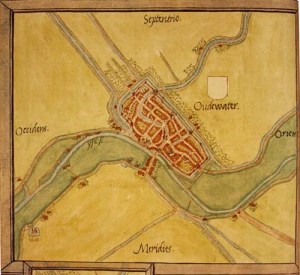

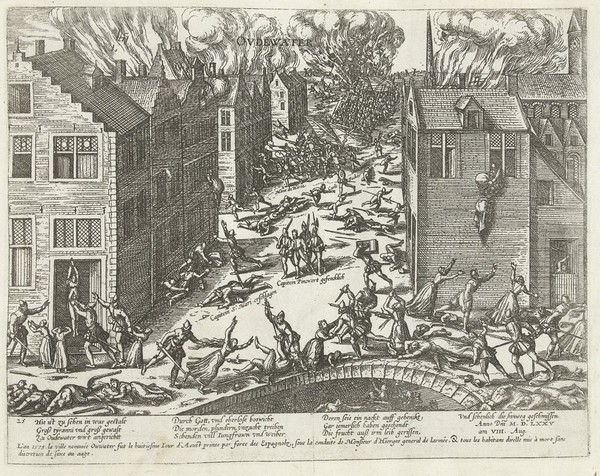

The remarkable insistence on some presumed historical facts in the history of Oudewater comes in a different perspective when looking at a number of events that most certainly determined its history. During a war between the bishop of Utrecht and the count of Holland Oudewater was severely damaged during a siege in 1349 (see for example the Divisiekroniek of Cornelius Aurelius (Leiden 1517) fol. 212 recto). Oudewater held a strategic position a the junction of the rivers Linschoten and Hollandse IJssel. In 1281 the bishop of Utrecht pledged Oudewater and some other possessions for 6000 livres tournois to the counts of Holland (OHZ IV, 1938 (1281 January 24)). The bishops of Utrecht never were able to repay this sum, and thus Oudewater remained until 1970 a town in Holland. On June 19, 1572, Oudewater was captured by Adriaen van Zwieten, and it became one of the earliest cities in Holland to side with William of Orange. On July 19, 1572 Oudewater participated with sixteen other cities in the first independent session of the States of Holland at Dordrecht, a landmark in the long struggle of the Low Countries with Spain, the Eighty Years War that lasted until the Westphalian Peace (1648).

Engraving by Frans Hogenberg of the atrocities in Oudewater, 1575 – Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, collectie Historieplaten Frederik Muller – see http://www.geheugenvannederland.nl/

The change of sides in June 1572 and the presence of Oudewater at the historic session in Dordrecht a month later had undoubtedly been noted by the Spanish authorities in the Low Countries. The locations of Dutch cities had been chartered quite recently by Jacob van Deventer, the cartographer charged by the Spanish king Philipp II with a large-scale cartographical project. The surviving maps have been digitized in the Biblioteca Digital Hispánica. When Spanish forces approached Oudewater in August 1575, an ultimatum was sent urging the city council to surrender. By sheer misfortune this ultimatum was not properly understood. On August 7, 1575 the city was set to fire and many citizens were ruthlessly murdered. Only the church of St. Michael’s and a monastery did escape the devastations. These events clearly affected also the survival of historical records. With much support from nearby cities such as Gouda Oudewater was quickly rebuilt. The results of this building campaign are still visible in the center of the city which looks indeed rather unified if you look closely enough. The destruction of the original buildings, and presumably also of many historic records, explains the tendency to stick to some acclaimed stories and events. Archival records concerning Oudewater can in particular be found at the Regionaal Historisch Centrum Rijnstreek in Woerden and at Het Utrechts Archief in Utrecht. The survival of written records plays a role, too, in the project of Sophie Oosterwijk and Charlotte Dikken on the floor slabs of St. Michael’s at Oudewater.

Of witches, historians and tourists…

Perhaps I had start here better with stating my relative unfamiliarity with the history of witchcraft. As a historian I have kept this subject on purpose on a safe distance, but in the end there is no escape from it, in particular because the subject of persecution and trials is not far away from the main territories of legal historians.

Debunking some part of history is nothing special, nor is it my aim to expose any mystification. Others have done this thoroughly for the Witches Weigh-House. Under the pseudonym Casimir K. Visser the exiled German journalist and historian Kurt Baschwitz (1886-1968) published the study Van de heksenwaag te Oudewater en andere te weinig bekende zaken (Lochem, [1941]; online at the Dutch Royal Library). Baschwitz pointed to an inspection in 1547 of the weights used at the weigh-house, a fact adduced by earlier historians, but actually a normal procedure which says nothing about any special use. He notes the careful avoidance in the certificates of any reference to a belief in witches, witchcraft, sorcery and similar things. Baschwitz referred to Johannes Wier (around 1515-1588), the famous Dutch physician who fought against superstitions, Wier did not mention Oudewater at all in his 1563 treatise De praestigiis daemonum nor in his De lamiis (1577). Both books were often reprinted and appeared in translations. Balthasar Bekker (1634-1698), too, did not credit Oudewater with any special role in his famous book De betoverde weereld (1691). Baschwitz published in 1963 his great study Hexen und Hexenprozesse. Die Geschichte eines Massenwahns und seiner Bekämpfung (Munich 1963). Hans de Waardt reviewed the historiography concerning Oudewater and witches in his article ‘Oudewater. Ein Hexenwaage wird gewogen – oder: Die Zerstörung einer historischen Mythe’, Westfälische Zeitschrift 144 (1994) 249-263 (online (PDF) at the Internet Portal Westfälische Geschichte). De Waardt wrote his Ph.D. thesis on sorcery and society in the province of Holland, Toverij en samenleving in Holland, 1500-1800 (diss. Rotterdam; The Hague 1991).

For the study of Johannes Wier Dutch readers can benefit from the marvellous recent study by Vera Hoorens, Een ketterse arts voor de heksen : Jan Wier (1515-1588) [A heretic physician for the witches, Jan Wier (1515-1588)] (Amsterdam 2011). On Balthasar Bekker Johanna Maria Nooijen published in 2009 “Unserm grossen Bekker ein Denkmal”? : Balthasar Bekkers ‘Betoverde Weereld’ in den deutschen Landen zwischen Orthodoxie und Aufklärung (Münster 2009).

It might be useful to mention the special website of the main Dutch historical journal Bijdragen en Mededelingen betreffende de Geschiedenis der Nederlanden / Low Countries Historical Review where you can search online in the issues from 1970 to 2012. As for searching literature for European history you will no doubt gain information and insights at the portal European Historical Bibliographies maintained by the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. A number of current historical bibliographies presented at this portal can be consulted online. For the history of the city and province of Utrecht you can use the online bibliography at SABINE which in a number of cases provides also links to digital versions of articles and books.

Researching the history of witchcraft

When it comes to studying the history of witches and witchcraft I must confess to start at almost zero. It is years ago that I read a monographic study on witchcraft, and this particular study, Lène Dresen-Coenders, Het verbond van heks en duivel : een waandenkbeeld aan het begin van de moderne tijd als symptoom van een veranderende situatie van de vrouw en als middel tot hervorming der zeden [The pact of witch and devil: an Early Modern fallacy as a symptom of a changing situation for women and as a means to reform morals] (diss. Nijmegen; Baarn 1983) did not convince me at all. Perhaps I was simply wrong in choosing to read this book with its overlong title and its hypotheses which still seem to me farfetched. In fact I kept away from a whole group of Dutch historians doing maatschappijgeschiedenis, “history of society” who favored studies of minorities to detect changes in mentality. Any exclusive focus still makes me frown, but the history of mentalities and cultural history in general is of course fascinating and most valuable.

If I was to start nowadays doing research on this theme I would look first at such fine guides as the section on Hexenforschung at the German history portal Historicum.net. Klaus Graf is the moderator of a useful mailing list on witchcraft research. You can also point to a succinct thematic bibliography provided in Dresden, the Dresdener Auswahlbibliographie zum Hexenforschung, which unfortunately has not been updated since 2004. In Tübingen the Arbeitskreis interdisziplinärer Hexenforschung sets an example of bringing several disciplines together. Unfortunately Jonathan Durrants’ online Witchcraft Bibliography was not available when writing this post. Older literature up to the end of the twentieth century can be found for example in a bibliography preserved at a website of the University of Texas. For Flanders Jos Monballyu (Kortrijk) has created a fine online bibliography and a selection of relevant sources concerning witch trials. He has written many studies about witches and traced many criminal sentences concerning them in Flemish archives. The Cornell University Witchcraft Collection is most useful with its bibliography and digital library.

In American history the Salem Witch Trials (1692) offer a fascinating window on early American society. You can find many documents online, in particular at the Salem Witch Trials Documentary Archive and Transcription Project (University of Virginia), at Douglas Linder’s Famous Trials website and at a portal dedicated to the events in 1692 with a digital collection of books and archival records. The perceptions of behavior and the attempts at dealing with such behavior in courts of justice, not to forget the changing perceptions of justice, are among the elements which make the persecution of witches, witchcraft and sorcery interesting for legal historians.

Of course these examples can be multiplied, but this would far exceed the boundaries of a blog post. Here I have sketched only the outlines of things worth exploring further. I called Oudewater a Dutch lieu de mémoire. In the book series Plaatsen van herinnering sofar five volumes have appeared since 2005 which follow for my country – albeit somewhat belated – the example of Pierre Nora’s seminal Les lieux de mémoire (3 vol., Paris 1984-1992). This interest in historical places and the ways events are remembered at particular places help us to remember history and legal history, too, happened to people in particular times and places, and not just somewhere as a part of a supposed or real historical process. Even a small building in a dreamlike preserved old town can relate to larger events. The scenic old streets of Oudewater was the scene of some very real events, but they are the background, too, for a very stubborn tradition of perceived history. The living memory and the construction or even invention of (parts of) history related to a particular place tell us the fascinating history of the uses of history, changes in perceptions and the construction of identity in time and space.

One of the things that make me uneasy in writing about witchcraft is the sheer proliferation of literature on this subject. Many scientific disciplines occupy themselves with sorcery and witchcraft and its history. It is very easy to miss a whole range of interpretations stemming from a particular corner or country. The road of using bibliographies is long. Sometimes it seems attractive to take a shortcut which in the long run does not bring you much further. Legal history should pay due attention to colored perceptions and distortions of historical facts and events in order to keep an open eye for its own pitfalls, shortcomings and blind corners.